Garlon Glover's story revolves around his wife, Micheline Glover.

Micheline wrote her own bio, which Garlon kindly provided. The following

is her story.

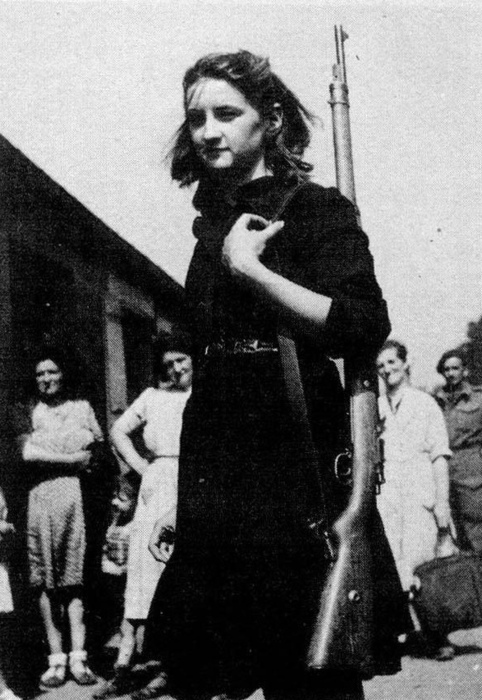

Introduction: A French war bride who followed her husband to the United

States, Micheline was awarded a citation after the war from Gen. Dwight

D. Eisenhower for her help in rescuing Allied airmen from the Nazis. She

was born in Paris on Nov. 29, 1923, to Lambert Blum-Picard and Josephine

Berthet. She was raised in France and learned to speak English at summer

school in English boarding schools.

While many French chose to remain neutral during the German Occupation

or actively collaborate with the Nazis, Micheline was among the minority

who chose to fight. “She really believed in her country, and it was the

right thing to do,” said her daughter, Christiane Glover of Ossining,

New York.

Her family moved to Montlucon in the central section of France, and

Micheline soon joined a Resistance cell run by Pierre Kaan, a Jewish

philosophy professor who was later killed in a Nazi death camp. As a

pretty 18-year-old woman, Micheline made an ideal courier for the

Resistance, taking trains all over southern France with messages for the

underground strapped to her back. She always chose to travel in

compartments where German soldiers were seated.

Towards the end of the war Micheline joined a combat unit of the

Resistance as a medic. After the Allied liberation of France began in

1944, she took part in the fighting that drove the Germans from her

village. She finished the war as an interpreter and liaison officer with

Canadian and American military units and was awarded a Croix de Guerre

from the French government.

During a Red Cross dance in Paris, Glover met her future husband, Garlan

Glover, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. “She was a very

good-looking woman. I saw her dancing with someone else, and I cut in,”

Garlan Glover said of his wife.

Though he was due to be decommissioned and shipped back to the United

States in a matter of days, Garlan Glover decided to stay in Paris as a

civilian. The two were married in Paris in September, 1946. Gen Charles

de Gaulle, the future president of France, sent them a handwritten note

of congratulations.

They moved to White Plaines, New York, in 1955.

The following is Micheline's story in her own words.

- - - - -

I am one of quite a few French women in the United States who lived in

occupied France through World War 2. I have many French friends, each of

whom has had a different experience according to circumstances; a

relative prisoner of war in Germany, a home being destroyed by bombing

forcing them to move far away, a relative having fled to join the French

free forces, another having to hide because of being Jewish, or because

they fought in the Underground.

I am one of quite a few French women in the United States who lived in

occupied France through World War 2. I have many French friends, each of

whom has had a different experience according to circumstances; a

relative prisoner of war in Germany, a home being destroyed by bombing

forcing them to move far away, a relative having fled to join the French

free forces, another having to hide because of being Jewish, or because

they fought in the Underground.

In my story I will go back before the war. After the 1st World War, the

League of Nations decided that the Saar Territory, which is spread along

the French/German border, would be under French control until 1935. At

the time, its inhabitants would vote to become French or German. In 1930

my father was appointed by the French as a high official in Saarebruck,

the capitol of the Saar. So all of my family moved there. Already the

Nazis had started their propaganda, marches, and riots in the Saar. A

French school had been provided for the French children. Everyday a bus

would pick up the children. Actually the bus was a military truck, well

covered, as the German children would regularly throw stones at the

vehicle. So at the age of six, I had my first experience of German

Nazis. No use telling you then that the vote in the Plebicite in 1935

went for becoming full fledged German again.

So back to Paris my family went. My father had been notified that the

Germans had made a Black List of all the high French officials who had

run the Saar.

Nineteen Thirty-Nine came with all the threats of war. As a precaution,

we moved to the southwest of France, where we were when the war broke

out. My father, who was part of the French government, had stayed in

Paris.

France was being invaded by Germany. Thousands of refugees were fleeing

through the country. After a while, after the French government had fled

to Bordeaux, and De Gaulle gone to England, we decided to go back to our

home in Paris. Because of many destroyed or damaged areas, we made a big

detour, staying a day in Marseille where we were bombed by the Italians

who had then decided to declare war on France.

Back in Paris, life started again with all the restrictions the Germans

made. At the time I was sixteen. My first gesture of rebellion was to

take part in the students’ march to the Arc of Triumph on November 11th,

Armistice Day, which the Germans had prohibited. We were thousands there

and the Germans were not able to control us, so they started to machine

gun us. From that time on, German soldiers were attacked in the subway,

in the streets at night, and repressions, arrests and strict regulations

were in effect.

My father decided that it was not safe for him anymore and for us to

move to the “Unoccupied Zone” of France. There was no way to get a

border crossing permit; so each of us, father, mother, my sister, my

brother, and I, passed that border line separately, one in the trunk of

a car, another with the crossing permit of a friend, in a train, et

cetera.

We settled in the city of Montlucon in about the middle of France, not

too far from Clermont Ferrand or Vichy. My father had an executive job

with a half private, half government, company and we three kids were put

in school. The only high school in Montlucon was for boys only. So I was

the only girl in a class of forty. My younger sister and brother were

put in a religious school. I soon discovered that in my English class I

was very much ahead of the others, mostly because as a child I had spent

summers in England in a boarding school. Therefore, in order to advance

my English studies, I asked my English teacher to give me private

lessons. Eventually I discovered his political and patriotic views, and

he mine. I asked him if there was any way I could do something to help

our cause. After a while, the answer was yes. Thus I found out he

belonged to the Resistance Movement, a network called “Liberation.” He

became my “Chief.” The group was very well organized. Any individual

knew only two or three others, for security reasons. The head of our

group was a philosophy teacher, a well known personality, who eventually

was caught by the Gestapo and sent to his death in a concentration camp.

I became a courier receiving important messages from him to take to

other cities and bringing back others. Very soon I was traveling to such

cities as Clermont-Ferrand, Vichy, Moulins, Lyons, et cetera. I traveled

mostly by train. It was best to pick a compartment where German soldiers

sat as the German military police checked all passengers frequently.

Meanwhile, my father decided that he must leave France and he wished to

join De Gaulle’s government in London. Through my connections, he was

able to get the right contact and the English sent a plane to pick him

up. He made it alright. My mother was told that the best answer she

could give to the Gestapo would be to say that she did not know where he

was, his having left her for another woman. In large part, I became the

head of the family. I had to decide to quit school as I was traveling

all the time.

Often I derouted because the railroad tracks had been blown up by a

Maquis, or there was an early curfew in the city I was in and I could

not risk being picked up because of the precious papers I was carrying

strapped to my body. I spent a lot of time dodging German patrols late

at night, sleeping in railroad stations or in the armchairs of the

apartment of my contact. I would meet my correspondent in very different

places, for instance a café, the German military cemetery in Clermont, a

church, or walking along a river, supposedly with an amorous boyfriend.

A big surprise one day was to ring at the apartment of an old lady one

evening in Lyon, and after giving the password, walking in and finding

six or eight men armed to the teeth with machine guns and all, some of

them asleep on the floor, others discussing quietly their next move.

Another time I met a young man, about my own age, in a café frequented

mostly by German soldiers. We sat down in the back of the place. He was

carrying a large package, packed in badly torn paper. After exchanging

our envelopes, he whispered to me, “Help me refold this rubber raft.” It

was obviously an item dropped by plane to the Partisans. We rewrapped it

in this place full of German soldiers.

Another time I was sent to a remote, small village by train. The train

was an old, slow one, just one big car with a stove in the middle that

the conductor fed every so often (that made me think of an American

Western movie). I had never seen a French train like that before. When I

got off the train and stepped on to the main street, I saw several

civilian men carrying guns and machine guns everywhere I looked. They

regarded me very suspiciously as I did them. I thought they could be the

Milice, which was the French equivalent of the Gestapo, a bunch of

hoodlums and jailbirds drawn to that business by money. I finally, very

cautiously, met the man to whom I relinquished the message and found

that it was a Maquis which invaded the village (no Germans there) for

food supplies.

At one time, our home (actually the garage) became a warehouse for

clothing for the Maquis. My mother did her share; she was asked by my

superior if she could hide, feed and clothe a Canadian O.S.S. who needed

shelter for two nights. A few days after that the Americans bombed the

huge Dunlop factory in Montlucon which had been taken over by the

Germans and was working full-time for the German army. I was out of town

when this occurred but on getting back the day after, was able to

provide the Allies with lots of pictures of the destroyed factory.

Another time, my Chief called me and asked me to take over care of two

young American flyers who had been shot down. I found clothes for them,

sheltered them in different villages, and moved them to different areas.

All this movement had to be done on bicycles and these two had not

ridden a bicycle since their early youth. They also looked so American

that I was very glad we did not meet any German patrols on our way.

After many days, another member of the Resistance took them on, on the

way to Spain. Unfortunately, I found out later in a letter written by

his parents to me here in the states that one of them was killed in a

skirmish with the Germans.

Also, some friends of mine from Paris contacted me looking for a way to

reach a Maquis, and I was able to help them. I was also able to forge a

few false identity cards. Speaking of identity cards, this is what

happened to me. Once on a mission to a certain town, I took the train as

usual, but the train was suddenly stopped and derouted, as the

Resistance had blown up the tracks. We came to a halt in a small town

and to our dismay, the platform was covered with German soldiers. We

were ordered to get off the train, get in line one by one and present

our identity cards to the German officer in charge.

As I got closer to him, I realized I had forgotten my I.D. A French

identity card shows a picture and fingerprints. The only thing I had was

a Red Cross card which had none of that. Of course, the officer saw that

at once and he ordered me to stand aside. The line of passengers was

dwindling down and I was still the only one put aside. I could not risk

being interrogated and searched. As the last “checked” passenger joined

the line going back to the train, I started walking behind him,

expecting a loud halt or a shot. These few minutes were the longest of

my life. My normal breath came back only after the train started to

leave.

I must confess how I almost took part in a burglary. My Chief told me

one day, “We are going to raid the big country home of a well known

collaborator who has accumulated provisions of food for the Germans.”

The Maquis close to our town needs the food. Do you want to be part of

our raiding group? Of course, I said yes, but I found out that the

collaborator was the father of a young man who was in the high school I

had attended, in fact, in the same class so he knew me well, of course.

So I decided to wear a mask in order not to be recognized.

The raid was to take place at night. I started making a mask but

unfortunately, my mother walked into the room while I was working on it

and I had to confess. She was very upset, talked to my Chief, and I was

left out, very unhappy. I returned to my usual missions. A few months

after that, word came from London that I had to stay low for a while. I

did, but quickly resumed my activities.

In four years, we only heard once from my father who was in De Gaulle’s

government. When he followed the General to Algiers, he managed to get a

letter to one of my cousins in Switzerland, who brought it to the border

where my mother picked it up. Meanwhile in Paris, three of my cousins

had been arrested by the Germans. A German official had been killed in a

street, so the Germans picked up fifty French in an area of one block an

deported them. My cousins did not even reach a concentration camp but

died in the train.

Then the moment we were all waiting for finally came. On the B.B.C. came

the secret message for our area. The Allies were going to land. It was

also the signal for the resistance to start the open fighting. The

middle of France where we were was not going to be freed by the Allies

from their landings in Normandy or the south of France. So it was up to

us, all the different Maquis, to start the fights in our areas.

My group, an intelligence outfit, was not involved in actual combat.

Therefore, I decided to try to join the nearest Maquis which was an

F.T.P Maquis, the Partisans, mostly made up of men who had fought in the

Civil War in Spain, that is to say of Communist tendencies. I didn’t

care. They were going to fight so I applied right away.

“Sorry,” said the Chief of the Partisans, a Major, “We do not accept

women. Only a nurse can apply.” As I had a diploma from the Red Cross as

a paramedic, I was accepted as a nurse but was informed that the Germans

didn’t recognize the Partisans (F.T.P.) as legitimate fighters so if I

was taken prisoner, I would be automatically shot.

I was armed with a rifle, revolver, and hand grenades. I joined the

Battalion which consisted of 300 men and two nurses. Our fighting

started around the town of Montlucon where I had left my family and we

soon took the town. In the Army barracks which had been occupied by the

German troops, we found the basement rooms spotted with blood and other

human debris from the hostages the Germans had tortured. Our reward was

the joy of the crowds as we drove through the town after the running

Germans – we kept after the Germans all the way.

Then came the day. A message came for me from my mother. “Your father is

back in Paris with General De Gaulle, we will be escorted back to Paris

and he is asking you to come back.” I was demobilized, said goodbye to

my companions who kept on their advance to the East of France until they

were incorporated into the free French forces or F.F.I., and went on

into Germany.

I reached Paris, still in my Partisan uniform, rucksack on my back.

There must have been a shocked receptionist when I walked into the

exclusive Claridge Hotel which had been requisitioned for the French

government executives and families. Our family was back together again.

But the war was still on. I joined an outfit made up exclusively of

women who had been in the Resistance and became a liaison officer with

the Canadians. I worked for a while at the French Army Intelligence

Headquarters in Paris. Then I was sent to the north east of France where

the fighting was still going on. When the Allies finally crossed the

border into Germany, I served as liaison officer between the Prefect of

Moselle and the Americans.

Back to Paris where I didn’t stay very long as I was sent back to

Lorraine to a military intelligence outfit. There, one day, I got a ride

into Sarrebruck, the capital of the Saar, where as a child I had been

stoned by the Germans. The city was still burning. I could not even find

the street on which we lived.

Then the D.G.E.R., the equivalent of G2, sent a group of officers,

myself included, to the British Occupied Zone of Germany, but that was a

very short stay. I went back to Paris, working with the Canadians again

until our women’s outfit was disbanded in June 1946. I left very good

friends with whom I still have contact. I have memories I will never

forget. I live in America now with an American husband, six children and

six grandchildren, but France is still my home.

- - - - -

Micheline Glover, onetime French resistance fighter, died in 1999.

Micheline and Garlon were truly part of America's greatest generation.

We all owe them deep gratitude for the freedoms we hold today.