Continued from the September 2012 Home Page. To go to an archived version of

that page click here:

November 2012 Home Page

Archive. To return to this

month's actual Home Page click on the Signal Corps

orange Home Page menu item in

the upper left corner of this page.

continuing...

Having said all of this, it must be recognized that the

Vietnamese central government’s approach to internal

policies that affect its ability to maintain regime security

within the country is different than what it will do and say

as it looks to broaden relations with external countries.

That is, how it treats its people on the subject of regime

security is one thing. How it treats countries like America

on this same topic (i.e. countries that may present some

risk to it) is another. Considering of course that this is

what interests us here, it’s necessary for us to understand

what Vietnam stands to gain and lose if we are to craft a

policy on our own part to interface more closely with them,

without making them think that we want to tell them how to

run their country.

Recognizing the duality of the need to interface and trade

with democratized western countries while avoiding their

attempts to influence Vietnam’s form of government, Vietnam

is conflicted. On one hand, closer relations with the US

will bring tangible economic and strategic benefits to the

country. As an example, it will get better access to western

capital, markets and technologies, while enjoying a better

means of balancing itself against the growing power of

China… thus creating a more peaceful and safe place for it

in the world. On the other, party officials are aware of and

wary of the ‘peaceful revolution’ schemes that the US is

known to plot to subvert socialist/communist led regimes.

While some in the U.S. may claim that no such programs

exists, it should be clearly understood that the world’s

dictatorships and socialist/communist governments

(benevolent or otherwise) wholly believe that such programs

are very real. Because of this, many have put in place

measures to counter any such efforts. When Russia recently

tossed out (October, 2012) the U.S. Agency For Economic

Development for involving itself in its internal government

affairs, Vietnam’s leaders went through a convulsive fit of

apoplexy, turning over every rock they could find looking

for hidden American programs that might do them ill.

When

U.S. Congress or political leaders running for office

tout the need for countries like China to stop manipulating

their currency, or improve their human rights record as a

condition for stronger bilateral relations, all it does is

drive countries like Vietnam underground. Politically

motivated public statements that chastise those countries we

need most to improve our own ties with are of no value, and

only make America look like a bully of its own making.

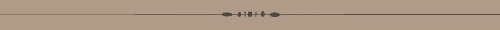

Looking at this from Vietnam’s perspective, what one sees is

this: closer ties with the U.S. may help Vietnam maintain

ownership and control over some of the Paracel and Spratly

Islands it lays claim to, wresting them from China’s grasp,

but on the other hand, these same closer ties may undermine

the CPV’s own legitimacy inside its own country. Which is

worse? Losing an island to China, or your whole country to

the United States?

When

U.S. Congress or political leaders running for office

tout the need for countries like China to stop manipulating

their currency, or improve their human rights record as a

condition for stronger bilateral relations, all it does is

drive countries like Vietnam underground. Politically

motivated public statements that chastise those countries we

need most to improve our own ties with are of no value, and

only make America look like a bully of its own making.

Looking at this from Vietnam’s perspective, what one sees is

this: closer ties with the U.S. may help Vietnam maintain

ownership and control over some of the Paracel and Spratly

Islands it lays claim to, wresting them from China’s grasp,

but on the other hand, these same closer ties may undermine

the CPV’s own legitimacy inside its own country. Which is

worse? Losing an island to China, or your whole country to

the United States?

In forming our new military policies as regards engaging

more closely with Vietnam, these factors must be kept in

mind. From the Vietnamese’s perspective they are asking Why is America

coming back here? For what purpose? More importantly, never

mind what we will gain, what will we lose if we engage with

the U.S. again?

Which

Big Brother Is Safer: China or the US?

For most Americans it seems a matter of fact that Vietnam

and China are close friends, reflecting a brotherly

relationship stemming from the sharing of a common border

for thousands of years; whereas the relationship between

Vietnam and United States is one based on suspicion and

caution born of past differences. That is not the case. From

Vietnam’s perspective, both China and the U.S. are two peas

in the same pod.

For

Vietnam, the U.S. is a dangerous country to liaise with,

notwithstanding the fact that it is located 8,500 miles away.

The same is true

for China though, except that since it is on Vietnam’s doorstep

this may make it even more dangerous for Vietnam to liaise

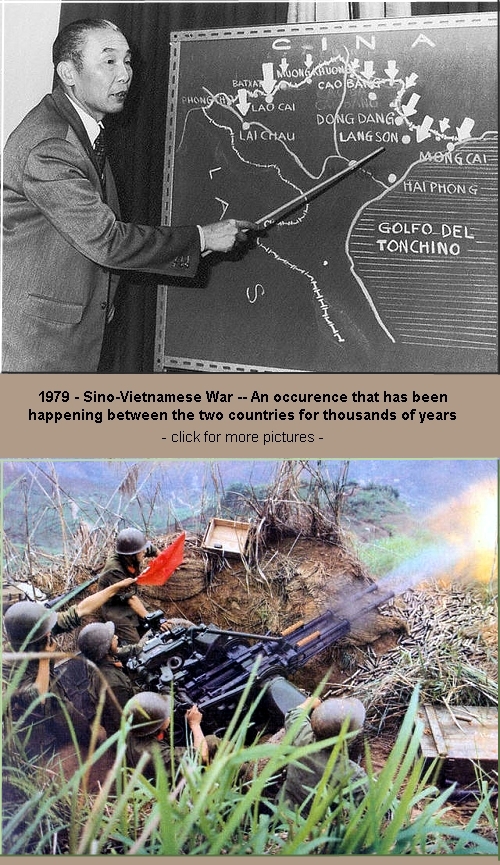

with than the U.S. In fact, many

Vietnamese feel that of the two China is much more

dangerous, having tried to subjugate Vietnam and make it a

vassal state ever since the Chinese general Zhao Tuo first

defeated the Vietnamese Emperor An Dương Vương in

207 BC. Since that date, Vietnamese leaders have been

fighting off repeated attempts by the Chinese to dominate

Vietnam. If truth be told, this long enduring enmity is what kept

Vietnam ‘in the closet’ for so many years after the

U.S.–Vietnam War was over.

For

Vietnam, the U.S. is a dangerous country to liaise with,

notwithstanding the fact that it is located 8,500 miles away.

The same is true

for China though, except that since it is on Vietnam’s doorstep

this may make it even more dangerous for Vietnam to liaise

with than the U.S. In fact, many

Vietnamese feel that of the two China is much more

dangerous, having tried to subjugate Vietnam and make it a

vassal state ever since the Chinese general Zhao Tuo first

defeated the Vietnamese Emperor An Dương Vương in

207 BC. Since that date, Vietnamese leaders have been

fighting off repeated attempts by the Chinese to dominate

Vietnam. If truth be told, this long enduring enmity is what kept

Vietnam ‘in the closet’ for so many years after the

U.S.–Vietnam War was over.

It wasn’t until Vietnam normalized relations with China in

the 1990s that Vietnam was able to break out of its

international diplomatic isolation and begin to work on

improving its own ties with the Association of Southeast

Asian Nations (ASEAN). Once relations with ASEAN

were returned to order, then Vietnam was able to put its

relations with the U.S. on a normal footing, from whence it

was then able to enjoy customary relations with all of the

remaining world powers. Lest this point of China dominating

Vietnam’s position on the world stage be missed, the reader

should recognize that for the first time since the socialist

republic came into being in 1945 Vietnam now enjoys global

acceptance, a event that could not happen without it

patching its relations with China and

kòu tóu -ing to China in the process.

What we can learn from this is that Vietnam learned a cruel

lesson when it took on China. Today still, bitter memories

of the 1980s and China’s efforts to subjugate and isolate

Vietnam from the world remain, with the result that the

Vietnamese do not want to repeat this experience. Therefore,

unless some other country (the U.S.?) is able to throw a

coat of protection over Vietnam’s shoulders… something that

insulates it completely from China’s pique, Vietnam is going

to go far out of its ways to maintain a peaceful and stable

relationship with China. The question is, does this intent

to maintain stable relations with China make the process one

of Vietnam’s top foreign policy priorities, or is the

priority to find someone with a big, enshrouding, warm and

safe coat in which to hide?

Part of the answer lies in whether Vietnam wants to continue

to pursue socialist economic management principles or not.

If so, then clearly the priority will trend towards China.

If not, then there is a big opening for the U.S. in

rebuilding both economic and military relations with

Vietnam. Economic, because that goes to the heart of what

Vietnam is seeking… a stable, growing economy that brings

independence from China to the country and a better quality

of life for its people… and military, because without the

U.S.’s military support Vietnam would soon find itself on

the losing end of the stick with China again.

It can be said then that ideological affinity between these

two purported socialist countries is either a major driving

force that keeps them together, or it is not. Considering

that with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern

Europe the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the VCP are the

only two major communist parties in the world still in

power, one would think that they look to each other as soul

mates, working to provide mutual backing and encouragement

to each other.

This author would say that this is not so. In fact, while

they do hold periodic conferences to discuss ideological

theories that have come under threat because of the

basically capitalist infrastructure they are both putting in

place, and exchange experiences on issues such as party

cohesion and warding off ‘peaceful evolution,’ they both

know that their real need is to build closer ties with

countries like the U.S., so that they can learn from our own

failures as regards the free enterprise economic system and

what makes it tick. If we in the military focus on this,

then we will quickly see that what Vietnam covets are not

closer ties to China, per se, but closer ties to

the U.S.; and as we said above, in order to do that they are

going to need much closer ties to the U.S. military… as only

the U.S. military can protect Vietnam from China’s anger

when she recognizes that she has been replaced by the U.S.

as Vietnam’s number one son.

Imagine

that: America’s Army, this time in north Vietnam, fighting

alongside the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) (Vietnamese:

Quân Đội Nhân Dân Việt Nam) to stop an invasion from

China? I’ll bet you didn’t think you would see that in your

lifetime?

Imagine

that: America’s Army, this time in north Vietnam, fighting

alongside the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) (Vietnamese:

Quân Đội Nhân Dân Việt Nam) to stop an invasion from

China? I’ll bet you didn’t think you would see that in your

lifetime?

Critics might say this will never happen. Economic

interdependence between the two countries is growing, and

China is Vietnam’s biggest trading partner. Bilateral trade

turnover reached US$27 billion and accounted for 17% of

Vietnam’s total trade in 2010.

Yes, this is all true. But so is it true that while China is

beginning to become a consuming society that buys from the

rest of the world, the U.S. is already one, and has been the

world’s largest consuming society since the late 1890s. So

again, if you are Vietnam and need to develop a higher

degree of integration between your economy and that of

another, which would you pick: the one on your border trying

to take the islands you claim title to, and subjugate you in

the process, or the one 8,500

miles away that will a) help you protect your islands, b)

provide you with capital to build your economic

infrastructure, c) buy the goods that new economic

infrastructure manufactures, and d) protect you from that

bully to your north?

Add to this China’s unprecedented military buildup, its new

face showing signs of expansionism, continuing territorial

disputes between the two countries, and its past 3,000 year

aggressive history with respect to Vietnam, and it is easy

to see that Vietnam today sees this far more powerful China

as a most serious threat. It may be true that Vietnam cannot

today afford a more hostile relationship with China, but

then again it also cannot afford to sit back and do nothing,

possibly sacrificing its national sovereignty and

territorial integrity in the process. What Vietnam must do,

and everyone knows it, is reach out to a foreign partner,

building relations with it that will help it deter Chinese

aggression, and hopefully help build the Vietnamese economy

in the process.

Who better to do that with than the United States? More

accurately, what other country on earth would even consider

going to Vietnam’s rescue, possibly putting itself in the

line of Beijing’s fire in the process?

Only America.

Where Do We Stand Today?

For those unfamiliar with the current state of relations

between the U.S. and Vietnam, an effort to make it stronger is already

underway. After the normalization of relations between our

two countries in 1995, bilateral dealings advanced rapidly,

to such a point that today there are talks on both sides

about establishing a strategic partnership between the U.S.

and Vietnam. Economic ties, in particular, have deepened to

the extent that they provide a solid footing for even more

bilateral cooperation. Yet these economic ties could be

better. What is needed, as an example, is for the Vietnam

Vets that are now mature and running successful companies in

America to expand their operations into Vietnam. If they

did what they would find are welcoming hands and open arms,

from a people more curious about who these Americans are

that used to fight them, than anything else. Vietnam needs

American businesses to invest in it, and American business

needs to do so, if only to stem China’s rise and threats to

the U.S. on other fronts.

From

2001 to 2011 two-way trade between the U.S. and Vietnam

increased more than 12 times to US$21.8 billion, nearly

matching that of trade between Vietnam and China. More

important, the US is currently Vietnam’s biggest export

market, displacing China and accounting for nearly 1/5 of

Vietnam’s annual exports by value. In 2010 the U.S. became

Vietnam’s seventh largest foreign investor in the country.

From

2001 to 2011 two-way trade between the U.S. and Vietnam

increased more than 12 times to US$21.8 billion, nearly

matching that of trade between Vietnam and China. More

important, the US is currently Vietnam’s biggest export

market, displacing China and accounting for nearly 1/5 of

Vietnam’s annual exports by value. In 2010 the U.S. became

Vietnam’s seventh largest foreign investor in the country.

What does all of this tell us? One thing it says is that the

VCP is clearly willing to promote further ties with the

U.S., not only for economic value but for strategic reasons

too. Considering that this is undoubtedly in our own

economic and strategic interest, one thing we should guard

against is letting the public discussions about Vietnam’s

human right conditions grow out of control and undermine this

process.

Yes, America needs to champion human rights, but not to the

point that our talk of it undermines our ability to do

something about actually improving human rights, such as by

actually getting American’s into a country, working with its

people on a daily basis, and transferring our values to the

locals through deeds, as opposed to political talk and

tongue wagging on Capitol Hill. At the moment those in

Vietnam who fear the hegemony of U.S. imperialism are

watching closely for a ‘peaceful evolution’ scheme to be

launched against the VCP. And the avenue they think this

scheme will come down is labeled “human rights.”

In this regard, making the further

development of bilateral relations between our two countries

conditional on improvements in Vietnam’s human rights

record, as some U.S. politicians are calling for, would be a

grave mistake. All it would do is push Vietnam back into

China’s arms, where neither a net gain to America’s economic

or strategic values (as re. Vietnam) would take place, nor a

gain for those suffering from human rights abuse in Vietnam.

The answer is not to ratchet up the rhetoric about what’s

wrong with Vietnam, but to engage with it and quietly go

about demonstrating America’s values from within the

country.[1]

With a softly, softly approach to Vietnam’s human rights

issues the U.S. can expect to see greater flexibility as

regards Vietnam agreeing to be brought on board as a member

of the Co-security Sphere discussed in our earlier articles.

This most especially as the role the contested islands play

in Vietnam’s economy is significant. In 2010 the revenue

generated by Vietnam’s national oil and gas corporation (PetroVietnam)

accounted for 24% of the country’s GDP. Underlining the

importance of this, most of PetroVietnam’s revenue was

generated from operations in the South China Sea, in the

very area China is contesting.

With a softly, softly approach to Vietnam’s human rights

issues the U.S. can expect to see greater flexibility as

regards Vietnam agreeing to be brought on board as a member

of the Co-security Sphere discussed in our earlier articles.

This most especially as the role the contested islands play

in Vietnam’s economy is significant. In 2010 the revenue

generated by Vietnam’s national oil and gas corporation (PetroVietnam)

accounted for 24% of the country’s GDP. Underlining the

importance of this, most of PetroVietnam’s revenue was

generated from operations in the South China Sea, in the

very area China is contesting.

However, the benefits to be had from Vietnam’s territorial

waters extend far beyond oil and gas. Fishery industries,

tourism, maritime transportation, port services, and others

all factor into the matter. The VCP projects that by 2020

the marine economy could account for 53%–55% of GDP and

55%–60% of all exports. Thus, with oil and gas being tied to

ownership of this region of the Pacific, maritime

industries, and national security, Vietnam is sure to see

offers from America of help as a welcomed approach.

The fact is, China has long obstructed Vietnam’s economic

activities in the South China Sea. In addition to seizing

hundreds of Vietnamese fishing boats every year, China has

aggressively pressured Western oil and gas companies to

cancel their ventures in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone

(EEZ). In a now legendary event in May 2011, a Chinese

marine surveillance ship harassed and then deliberately cut

the cables of a PetroVietnam survey vessel deep within what

should be considered Vietnam’s EEZ. The incident sparked a

wave of international criticism over China’s increasing

brazenness in the South China Sea, in favor of Vietnam.

With these things happening, there has never been a better

time for the U.S. military to extend its hand to the

Vietnamese military, to build a solid, mutually respectful,

and mutually beneficial relationship.

What Can America’s Army

Contribute To Vietnam’s?

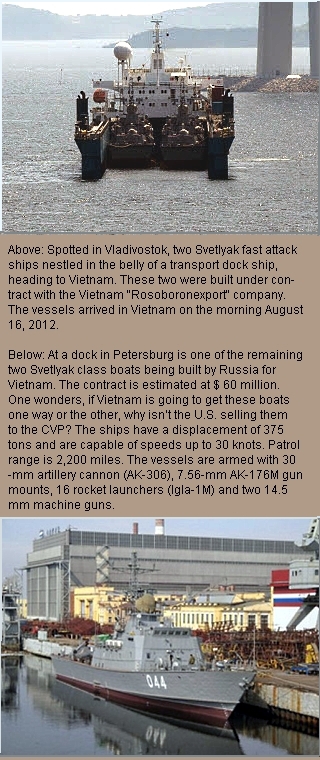

There is a massive gap in military strength between that of

Vietnam and China. Even so, Vietnam is uncompromisingly

working to develop capabilities to deter Chinese aggression.

First, it’s been speeding up its Navy’s military

modernization, doing so by upgrading naval capabilities by

acquiring modern Svetlyak class fast attack craft and

Gephard class frigates. It is also awaiting 6 Kilo class

submarines that will start being delivered in 2014, as well

as a series of Bastion land-based anti-ship cruise missiles,

all with extended range artillery munitions.

There is a massive gap in military strength between that of

Vietnam and China. Even so, Vietnam is uncompromisingly

working to develop capabilities to deter Chinese aggression.

First, it’s been speeding up its Navy’s military

modernization, doing so by upgrading naval capabilities by

acquiring modern Svetlyak class fast attack craft and

Gephard class frigates. It is also awaiting 6 Kilo class

submarines that will start being delivered in 2014, as well

as a series of Bastion land-based anti-ship cruise missiles,

all with extended range artillery munitions.

Recognizing that these are short term measures, Vietnam is

developing its own defense industry via both co-production

agreements with other countries, as well as by underwriting

technology transfers. On this latter point, Vietnam said it

is building Sigma class corvettes with help from the

Netherlands, as well as a series of patrol boats modeled on

the Svetlyak offshore patrol vessel.

Even considering these steps, Vietnam’s naval investment is

no match for that of China, and so it must find a larger

naval power to partner with. Enter the U.S. Navy. Behind all

of the rhetoric what one will see is that, although Vietnamese leaders are saying

that Vietnam will be self-reliant and never seek to enlist

foreign assistance in solving disputes with other countries,

it is actually making concrete efforts to reach out to

foreign powers as a counterweight to its substantial

defenselessness against China.

If this is the case with regard to its navy, then what of

its army? Surely, in any military confrontation between

Vietnam and China at sea, the Chinese are going to

supplement their naval actions with cross border attacks

too. Can Vietnam’s army stand up to China’s? One thinks not.

And

therein an opportunity for the U.S. Army to begin to develop

strategic relations with the Vietnamese military, just as

the U.S. Navy has done with Vietnam’s own Navy.

What can a relationship with the U.S. Army bring to Vietnam?

Part of the answer is that if Vietnam is to have a

relationship with the U.S. government then it needs to have

relationships with all of the elements that make up

our government, from the State Department to our Army and

Navy. It’s not a matter of the U.S. Army wanting a

relationship with Vietnam, it’s a matter of the Army having

to have one, in order to support the strategic goals America

has in this region of the world. Such goals should include

contributing to regional peace, security and prosperity, as

well as the further economic transformation and

international integration of Vietnam into the international

community, most especially the countries of the Asia–Pacific

region. In that regard, closer relations between the U.S.

Army and the Vietnam People’s Army will:

• Lay the groundwork for regional peace and security by

causing the VPA to engage in constructive participation in

the international and regional institutions (such as the

previously mentioned Co-security Sphere group) that promote

peacekeeping operations, both within and external to UN

frameworks.

• Help assure that the world and China in particular see

Vietnam not as a potential challenger to regional order and

stability, but as an independent, open and strong country

working to promote peace. For the other countries of

Southeast Asia a strong Vietnam is much preferred to one

that is weak, inward looking, and China dependent.

• Finally, the economic growth and international integration

of Vietnam will contribute to regional prosperity and

therein encourage the transformation of Vietnam into a more

open and democratic society, thus helping to change its

human rights stance over the long run. As all would agree,

international socialization causes countries to adopt

universal values, norms and standards, thus moving the

countries involved towards greater respect for the rights of

their own citizens.

US-Vietnam Defense Relations, The Road Forward

What is needed in all of this are a set of practical steps

designed to establish and carry out a program focused on

increased bilateral defense cooperation. Already some work

along this line is underway, but more must be done. One can

see both the good work that has been done to date by

looking, as an example, at Secretary of Defense Panetta’s

recent trip to Cam Ranh Bay. One can also see from this the

work that still needs to be done.

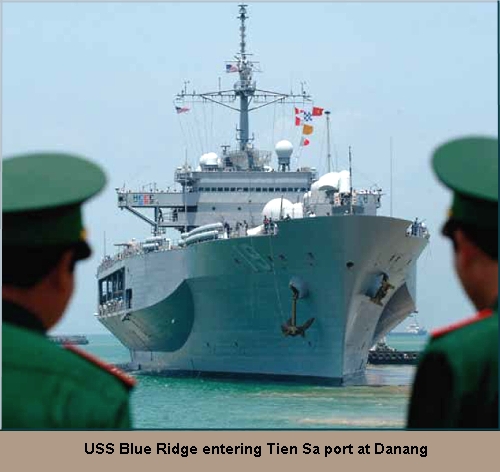

While

Panetta was there on board the USNS Richard Byrd, he wasn’t

there on a U.S. warship. At this stage the Vietnamese will

not allow U.S. warships to dock in Cam Ranh, only cargo

ships like the Byrd; ships operated by the Navy’s Military

Sealift Command, ones primarily manned by civilian crews. On

the other hand, U.S. Navy warships are allowed to dock in

Vietnam in the context of normal and routine naval

diplomacy, if they dock at Da Nang. The point being, while

inroads are being made, there is still a long way to go

before military-military relations are fully normalized.

While

Panetta was there on board the USNS Richard Byrd, he wasn’t

there on a U.S. warship. At this stage the Vietnamese will

not allow U.S. warships to dock in Cam Ranh, only cargo

ships like the Byrd; ships operated by the Navy’s Military

Sealift Command, ones primarily manned by civilian crews. On

the other hand, U.S. Navy warships are allowed to dock in

Vietnam in the context of normal and routine naval

diplomacy, if they dock at Da Nang. The point being, while

inroads are being made, there is still a long way to go

before military-military relations are fully normalized.

It’s not that the Vietnamese don’t want U.S. warships in Cam

Ranh, it’s that they are holding out this tidbit as a cherry

to be exchanged when we lift restrictions on the sale of

better arms to the Vietnamese military. What we should do is

complete this bargaining effort on their part: give them a

roadmap leading to better arms, including in it a schedule

for the release of the arms involved in a manner that

balances delivery of the arms with closer relations between

the branches of our military that govern use of the arms

involved. Thus, on the Navy’s side, bargain improvement in

naval arms for closer cooperation between the commanders of

our two navies, including joint training exercises in the

process. And the same for the Army; provide them with better

combat arms in return for joint training exercises that see

Vietnam’s army training at U.S. bases in America, in return

for our doing the same at bases within Vietnam.

What is needed is an across the board ambitious program of

cooperation between our two militaries, one that focuses

from our side on forging a closer defense partnership by

drawing the Vietnamese military into the Co-security Sphere

group.

Clearly, this will require flexibility and patience on our

part, along with a set of very capable senior Officers who

have the authority to move such a program forward. To be

managed by both U.S. Navy and Army Officers, these on the

ground military policy implementation specialists should be

fully familiar with not just the U.S. military's strategic

imperatives with regard to Vietnam, but also how our and

Vietnam's State Department works. They should have prior

experience in both foreign relations and nation building,

and be able to not just think outside of the box but work

outside of it too. The reason for this is that the

Vietnamese, while fearful of China, are relatively

comfortable with the existing level of activity in defense

relations between us. To overcome this reticence on their

part to expand relations we are going to need military

leaders that can show them that if such a closening of ties

takes place it will support and be congruent with Vietnam’s

own national interests. Basically we must show them that we

can do more than just help support their already stated

commitment to regional engagement as per the rules laid out

by ASEAN, improving on them by giving Vietnam more control

and influence over the entire process.

Some might say that these intentions are all well and good,

but what makes us think that Vietnam will work with our Army

as closely as we wish? Surprisingly, the answer is that they

already have. That is, the VPA has already demonstrated a

remarkable capacity to work closely with the U.S. Army when

they joined in solid fellowship with us in the late 1980s

and 1990s in conducting a series of successful joint field

activities to account for U.S. POWs and MIAs from the

Vietnam War. During these efforts both sides worked very

much in faithful consideration of each other’s needs to

increase the effectiveness of the planning and execution of

these joint efforts. The result was a decade of lessons

learned, on how to coordinate, communicate, enhance safety,

manage transportation, and otherwise support each other on

the basis of a host-nation, guest-nation relationship. All

one needs to do then is extend this early coming together to

today, to encompass a joint effort to stymie China’s

expansionist tendencies.

From a strategic imperative standpoint this means that the

U.S. Army should expand its effort to assure that each party

has a chance to educate and train the other on how it sees

and prefers to create a series of jointly tailored and

undertaken military programs that address (1) logistics,

services, transportation, and facilities support as may be

needed in countering China’s aggression; (2) means to

provide humanitarian response efforts to either civil unrest

or natural disaster incidents; (3) means to participate in

joint peacekeeping efforts; and (4) in the end, ways to work

together where each shares a responsibility in a pooled

mission that might be defined as an as yet unknown but

combined military operation.

Once this has been done, then the two militaries need to

operationalize the programs they jointly defined by

instituting bilateral communication, coordination, and

command exercises. This they must do by developing

operational contact that permits both sides to observe the

effects of command and control on the other, preferably by

allowing the Vietnamese to train at U.S. continental bases

and facilities, and the U.S. to train at VPA bases within

Vietnam.

To be fair, some of this has already been done, as in the

case of the late 1990s programs that saw U.S.–Vietnamese

defense relationships trying to move forward based on a

series of three activities: multilateral conferences and

seminars hosted by the U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM);

senior-level military visits; and practical bilateral

cooperation in areas such as search and rescue (SAR),

military medicine, environmental security, and de-mining.

Yet while a good start, we say again that the effort

undertaken falls short of what is needed. Further,

relationship building between our two militaries has not

progressed fast enough, and more attention must be given to

this matter. And while we do agree that there are many and

varied reasons for the failure to move the relationship any

further along, such as the U.S. congress getting involved by

requiring that every Vietnamese officer offered

cross-relations training in peacekeeping activities be

certified as not having been involved in previous human

rights violations, the fact still remains: today we face a

historic and once in a century opportunity to leverage

China’s aggression over the disputed islands to our benefit

with Vietnam. Politicians need to stand aside and let the

State Department and DoD do its work, building a new, long

term relationship with Vietnam… one that includes our two

militaries working together as closely as we do with

Australia or Japan, if not closer. There is no reason why

this past enemy should not become a future close friend.

The bottom line: good progress has been

made, but much more needs to be done. For example, in

mid-2011 Vietnam enrolled the first VPA officer in our

National War College. Senior Colonel Hà Thành Chung,

a department head in the Vietnamese Military Science

Academy, joined the class of 2011–2012 for a year of study

as an International Fellow. Similarly, on September 20,

2011, the U.S.’ Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for

South and Southeast Asia and Vietnam’s Deputy Defense

Minister signed an MOU aimed at “advancing bilateral defense

cooperation.” The document identified five areas that both

sides will work to expand cooperation on: (1) maritime

security, (2) search and rescue, (3) United Nations

Peacekeeping Operations (UNPKO), (4) humanitarian and

disaster relief (HADR), and (5) collaboration between

defense universities and research institutes.[2]

To do this though the U.S. will need to see and understand

that the Vietnamese do not presently view deeper military

relations with the U.S. as a zero-sum game relating to

China. They feel that engaging more with the U.S. should not

necessarily necessitate engaging less with China. From this

one can see that Vietnam is comfortable with a foreign

policy that offers many options in the face of Chinese

assertiveness, and will likely continue to prefer such until it is

burned in a hot, at-sea exchange of fire with China—one that

eventually ebbs not because of China’s ability to control

its trigger finger, but because of the presence of U.S.

warships over the horizon. At that time the Vietnamese will

recognize the critical importance of an effective, friendly

relationship with the U.S., one deeper than that which

exists at this time.

Until that day comes, the U.S. military should continue to

push for these tactical objectives:

• Develop ways to assure better communication at all levels of both

militaries. In this regard the U.S. should push for increased training at

continental U.S. bases of VPA staff in planning,

communication and coordination in inter-military roles that

relate to missions involving civil and natural disasters, to

be followed with joint military missions relating to

peacekeeping and territorial protection.

• Expand the above programs to include additional training

in 1) logistics, services, transportation, and facilities

support; 2) evacuation and sheltering of displaced

populations during civil and natural disasters; 3) the roles

and missions of peacekeeping forces; and 4) roles, missions,

and responsibilities of the military in international

combined military efforts.

• As a first step towards causing Vietnam to join as a

member of the Co-security Sphere group, the U.S. should urge

Vietnam to become a joint member of a regional

search-and-rescue group. This will help migrate the

relationship from simple information sharing to involvement

in actual command exercises.

• Training should be supplemented with inclusion in joint

exercises with Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the

Philippines, where command and operations, strategic

communications, coordination and support can be demonstrated

to the VPA, even though they may have no formal

military-to-military relations with these other countries in these

specific

areas. This will show the willingness of all of the

countries of South and Southeast Asia to bring Vietnam into

their realm of cooperation with the U.S.

• Reluctant or not, continue to place pressure on Vietnam to

participate in or at a minimum monitor force exercises on

the ground, offering them both learning objectives and

training modules that they can inernalize at their leisure.

• Being that in 2005 Vietnam signed an agreement with the

U.S. to participate in the International Military Education

and Training (IMET) program (for non-lethal areas), the U.S.

should carefully press the Vietnamese to expand the course

structure from military medicine, science and technology to

include a few modest military training team (MTT) subjects

such as might be useful in a joint exercise in territorial

protection... exercises such as those that might be needed

to keep China from gobbling up one of Vietnam's islands.

• And as Vietnam makes progress in these areas, the U.S.

should reduce barriers that exist to Vietnam participating

in lethal arms purchases from the U.S., allowing it to

participate as others do in the U.S.’ foreign military sales

(FMS) program in ways that ultimately enhance the

U.S.–Vietnam strategic relationship.

In our view, if the goal is to build strong and lasting

relationships with the middle power countries of Asia,

relationships that can help the U.S. counter China’s

increasing military aggression, then with respect to Vietnam

these are the types of initiatives that the U.S. Department

of Defense should pursue. They will contribute to a better,

closer, more sound, and longer lasting series of bilateral

military engagements, engagements of a type that will build

trust between the U.S. and Vietnamese military.

- - - -

Next month: Strategic Military Imperatives – Our

Conclusions Regarding Strategic Imperatives for Asia.

Footnotes

[1] The US has already taken a number of actions, not all

of which are conducive to improved relations with Vietnam. One involves an

annual review of the human rights situation in Vietnam, and includes calls

for interventions with Vietnamese authorities to get a number of political

dissidents released from detention. Additionally, a bill that seeks to link

US aid with Vietnam’s human rights record has been passed by the House of

Representative several times, but has never made it through the Senate.

Hopefully, cooler heads will prevail and recognize that these forms of

“engagement” have failed to work in the past, and considering how critical

it is that the U.S. find a way to thwart China’s expansionist tendencies, it

may just be that human rights needs in Vietnam should not be prioritized

above the U.S. gaining a) more thorough access to the country, and b)

establishing for the U.S. strategic abilities to counter China from within

Vietnam’s borders.

- To return to your place in

the text click here:

[2] Merle Pribbenow and Lewis M. Stern, “Notes on Senior

Colonel Hà Thành Chung,” prepared for the National Defense University, March

24, 2011.

- To return to your place in

the text click here:

Additional Sources

Carlyle A Thayer and Ramses Amer, Vietnamese foreign policy in transition,

St Martin’s Press, New York, 1999.

X Linh and T Chung, ‘Mỹ Muốn Việt Nam Cải Cách Doanh Nghiệp Nhà Nước’ [US calls

for reform of Vietnam’s state-owned enterprises], Vietnamnet, 24 February

2012.

Nicholas Khoo, Collateral damage: Sino-Soviet rivalry and the termination of

the Sino-Vietnamese alliance, Columbia University Press, New York, 2011.

Vietnam News Agency, ‘Mỹ Muốn Nâng Tầm Quan Hệ Đối Tác Chiến Lược Với Việt Nam’ [US wishes to promote strategic

partnership with Vietnam], Vietnamplus,11 November 2011.

Le Hong Hiep, ‘Vietnam eyes middle powers’, The

Diplomat, 5 March 2012.

Various additional writings of Mr. Le Hong Hiep: Mr.

Le Hong Hiep is a lecturer in the Faculty of International Relations,

Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, and a PhD candidate in

Politics at the University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force

Academy, Canberra. Before joining the VNU, Mr. Le worked for the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs of Vietnam from 2004 to 2006. His articles and analyses have

been published in The Diplomat, East Asia Forum, BBC and Vietnamnet.

"Vietnam’s strategic trajectory: From internal

development to external engagement;" Strategic Insights, Australia Strategic

Policy Institute.

Credit for many of the bullet point viewpoints

expressed herein belong with Colonel (R) William H. Jordan. Col. Jordan

served as a Northeast Asia Foreign Area Officer from 1979 to 1997. He was

the Principal Advisor to the Secretary of Defense on POW/MIA Affairs from

1990 to 1993, and subsequently commanded the U.S. Army Central

Identification Laboratory in Hawaii.

Additional credit for concepts expressed here is due

Mr. Walter Lohman, Director of the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage

Foundation.

Lewis M. Stern, “National Defense University:

Building Strategic Relations with Vietnam,” Joint Forces Quarterly, April

2012.

Have a comment on this article? Send it to us. If you

are a member of the Association we will gladly publish it. If you are not,

well, it only costs $30.00 a year to become a member and have your views

heard... and because we are a fully compliant non-profit organization your

payment is tax deductable. If you would rather not become a member a $30.00

donation to our

Scholarship Fund will accomplish the same, and we

will gladly publish your views on this article.