Why

was this so difficult to do in WWII? In great measure it was because back

then most means of military communication in use was based on advances made

in the civilian sector, and many times while these advances proved excellent

they didn’t prove up to the challenges of war. In particular, communication

as it existed at the beginning of WWII fell into two categories: minor

advances in technology and creative advances in the form

of communication available.

Why

was this so difficult to do in WWII? In great measure it was because back

then most means of military communication in use was based on advances made

in the civilian sector, and many times while these advances proved excellent

they didn’t prove up to the challenges of war. In particular, communication

as it existed at the beginning of WWII fell into two categories: minor

advances in technology and creative advances in the form

of communication available.

In terms of the forms of communication

available at the beginning of World War II the military equivalents then

were little different than the nonmilitary varieties used at that time. For

example, the command teletypes used between various Army field headquarters

in Europe were essentially the same as those one would have found on Wall

Street or the Mercantile Exchange in Chicago, to transmit news or stock

exchange ticker data. Even the exciting new “invention” of the

motor-cycle messenger that the Army Signal Corps so effectively

deployed throughout North Africa was little more than the motorized

equivalent of the old hand-carrying Western Union bicycle boy that plied the

streets of New York City. While their use was distinctive, and their

importance beyond question, they were nevertheless nothing more than

motorized forms of civilian mail carriers. And so it was with every other

form of communication then available, from radio broadcasting to control

towers, telephones to teletypes, and even railway semaphores… it was all

little different from that available in

the

civilian world.

the

civilian world.

Which is why the Signal Corps was needed. At the

beginning of WWII the Signal Corps was called on to bring a little

organization to the concept of military communication by finding a way to

not just repurpose what was available in the civilian world but also advance

its development to suit the needs of the armed forces, while at the same

time extending the known capabilities of communication far beyond that

available to include forms and functions unheard of and un-thought of by

either the civilian world or the enemy.

What resulted was an effort to develop better forms of

communication along three main axis: general sensory signaling (typically

signaling that was nonelectrical in nature), electrical signaling (typically

as found and used over wires), and electrical signaling without the use of

wires.

As an aside, the reader should recognize that the

effort the Signal Corps undertook at the beginning of WWII to develop more

effective means of communication in these three areas was a parallel effort.

That is, development in these areas did not take place in a line of

succession but simultaneously across all fronts. The result of this parallel

effort in turn caused the structure of the Signal Corps to need to be

changed… from what it was prior to WWII into what it became during the war,

and in many, many instances even up until today. That is, the operational

form that is seen in the Signal Corps today got its start early in WWII,

with modernization and improvements being made along the way, in response to

the need to develop world class forms of combat communication across the

three areas listed above.

Looking

at each of these in turn, we will classify them as Sensory Signaling (most

usually of a visual or audible type), Wire Based Electrical Signaling, and

Non-wire Based Electrical Signaling.

Looking

at each of these in turn, we will classify them as Sensory Signaling (most

usually of a visual or audible type), Wire Based Electrical Signaling, and

Non-wire Based Electrical Signaling.

Sensory Signaling

Everyone knows by now that back in the Civil War Brevet

Brigadier General Albert J. Myer codified an effective means of semaphore

signaling, called within the Army at the time and even today wigwag

signaling. What few of us today will recall however is that this form of

signaling was still in solid use at the beginning of WWII, even while Samuel

F. B. Morse's telegraph approach to messaging was slowly making its way

throughout the military. The reason wigwag signaling existed simultaneously

with telegraphy was that they both served a purpose, and while in many

instances telegraphy could easily replace wigwag, in others wigwag provided

the only effective means of getting the message through… such as in the case

of two ships at sea in need of passing encrypted, silent messages between

themselves. Even so, as newer forms of tactical combat took the field during

WWII Myer’s systematic wigwag flag based signaling quickly reached its

limits. Morse's approach on the other hand seemed to show no boundaries to

its capabilities, especially if it was coupled with non-electrical

signaling.

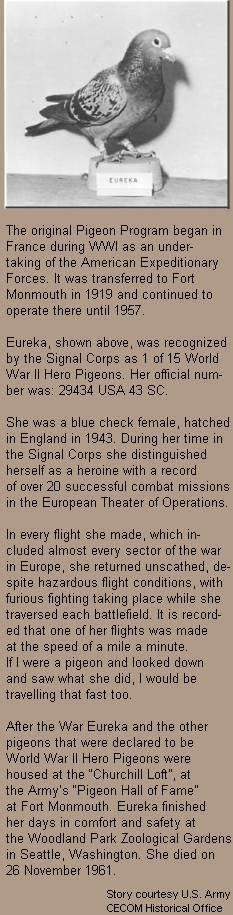

In

the interim though—that is, the interim in time that it would take between

the state of communication at the beginning of WWII and where it needed to

get to if the war was to be won—the Signal Corps had to make do with what it

had. The result was that a whole series of elemental forms of signaling were

used to fill the void between wigwag flags and telegraphy. Among the forms

used to fill the needs of sensory signaling were not just the wigwags and

semaphores, but also pyrotechnics, airplanes reading pieces of colored cloth

spread on the ground (as was done in WWI), and most importantly the old

standby pigeon.

In

the interim though—that is, the interim in time that it would take between

the state of communication at the beginning of WWII and where it needed to

get to if the war was to be won—the Signal Corps had to make do with what it

had. The result was that a whole series of elemental forms of signaling were

used to fill the void between wigwag flags and telegraphy. Among the forms

used to fill the needs of sensory signaling were not just the wigwags and

semaphores, but also pyrotechnics, airplanes reading pieces of colored cloth

spread on the ground (as was done in WWI), and most importantly the old

standby pigeon.

In the early days of WWII pigeons were still a primary

means of signaling and not surprisingly so were sirens and whistles. The

problem with all of this though was that because these were sensory forms of

signaling they all held one or more inherent limitation. So while they had

value as a means of controlling railroad traffic (flags and beacons),

sorting out supplies on a beachhead (wigwag), or passing messages between

ships (blinking lights), they were not invisible to the enemy, were easy to

misread, were of limited capacity, and were often useless during foul

weather. While primitive, they had value, yet no modern war was ever going

to be won with the limitations these forms of communication held. What was

needed instead was fast, reliable, messaging that guaranteed the fewest

mistakes possible. Or put another way, these simple forms of sensory

signaling lacked capacity, speed, and precision. Electrification and the

application of emerging technologies offered a solution to this problem.

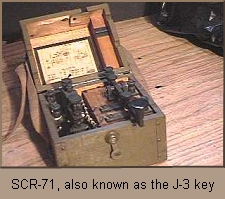

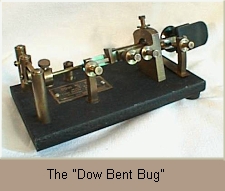

Wire Based Electrical Signaling

Considering that telegraphy had already been developed

and deployed in the civilian world by the time of WWII it was only natural

to paint it olive drab and drag it onto the field of combat, along with all

of its cousins, in every form available. Thus Signal Corps troops marched

into the field alongside combat troops, deploying wire based electrical

signaling paraphernalia along the way. Overnight the U.S. military began to

see cables being strung, telegraphs being pounded, telephones being cranked,

and hear teletypes clattering away. So pervasive was this effort that

throughout World War II these forms became the predominant and principal

form of communication the Signal Corps depended on. And while for the most

part they held the field even these did not fill the void or serve the

needs that combat commanders cried for. As a result non-wire based

electrical signaling began to take its rightful place on the battlefield,

and ever since the world of communication—both military and civilian—has

never looked back.

Non-wire Based Electrical Signaling

With rapidity wireless devices

began to leap from theoretical concepts bandied about the halls at Ft.

Monmouth, through design and testing and onto the manufacturing production

lines of companies across America. With the Signal Corps driving

development the time taken to go from concept-to-reality shrunk from the

slow leisurely pace it held before the war to, in many cases, only a few

months. The fact is, the pace of technological development attained by the

Signal Corps from the beginning of WWII up through the last third of the war

was the first practical example of the existence of Moore’s Law, a concept

first explained by Gordon E. Moore (one of the founders of Intel) in 1965...

a time at which WWII was only a distant memory.[1]

Among the inventions that flowed from Signal Corps

supported efforts were the radio, radiotelegraph, radiotelephone,

radio-teletype, television, and RADAR. However, as opposed to how we see

many of them today, their value was not as a means of entertainment but in

their ability to achieve the hallowed goals of capacity, speed and precision

in communication during combat. For example, the accomplishments of radio

transmission in increasing the rate of teletype transmission from the

average Morse Code rate of 30 WPM to an electric teletypewriter rate of over

a hundred words a minute, transmitted reliably and without error, had a huge

impact on the effectiveness of military communication. Even the ability to

predict the impact of weather on combat operations improved because of

Signal Corps' sponsored communication development. In this regard, reporting

the weather locally by radiosonde became the standard. And who can forget

the enormous impact the “handie-talkie” (a term Winston Churchill used to

refer to the SCR-300, a device the rest of us call a walkie-talkie) had on

combat. Something we think of today as an antiquated form of radio

telephony, back when it was first introduced in war the walkie-talkie

brought startling changes to how tactics were carried out.[2]

The

astute reader may have noticed our listing of television above, and wondered

about its value during WWII, as obviously the form we see it in today had

not yet come into existence until after the war was over. During World War

II however it made its appearance in another form. Rather than finding a use

in homes so that housewives could see Arthur Godfrey (whose first appearance

on TV was in 1948, when his Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts began to be

simultaneously broadcast on radio and television), television found its

first use during WWII as a form of RADAR. One could even say that RADAR was

the crown jewel of communication development during the second world war.

With RADAR the military was able to guide aircraft at a distance, help them

return to base safely, land in inclement weather, and of course detect the

presence of enemy aircraft. It also allowed the military to map land masses

as well as the approach of land while at sea; map storms, guide searchlights

so that antiaircraft guns could hone in on targets, discover ships at sea

and submarines under the sea, guide antiaircraft artillery, and in a revised

form guide torpedoes. And it did all of this with unheard-of precision. On a

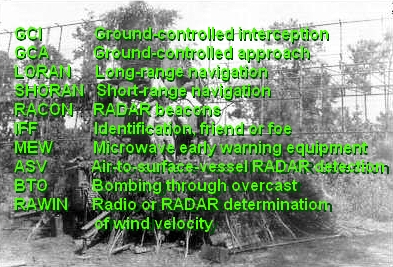

technical basis it allowed the development and use of tactics and techniques

that included GCI, GCA, LORAN, SHORAN, RACON, IFF, MEW, ASV, BTO, and RAWIN.

Clearly, back in World War II RADAR was the new black magic.

The

astute reader may have noticed our listing of television above, and wondered

about its value during WWII, as obviously the form we see it in today had

not yet come into existence until after the war was over. During World War

II however it made its appearance in another form. Rather than finding a use

in homes so that housewives could see Arthur Godfrey (whose first appearance

on TV was in 1948, when his Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts began to be

simultaneously broadcast on radio and television), television found its

first use during WWII as a form of RADAR. One could even say that RADAR was

the crown jewel of communication development during the second world war.

With RADAR the military was able to guide aircraft at a distance, help them

return to base safely, land in inclement weather, and of course detect the

presence of enemy aircraft. It also allowed the military to map land masses

as well as the approach of land while at sea; map storms, guide searchlights

so that antiaircraft guns could hone in on targets, discover ships at sea

and submarines under the sea, guide antiaircraft artillery, and in a revised

form guide torpedoes. And it did all of this with unheard-of precision. On a

technical basis it allowed the development and use of tactics and techniques

that included GCI, GCA, LORAN, SHORAN, RACON, IFF, MEW, ASV, BTO, and RAWIN.

Clearly, back in World War II RADAR was the new black magic.

While

many of these forms of “television” were in fact experimented with and

developed in the 1930s, they did not come to the fore as military hardware

and systems until WWII, when they were proven to be desperately needed.

Before WWII much of the experimentation on the technologies that led to

forms of TV communication was done (1917 - 1919) at Camp Vail, in

east-central New Jersey. In 1925 when the name of the camp/fort was changed

to Fort Monmouth, and cost cutting measures forced the Electrical and

Meteorological Laboratories and the Signal Corps Laboratory at the National

Bureau of Standards to be relocated to Ft. Monmouth, and subsequently

renamed the SCL, with a whopping 5 officers, 12 enlisted men, and 53

civilians, things really began to heat up. By the time 1934 rolled around

radio-based target detection was well along in development. With a magnetron

on loan from RCA research progressed to the point that RPF (radio position

finding) became a viable technology. Interestingly, this coincided with the

construction of Squire Hall (1935), a building all who have been stationed

at Ft. Monmouth know well.

While

many of these forms of “television” were in fact experimented with and

developed in the 1930s, they did not come to the fore as military hardware

and systems until WWII, when they were proven to be desperately needed.

Before WWII much of the experimentation on the technologies that led to

forms of TV communication was done (1917 - 1919) at Camp Vail, in

east-central New Jersey. In 1925 when the name of the camp/fort was changed

to Fort Monmouth, and cost cutting measures forced the Electrical and

Meteorological Laboratories and the Signal Corps Laboratory at the National

Bureau of Standards to be relocated to Ft. Monmouth, and subsequently

renamed the SCL, with a whopping 5 officers, 12 enlisted men, and 53

civilians, things really began to heat up. By the time 1934 rolled around

radio-based target detection was well along in development. With a magnetron

on loan from RCA research progressed to the point that RPF (radio position

finding) became a viable technology. Interestingly, this coincided with the

construction of Squire Hall (1935), a building all who have been stationed

at Ft. Monmouth know well.

As RPF moved through its development it advanced from

simple target awareness to microwave usage, Doppler shifted signaling,

bi-static transmission and antenna arrangements, beat detectors, azimuth and

elevation measurement development, use of dipoles on wooden frames as

antennas (see picture behind acronym list above), ring oscillators, antenna

lobe switching, and much, much more. Eventually, by 1938, the first Set

Complete Radio (or Signal Corps Radio, as it is usually but incorrectly

called) was rolled out. This unit, dubbed the SCR-268, was able to aim

searchlights associated with anti-aircraft guns, but little else.

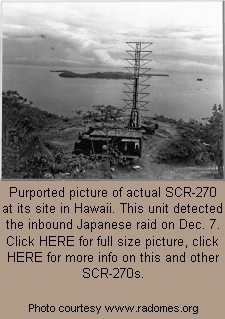

But

that was just the beginning. Once this trick had been mastered it was just a

matter of time before the U.S. Army Signal Corps brought to market the tools

the other combat arms needed during WWII. With rapidity the SCR-268 morphed

into the SCR-270, which, built by Westinghouse, began to make its appearance

at Army bases in 1940. As we all know, an SCR-270 was in full operation near

the island of Oahu on the morning of December 7, 1941. At 0720 its Signal

Corps operators detected and reported a flight of planes heading due north;

and we all know what happened next. By 0759 the Japanese were enjoying a

site seeing tour over a bombed out Pearl Harbor.

But

that was just the beginning. Once this trick had been mastered it was just a

matter of time before the U.S. Army Signal Corps brought to market the tools

the other combat arms needed during WWII. With rapidity the SCR-268 morphed

into the SCR-270, which, built by Westinghouse, began to make its appearance

at Army bases in 1940. As we all know, an SCR-270 was in full operation near

the island of Oahu on the morning of December 7, 1941. At 0720 its Signal

Corps operators detected and reported a flight of planes heading due north;

and we all know what happened next. By 0759 the Japanese were enjoying a

site seeing tour over a bombed out Pearl Harbor.

The 270 was replaced by the 271, which was upgraded to

the 518 which provided radar altimeter data for the Signal Corps'

controlled Air Force. This technology was then expanded to include the

SCS-51 which offered the first viable version of instrument landing

assistance… a concept and technology that the world’s airline industry could

not exist without today. All pause now… thank you U.S. Army Signal Corps for

the modern American airline system! [Editor’s note: the Signal Corps’

development of the ability to land aircraft in bad weather can not in any

way be blamed for today’s trend to strip search you when you want to fly on

one of these aircraft. You will have to blame someone else for that mess.

Try the TSA.)

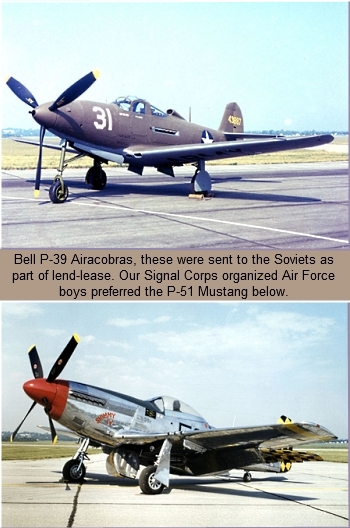

In 1941 the research labs at Ft. Monmouth were

relocated a few miles south to Camp Evans, in a building known as the

Marconi Hotel (not an actual hotel folks… it was just called that). By

mid-1940 the research being done by the Signal Corps began to be shared with

our British counterparts and this led to even faster technology

development. When the secret stuff the Brits were working on arrived at the

Marconi Hotel development took off almost as fast as one of the new North

American P-51 Mustangs (1940), or perhaps the Bell P-39 Airacobras [1941,

an aircraft sent in mass to the Soviets as part of lend lease… which shows you what the

Signal Corps' new Air Force branch thought of it].

After

the mess at Pearl Harbor the Signal Corps got into true high gear, working

around the clock and at a fevered pitch to develop systems able to protect

the Panama Canal from a similar fate. Microwave was abandoned as the

frequency of choice as frequencies in the 600 MHZ range were tried. Using

four triodes and their associated circuitry, tightly packaged into one glass

envelope, the Signal Corps was able to produce over 240-kW pulse-power at up

to 600 MHz.

After

the mess at Pearl Harbor the Signal Corps got into true high gear, working

around the clock and at a fevered pitch to develop systems able to protect

the Panama Canal from a similar fate. Microwave was abandoned as the

frequency of choice as frequencies in the 600 MHZ range were tried. Using

four triodes and their associated circuitry, tightly packaged into one glass

envelope, the Signal Corps was able to produce over 240-kW pulse-power at up

to 600 MHz.

At about this point in time the numbering system used

to designate communication systems seemed to go awry, at least from where we

sit here in 2012. From the simple SCR 1, 2, 3, 4… etc numbering scheme

things jumped to AN/TPS, TQL, CPS, VCS, and on and on. Regardless,

development progressed and brought to the field the communication systems

needed to achieve the earlier stated goals of capacity, speed, and

precision.

All in all the task of finding a better way of passing

information around the battlefield and back and forth between headquarters

was conquered by the Signal Corps, at first slowly perhaps, but by the time

of Pearl Harbor and after at full speed. As an exercise in corporate

development… development being run and managed by an arm of the U.S.

government, it boggles the imagination as to why this same feat cannot be

accomplished today. With little doubt, today the U.S. government is unable

to match corporate America when it comes to efficiency, low cost of

operations and effectiveness of purpose… with the military having nominally

abandoned their responsibilities for developing technology in entirety. Yet

the U.S. Army Signal Corps did it back then.

Back during WWII though there was no other option. The

task of finding a better way to communicate such that America could win the

war it found itself in fell to the Signal Corps. Technologically speaking

the distance from visual signals to RADAR was vast; yet both forms shared a

basic functional need: pass information that was accurate, reliable, rapidly

available, and able to be internalized by the participants.

What we see here then is not just the transformation of

technology from a nice-to-have accoutrement to life, or a useful tool to

help win battles, but the simultaneous transformation of the institution

that enabled that transformation to take place: the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

This transformation, which began in earnest in the

1940's, led to the Signal Corps we know today. Embracing everything from the

aforementioned electronic forms to still pictures, training films, combat

newsreels, archiving, and much more: the Signal Corps pushed the envelope of

what was considered “communication.” Without the Signal Corps redefining,

back during the early days of the second world war, what communication

encompassed many of these areas might never have received any formal

attempt to develop them, or have been left to the whim of history for their

progression. Instead, back in the 40s the Signal Corps took a holistic view

of what was involved when people communicated and expanded its purview to

encompass it.

As an example, if it weren’t for the Signal Corps the

concept of “counter-communication” would have been left out of the equation…

at least until a much later point in time, post-WWII, when some devious

political hack would have discovered it. Instead, in early 1941, the Signal

Corps recognized the value of disinformation and "spin" to the communication process

and set about developing means and methods for the interruption, obscuring,

or obstruction of what we might think of as “normal” communication. Because

of this hardware elements like chaff were invented, as were "cigars" and

"carpet," devices that were very effective in jamming enemy RADAR. Speech

scrambling received attention too, as can be attested to by the excellent

articles penned by our own Don Mehl, OCS Class 44-35, who has written and

published on this website numerous articles on the

SIGSALY (Green Hornet) and SIGTOT communication systems. The

Signal Corps recognized early the value of being able to not only obscure

our own communications but also both hinder and intercept telephone or

other forms of communication coming from the enemy. In every way, from

monitoring and interception to all modes of cryptography the Signal Corps

stepped forward, embraced the need to control the communication process, and

assured that on our side of the war we held in our hands the best means of

communication available.

Whether used for simple or complex signaling, natural

or artificial, supportive or disruptive, or serving single or multiple

functions, the concept of passing information became an obsession for the

men and women that led the Signal Corps during WWII. The mission must be

accomplished at all cost... and it was.

But a price had to be paid for this determination to

control and alter the future: the Signal Corps itself had to change.

The Place of the Signal Corps

Principally speaking, the tasks the Signal Corps needed

to accomplish to help America win WWII needed to be done not by pursuing

science for the sake of science, but through practical experimentation, with

that pursuit taking place

primarily in the areas involving electrical mechanics. This requirement that

the U.S. military change the structure of the Signal Corps so that it could

master and employ electrical mechanics caused the new WWII Signal Corps to move ever

so slightly away from being just a combat arm to also becoming a member of what

were then called the technical services. The net result was that for the

majority of World War II the Signal Corps was thought of by those at the top

as one of the seven technical services. For those of us who served through

the Korean and Vietnam wars this helps explain the confusion we felt, and

those “other” soldiers to whose units we were attached, as they wondered what

exactly a Signaleer was. Were we one of them, or not?

The concept of classifying the Signal Corps as a

technical service was significant as the term implied that the corps was

focused not on field duty in combat but on the use and application of

applied sciences. Up until this time the idea of the Signal Corps being some

sort of group of eggheads was unheard of. Before World War II the Signal

Corps was considered a combat arm, something that began at its inception in

the Civil War. Now, with the onset of WWII, it was finding itself being

tossed into the mix with the six other technical services, with folks looking

at it as an agency of the Services of Supply instead of a member of the Army

Service Forces. For many field Signal Corps Officers who were still not only

ducking bullets in the field but actively engaging in combat in order to

get the message through this simply would not do.

Structurally, in WWII, the entity known as the Army

Service Force comprised one of three major groupings of resources of men and

matériel. The other two were the Army Ground Forces and the Army Air Forces.

As originally envisioned, the Army Air, Ground, and Service Forces were

intended to be both interdependent as well as independent. With Signal Corps

Officers fighting the idea of being reclassified as a service force, thus

losing the combat designation they had held pride in since the Civil War,

the question was how to handle the changes that demanded that the Signal

Corps be free to advance technology as it wished, but still make it

accountable for the results of its work, as that work was deployed in the

field. In basic terms, the problem was where should the Signal Corps be

placed in this group of three: Army Service Forces, Ground Forces, and Air

Force.[3]

While some might say that the answer should have been

to define a fourth classification, the truth was that it was easier at the

time to simply concede to the obviousness of the fact that Signal Corps

Officers (and troops) were in daily combat in the field, working to assure

that what was needed to be heard and transmitted was in fact heard and

transmitted. In other words, the WWII leaders at the time decided that

bigger problems needed to be solved than whether the evolving Signal Corps

was a combat arm or not and therefore defined the Signal Corps as being two

services in one, which of course made everyone happy. The result was that although administratively the Signal

Corps was designated to serve as a component of the Army Service Forces, its

equipment, functions, and trained men were brought to the field via either

the Ground or Air Force services. For most of us, even up to the time of the

Vietnam War, this held true in theaters of war as well as defense and base

commands.

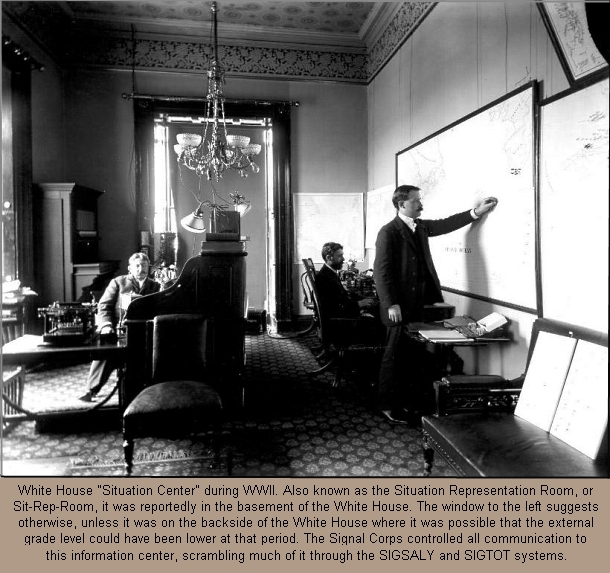

So what was the Signal Corps during WWII, and how

should it be thought of today? Perhaps the best way to answer that question is to

see it as

working to integrate every element of military communication and every user

of each form of communication, from the President (for whom the Signal Corps

provided communication links to the then called Situation Representation

Room in the basement of the White House), to the Secretary of War, the

Chiefs of Staff, the General and Special Staffs who ruled over theaters,

task forces, defense and base commands, the Army Ground, Air, and Service

Forces, all the way down to the subdivisions that controlled ground and air

arms and services. In other words, while at the beginning of WWII it might

not have started out so, by the end of the second world war the Signal Corps handled all of these and more.

Even today it looks, smells and tastes

much the same.

So what was the Signal Corps during WWII, and how

should it be thought of today? Perhaps the best way to answer that question is to

see it as

working to integrate every element of military communication and every user

of each form of communication, from the President (for whom the Signal Corps

provided communication links to the then called Situation Representation

Room in the basement of the White House), to the Secretary of War, the

Chiefs of Staff, the General and Special Staffs who ruled over theaters,

task forces, defense and base commands, the Army Ground, Air, and Service

Forces, all the way down to the subdivisions that controlled ground and air

arms and services. In other words, while at the beginning of WWII it might

not have started out so, by the end of the second world war the Signal Corps handled all of these and more.

Even today it looks, smells and tastes

much the same.

Today, in part because of its involvement in cyber

security and intelligence gathering and dissemination the Signal Corps

spends as much time managing key aspects of the multiplicity of army groups,

armies, corps, divisions, regiments, battalions, companies, and platoons

within which it has communication responsibilities as it does its own

functions. It also spends an inordinate amount of time thinking of the

future and planning for it, in terms of where communication is going and how

the Signal Corps can help the U.S. military achieve swift, strong,

adaptable, simple, and secure communication. Finally, it also spends a

sigificant amount of time liaising with sister agencies in the

various Air Force and Navy commands, sometimes down to the unusually

granular level of things such as Air Force wings, groups, squadrons, flights, administrative divisions, branches, sections, subsections, and on

and on.

The point in all of this is that while originally the

thought was that the Signal Corps should be little more than an arm of the

combat service it

actually needed to provide a service akin to an overarching arm of the DoD

itself. The work the Signal Corps did during WWII began a movement in this

direction, with that movement accelerating throughout the Korean and Vietnam

Wars until today. In modern corporate

speak, since WWII it has been found that the Signal Corps needed to be

able to act as everything from the military's IT Department to its IS, CIS,

MIS, CS, and EE experts, providing both hardware, software, services, and management

expertise throughout all of the “customer facing” areas and interface points

the military has.

The point in all of this is that while originally the

thought was that the Signal Corps should be little more than an arm of the

combat service it

actually needed to provide a service akin to an overarching arm of the DoD

itself. The work the Signal Corps did during WWII began a movement in this

direction, with that movement accelerating throughout the Korean and Vietnam

Wars until today. In modern corporate

speak, since WWII it has been found that the Signal Corps needed to be

able to act as everything from the military's IT Department to its IS, CIS,

MIS, CS, and EE experts, providing both hardware, software, services, and management

expertise throughout all of the “customer facing” areas and interface points

the military has.

For those not familiar with the term "customer facing," it is worth a

moment to note what comprises the customer facing aspects of today's

military. In this context, customer facing means that area of the military that supports

and services the “stakeholders” that must be dealt with

in order to achieve the military's communication goals. Thus a customer

facing interface point marks that specific locus where Signal Corps

personnel and/or equipment come face to face with one of the Signal Corps'

stakeholders, as it attempts to meet that stakeholder's needs.

In terms of who these stakeholders are, flitting here

between the business world and the military world, we can say that such stakeholders extend far beyond

customers (in military speak, think: the citizens of the country you are fighting

for) to include shareholders (the people who provide the money you need in

order for you to do your job… e.g. Congress); to the employees (members of

the Signal Corps itself); third party customers (your allies in war); suppliers

(everyone from the Navy, Coast Guard or Air Force that may provide a service

to you or depend on a service you provide); to the companies that make your

equipment; the allied countries and militaries that help feed, clothe and

house you; communities (e.g. external parties that train your people,

provide protection [e.g. Blackwater]); commercial organizations (e.g. those

who assure that your equipment arrives on time); to all manner of remotely

associated entities from suppliers to third party governments and

regulatory agencies, legislative bodies, industry trade groups, professional

associations, NGOs, advocacy groups, prospective recruits, local

communities, the public at large, competitors, analysts and the media,

alumni, research centers, and of course the future generations whose life

and liberty Signal Corps efforts are trying to ensure. It's a long list,

these stakeholders whose needs the Signal Corps is trying to meet.

Finally, it should not be missed that because it has

integrated itself so completely throughout every aspect of the military's

operation, the U.S.

Army Signal Corps is homogonously the jugular of the military. If it gets cut, the war

effort stops. Signaling comprises an indisputable operational need; without

it the U.S. military's eyes and ears cease to be of value and its mind is

without substance to parse.

Which brings us to our conclusion, as a nation we owe a

debt of gratitude to those rare military leaders of WWII who recognized the

need for the

Signal Corps to embark on a major transition, moving the unit away from its

then traditional role towards one which would support the U.S. military well

into the 21st century and beyond. Single handedly they defined a set of new

responsibilities for the Signal Corps, tasks that took the Corps from a support arm with vague

capabilities and capacities developed during World War I to becoming a crucial part of the

WWII war

effort and every war since then.

Our debt of gratitude must also extend to

those WWII Signal Corps Officers who recognized the new role they needed to play, and

both re-dedicated and redoubled their own efforts towards assuring that the Signal Corps

acquired and mastered the capabilities it needed in order to meet the

nation's needs… from developing new forms of communication to managing

their supply to the field, training and staffing in their use, and assuring

that those who needed these systems most had ready, responsive and timely

access to them, along with well trained operators who could see to it that

these systems worked. If you want to know the names of these Officers,

you'll find the bulk of them listed

here. We salute them all.

Footnotes

[1] For more information on Moore's Law, please click here

)

- To

return to your place in the text click here:

)

- To

return to your place in the text click here:

[2] Radiosonde: a radio probe able to read barometric

pressure and other data at altitude and transmit it back to a fixed receiver

on the ground. Today radiosondes measure pressure, altitude, geographical

position (latitude and longitude), temperature, relative humidity, wind

speed, wind direction, and cosmic ray levels. Radiosondes that measure ozone

concentrations are known as ozonesondes.

- To

return to your place in the text click here:

[3] The Army Ground Forces drew in the Infantry, Cavalry,

Field Artillery, Coast Artillery Corps, Armored Force, Antiaircraft Command,

and Tank Destroyer Command. - To

return to your place in the text click here:

Additional Sources

Thompson, R.L. (1947). Wiring a continent: A history of the telegraph

industry in the USA, 1832-1886. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Rivise, M.J. (1950). Inside Western Union. New York: Sterling

Publishing Company.

WD, Introduction to Employment in the War Department—A Reference Manual

for Employees, Aug 1942, p. 21.

- - - -

Have a comment on this article? Send it to us. If you

are a member of the Association we will gladly publish it. If you are not,

well, it only costs $30.00 a year to become a member and have your views

heard... and because we are a fully compliant non-profit organization your

payment is tax deductable. If you would rather not become a member a $30.00

donation to our

Scholarship Fund will accomplish the same, and we

will gladly publish your views on this article.