This article originally published on our Home Page in March 2012.

Hey! That's My Money!

In this time of everyone

speaking out about America having set in place too many entitlement programs

for its own good, few would complain about people receiving entitlements

that they paid for out of their own pocket. Social Security comes to mind as

one of these. It makes little sense to complain about people receiving

Social Security payments after they retire, when you consider that the money

they are receiving was previously deducted from their paycheck… all of their

lives… in every job they held… for every paycheck they ever received… until

the day they retired… and even after that if they continued to work on a

part time basis. Their right to receive these funds, post-retirement, is

clear and inviolable, especially when you consider that the government held

all of that money in trust for the payer during all of those years,

supposedly investing it over and over again down through time, so that the

beneficiary would have it and its accrued interest available for their use

once they got too old to work.

The same is true for military retirement benefits,

as when you get right down to the facts the retired military personnel who

receive these benefits paid for them out of their pockets during all of the

years they served. Whether based on deductions or some other formula,

military personnel have a right to receive their money back after they

retire because the funds involved came out of the soldier’s pocket during

all of the years he served. As an example, consider the average military

Officer who during his years in service had an annual income equal to only

30–40% of what an equivalent executive would have made in private business.

Who benefited from this cut in pay for 30 years of service? Clearly, the

U.S. government. They got to use the money they saved by paying military

personnel less than their civilian counterparts for all of those years that

the serviceman worked. In return, they agreed to pay a retirement benefit to

the Officer at the end of his career.

When viewed this way, it’s easy to see that a

military Officer is paying for his future retirement benefits every year

that he continues to willingly work for a lower income and let the

government have the rest. Part and parcel of why people serve… this

willingness to give so much of one’s earning potential over to the

government for their own use is no less heroic or significant than the

Officer or Enlisted Man’s willingness to sacrifice his own life for his

country. Clearly, the funds that these people earned from the years that

they served, but let the government keep and manage on their behalf, are

rightfully theirs. And as such each such person should be entitled to

receive these funds back, along with the interest they earned, when they

retire.

So how are you doing with your benefits? Are you

getting them on time?

Then you’re lucky, as some Officers have had to

really struggle to get theirs. Some Officers far more important to

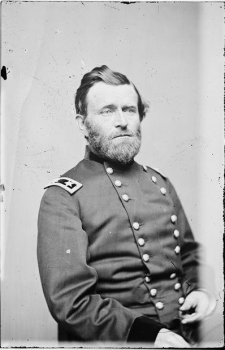

America than any of us Officers ever were. Some... like Ulysses S. Grant.

Yes,

that’s right. Mortally ill, dying from cancer, on the verge of bankruptcy,

and battling everyone from debtors to reporters, towards the end of his life

Grant was in trouble and desperately needed money to keep himself and his

family above water. Once granted to him, Grant lost his military retirement

benefits in a strange way. A technicality related to his transition from

General to President caused him to lose them… and while at the time he

didn’t consider it important, by the time he retired this minor technicality

ended up having a profound affect on his life.

Yes,

that’s right. Mortally ill, dying from cancer, on the verge of bankruptcy,

and battling everyone from debtors to reporters, towards the end of his life

Grant was in trouble and desperately needed money to keep himself and his

family above water. Once granted to him, Grant lost his military retirement

benefits in a strange way. A technicality related to his transition from

General to President caused him to lose them… and while at the time he

didn’t consider it important, by the time he retired this minor technicality

ended up having a profound affect on his life.

Let us tell you the story.

First, let’s consider again how important Grant

was to America. From the time of America’s revolution until the Civil War

there were no Generals of the Army other than Washington and Grant. In other

words, after Washington some 90 years passed before Grant was appointed to

the position of General of the Army, in 1866 (Winfield Scott, appointed in

1855, was a Brevet Lieutenant General, not a General of the Army). The

reason for this was that after Washington, the position of General was

considered an office of a special nature. Back then, it was not part of the

standard ranks of military Officers. Instead it was only conferrable by a

unique Act of Congress, and upon a person specifically named in that Act.

Army Signal OCS graduates will recognize this as the forerunner and

beginning of the tradition that caused us, when we were newly appointed as

commissioned Second Lieutenants, to be so appointed by an Act of Congress

that made each us “an Officer and a Gentleman of the United States of

America.” Unlike in other countries, in America one could not inherit the

rank of General, nor succeed to it by promotion from a lower ranking station

when the position became vacant. And so when Washington passed from the

scene the position went unfilled.

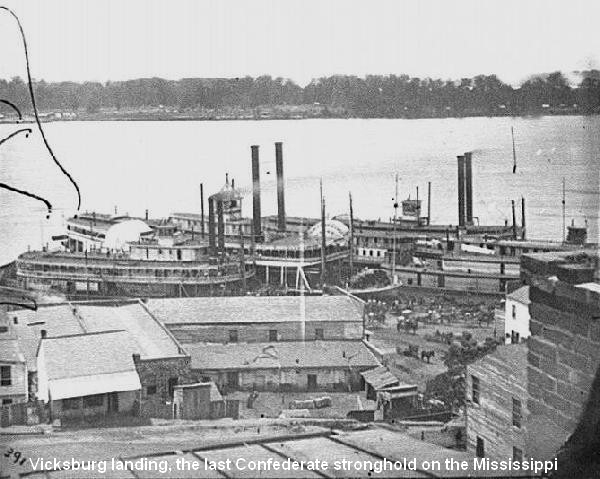

Grant earned his way

to Congressional appointment in the position of General by his impressive

victories. The first that brought him to the President’s and Congress’

attention was Vicksburg, in July 1863. As part of his Vicksburg campaign

Grant moved his HQ to Chattanooga and from their set out in full force after

the Confederate army. In what we all recognize

as

a series of brilliant actions, he lifted the siege, chased the Confederates

into the countryside, and then from there forced them all the way back to

Georgia. Congress was so grateful for his having turned the tide in the war

that they struck a medal for him, and at the same time revived the rank of

Lieutenant General and appointed him to it.

as

a series of brilliant actions, he lifted the siege, chased the Confederates

into the countryside, and then from there forced them all the way back to

Georgia. Congress was so grateful for his having turned the tide in the war

that they struck a medal for him, and at the same time revived the rank of

Lieutenant General and appointed him to it.

Clearly, Grant deserved the

appointment, as he had up to that point won some 17 battles, imprisoned over

150,000 Confederate soldiers, opened up the Mississippi River for Union

traffic, and cleared the entire state of Tennessee. In simple terms: he set

the Civil War game board up for a final Union victory.

When he achieved his rank of Lieutenant General he

received along with it a pension that Congress granted to him… provided of

course that he stayed in the Army and served until his retirement… and then

went into retirement as a reserve Officer.

Few could have imagined that instead of retiring

Grant would end up running for President. And, of course, since at that time

an individual could not be an active Officer in the Army at the same time

that they were running for President, Grant ended up resigning his rank.

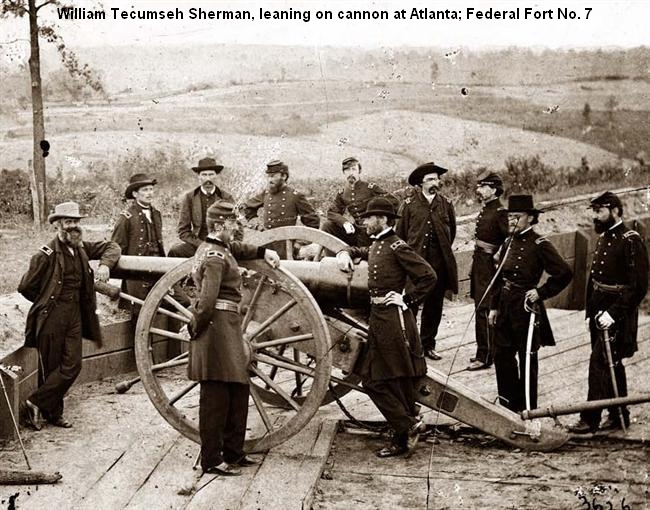

While

few, including Grant, thought anything of this simple act, on the sidelines

a close friend of Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman was watching and noticed

this little slip. He immediately knew that by resigning his rank instead of

simply retiring, Grant would be barred from being able to collect his

pension.

While

few, including Grant, thought anything of this simple act, on the sidelines

a close friend of Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman was watching and noticed

this little slip. He immediately knew that by resigning his rank instead of

simply retiring, Grant would be barred from being able to collect his

pension.

Students of history will know that Grant went on

to serve as President, being elected by a landslide in 1868. In 1872 he was

again elected to a second term. After his second term, as a successful man

and modestly wealthy, Grant spent two years touring the world with his

family, after which he then returned and entered into business in New York

City.

The qualities that Grant brought to Generalship

did not transfer well to business. The firm he became associated with was

named Grant & Ward, and was considered one of the darlings of Wall Street.

Unfortunately, it overextended itself, practiced dubitable activities, and

the Ward half of Grant & Ward even went about mismanaging the funds the firm

received, to the point of illegality. On May 4, 1884, the firm collapsed

into bankruptcy.

Subsequent investigations, both then as well as

down through the ages, have shown that Ulysses S. Grant neither knew

anything of nor was involved in any of the illegal activities of Grant &

Ward. Grant’s partner Ward was the guilty party. Within a few months of the

firms collapse he was arrested, charged with fraud, and found guilty. He

spent 6 years in prison for his efforts.

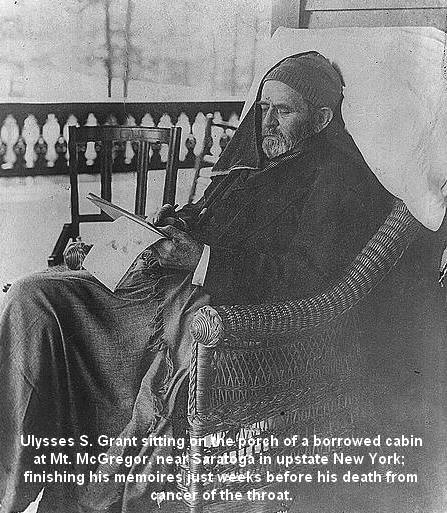

Grant

in the mean time suddenly found himself penniless, embarrassed, and

suffering from both a wounded pride as well as a growing cancer of the

throat that would end up killing him within 15 months.

Grant

in the mean time suddenly found himself penniless, embarrassed, and

suffering from both a wounded pride as well as a growing cancer of the

throat that would end up killing him within 15 months.

It cannot be said too finely, Grant was in real

trouble. The Homeric-like heroic life of the man that (with apologies to

Abraham Lincoln) single handedly saved the Union, had gone from the

proverbial hero to zero literally overnight. Sick, on the edge of dying,

Grant had absolutely no way of supporting his wife after his death, nor

paying for their cost of living while he was still alive.

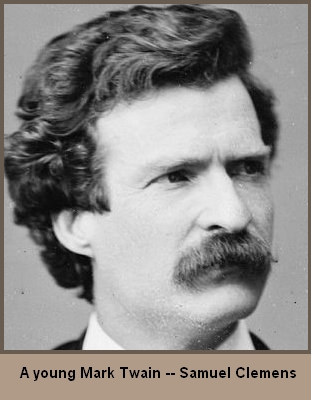

Almost at the very last minute two people came to

his rescue. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) befriended Grant and both encouraged

and worked with him to help him capture his remembrances and pull his

memoires together for publication. Because Clemens knew a bit or two about

publishing, he was able to promise Grant that if he managed to succeed in

writing his memoires before he died, Clemens would be able to get them

published, market them, and collect enough royalties in the process to pay

to either Grant or his wife at least $200,000. True to his word, Twain saw

to it that Grant’s memoires were published, and that all of its royalties

were paid… to the extent of over $450,000 being paid after Grant’s death to

his wife Julia.

William Tecumseh Sherman, a man whose caricature

fit his character to a tee, watched this whole scenario play out. And while

he hoped that Twain would succeed, he realized that if Grant died before his

memoires were in publishable form, he would die in penury. Sherman, with a

pockmarked face, never seen smiling, ramrod straight, disciplined, direct,

forceful, remote, with a voluble temper, and plagued by self-doubt, was

nevertheless beyond true to his friends. An old West Point classmate of

Grant’s, Sherman thought that it was a shame that the U.S. government wasn’t

coming to the aid of this most important of America’s heroes.

To

help change things, Sherman, who was quite vocal about his dislike for

politicians, set about personally lobbying the House of Representatives to

reinstate Grant’s military pension. While he put his all into it, somehow

Congress was simply too preoccupied with other matters to consider the

financial health of a great General who was literally on his death bed.

Then, when it finally did decide to consider the matter, it found itself in

a situation where it was forced to go into recess and not address the

matter, because of the requirement that Congress could not be in session

during the inauguration of a new President (Grover Cleveland). This set up a

problem, because if Congress was not able to act before it went into recess,

it would likely never act, as a new Congress would be seated, and by the

time it would get around to acting Grant would be dead.

To

help change things, Sherman, who was quite vocal about his dislike for

politicians, set about personally lobbying the House of Representatives to

reinstate Grant’s military pension. While he put his all into it, somehow

Congress was simply too preoccupied with other matters to consider the

financial health of a great General who was literally on his death bed.

Then, when it finally did decide to consider the matter, it found itself in

a situation where it was forced to go into recess and not address the

matter, because of the requirement that Congress could not be in session

during the inauguration of a new President (Grover Cleveland). This set up a

problem, because if Congress was not able to act before it went into recess,

it would likely never act, as a new Congress would be seated, and by the

time it would get around to acting Grant would be dead.

Sherman, frustrated and angry at the incompetence

and lack of principles of the congressmen he met, mounted a frontal charge

against the senators and representatives involved, just as he had done at

Shiloh. Twisting elbows and letting his temper run, he manhandled

congressmen into their chambers and pushed Samuel J. Randall, the Democratic

Speaker of the House, to reintroduce the bill (Grant—S. 2530) that had been

set aside, but this time for a vote.

Even

so, things did not move fast enough and at the end of the day on March 3,

1885, the House recessed without having considered the matter. The next day,

March 4, was to be the inauguration day for the new President, Grover

Cleveland, and with Congress in recess Sherman was sure all had been lost.

Even

so, things did not move fast enough and at the end of the day on March 3,

1885, the House recessed without having considered the matter. The next day,

March 4, was to be the inauguration day for the new President, Grover

Cleveland, and with Congress in recess Sherman was sure all had been lost.

But that wasn’t the end. Having made Sherman a

promise that he would do his best to get Grant a pension, on the day of

Grover Cleveland’s inauguration, with Sherman pushing from the background,

Randall reconvened the House and ordered the clerk to date all business that

might be transacted that day as having been done on the previous day, March

3. With little consideration for the gathering crowd getting ready for the

inauguration at noon, Randall ran around the Capital buttonholing

representatives wherever he could find them, dragging them back into the

chamber for a vote.

Quickly moving the House through its parliamentary

paces, and using the power that comes with being the Speaker of the House,

he garnered the votes needed to pass the bill, and set in motion an effort

to hold a vote. However, before a vote could be taken a challenge was

mounted by a Republican claiming that the bill could not be considered until

a prior matter was dealt with (an election dispute from Iowa that caused the

Iowa Republican representative to claim that he was the rightful winner and

not the Democrat that had been certified by the State).

Randall thought all was lost, as did Sherman.

Amazingly, the Republican who had not been certified (James Wilson) rose and

announced that he would withdraw his objection to the Iowa election result

if the House would immediately move to consider Grant’s bill. In

effect, he was turning his seat over to the Democrat who had been certified

instead of himself, in order to gain a pension for someone he considered an

American icon.

His

announcement was met with astonished silence by the congressmen assembled.

No one had ever seen such a gesture. Within a few seconds all present jumped

to their feet and began to applaud. Applause broke out throughout the

chamber and carried on for minute after minute. And yet while this salute to

their compatriot raised good cheer and respect, as it carried on, so did the

clock’s tick. Cleveland’s inauguration was scheduled for noon, sharp… and if

the vote was not over and certified by then, Grant’s bill would fail to

pass.

His

announcement was met with astonished silence by the congressmen assembled.

No one had ever seen such a gesture. Within a few seconds all present jumped

to their feet and began to applaud. Applause broke out throughout the

chamber and carried on for minute after minute. And yet while this salute to

their compatriot raised good cheer and respect, as it carried on, so did the

clock’s tick. Cleveland’s inauguration was scheduled for noon, sharp… and if

the vote was not over and certified by then, Grant’s bill would fail to

pass.

As the noise in the chamber continued, the clock

moved to within a minute or two of noon. A clerk, recognizing that all of

Randall’s efforts were about to be for naught, ran from the front of the

chamber to a side closet, gathered a ladder, set it up against the clock

wall, climbed to the clock, and set it back twenty minutes.

With moments to spare, everyone returned to their

seats, the vote was taken, and was found in Grant’s favor. Seconds after the

last name was called and the vote received, the clock began striking noon.

Quickly, Chester A. Arthur, the outgoing President, as well as Samuel J.

Randall, the outgoing Speaker, pushed the representatives from the chamber

out onto the inauguration platform and Grover Cleveland was sworn in. While

the world watched, Cleveland became President of the United States, 20

minutes later than he should have been.

News reached Grant at his home in New York City in

the early afternoon on that same day. With a smile on his face, as a newly

reinstated Officer of the U.S. Army, he turned to his wife Julia and said

simply “I am grateful the thing has passed.” She smiled back at him and said

“Hurrah, our old commander is back.”

As for Sherman, while few would recognize it as

such, this battle was won just like all the others he commanded… with sheer

guts, determination, and no quarter being given to the enemy.

The next morning Grover

Cleveland made the reinstatement official by signing Grant’s commission. As

a reinstated Lieutenant General, Ulysses S. Grant earned a salary of $14,500

each year, with his wife being provided an additional $5,000 a year. Best of

all, because the reinstatement was made retroactive to the date on which

Sherman first petitioned for it, nearly a year earlier, Grant was able to

receive back pay that held him and his wife financially secure until his

death on July 23, merely four and a half months after the vote.

Sources used in the writing of this article

include:

Grant and Twain; by Mark

Perry, Random House, 2004.

Memoires of William Tecumseh Sherman; New York,

Library of America, 1999.

The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant; John

Y. Simon, ed., New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1975.

Grant In Peace, from Appomattox to Mount McGregor: A

Personal Memoire; Badeu, Adam; 1881

(Hartford: D. Appleton).