The war in Vietnam did not

get up to speed as rapidly as some might think…

combat wise things got off to a slow start. Up

until 1965 combat operations just sort of bumped

along. But around about the end of 1965 it all

began to change, as more and more units began

arriving in country, with their commanders

anxious to get it on.

To be more specific, America's

military involvement in Vietnam began with advisors sent to

assist Ngo Ding Diem’s rookie army in 1954. Between 1961 and

1964 their number grew from 900 to 23,000. Yet while the

number was significant, the involvement of these advisors

was minimal, being relegated to a narrowly defined

instructional and training role. It wasn’t until February

1965 that the U.S.' first independent combat operation was

mounted in what would become known as the Vietnam War, and

that involvement centered around a series of retaliatory

strikes after the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Being what it was, no ground troops

were involved, as the strikes were carried out by the U.S.

Air Force and Navy. Strange as it was however, neither this

independent action on the part of the U.S. to escalate the

war, nor a decision made in February of 1965 to increase the number of

ground troops in-country by sending 3,500 Marines to Đà Nẵng, was shared with the South

Vietnamese government. Except for a trifling last minute

request to the South Vietnamese Premier Dr. Quat the morning

of the Marine's actual arrival on the beach—to issue a press statement supporting the

U.S.’ efforts—the South Vietnamese were kept in the dark

until it was too late for them to do anything about it.

Instead, miraculously, the Marine's amphibious assault craft

simply appeared on the horizon, world press just as

miraculously appeared on the beach, as did dozens of pretty

young Vietnamese girls dressed in áo dàis,

ready to drape the advancing Marines with leis. Does anyone

sense an ego at work here?.[1]

That

was the case for the 3,500 Marines

that landed at Đà Nẵng on March 8, 1965... and it was also

the case for the 20,000 support

personnel that were ordered to Vietnam on April 1, 1965, as

well as

the order issued on April 14 to deploy the entire 173rd Airborne

Brigade. For a war that was supposed to be about Uncle Sam

working hand in hand with the South Vietnamese government to gain control of the country,

upgrade the skills of the ARVN, help the ARVN oust the NVA and V.C.,

and set up a democratic system of government,

Westmoreland sure was keeping his "partner" in the dark

about his intentions.

That

was the case for the 3,500 Marines

that landed at Đà Nẵng on March 8, 1965... and it was also

the case for the 20,000 support

personnel that were ordered to Vietnam on April 1, 1965, as

well as

the order issued on April 14 to deploy the entire 173rd Airborne

Brigade. For a war that was supposed to be about Uncle Sam

working hand in hand with the South Vietnamese government to gain control of the country,

upgrade the skills of the ARVN, help the ARVN oust the NVA and V.C.,

and set up a democratic system of government,

Westmoreland sure was keeping his "partner" in the dark

about his intentions.

One wonders, if the government and

military of

South Vietnam... even in those early days... had a greater involvement in planning and

prosecuting the war, or at least understanding the logic

behind America's actions, might they not have been able to

go it alone when the time came? And if not... that is, if it

was not possible for the South Vietnamese ever to go it

alone... then what were we doing there in the first place?

Was the plan to stay forever? No? Then why wasn't the South

Vietnamese government and its military brought into the

equation day one and taught what they needed to know to run

their own country... including the knowledge that we

weren't going to stay forever and that they had better

get on about building both a democratic country and a

military that could defend it, instead of wasting their time

fighting internecine political wars for power while we

pursued Charlie in the boonies?

To this author it's amazing the

stupidity with which America fights its modern day wars to

free nations. Yes, it's o.k. to send our men into battle to

help free the people of another country... but if we are

going to do so then we should demand that the leaders of

that country step up to the task of creating both a

functioning government and a capable military. If the

leaders they pick don't prove up to the task, then we should

pluck them from power and tell the people of the country to

pick another one... and keep doing this until some local

George Washington steps forward and shows that he

understands his role is to be that country's George

Washington, not its Napolean.

Regardless, as the summer of 1966

approached things really began to “hot up.” By

August five new major combat units had arrived

in country, and with their arrival serious

combat operations got underway. Technically,

1966 represented the second year of serious

combat for the U.S. Army, but in reality it was

the first year when the Army had enough men and

materials to mount a vigorous, forceful,

coordinated effort. So in 1966 the war began in

earnest, and with it the Signal Corps was put to

the test.

Since most of the training

of the newly arrived Signal units had occurred

in Europe or the U.S., where methods of

communication between combat units had already

been codified into a science for some 20+ years,

it came as a surprise to those setting up the

systems in 'Nam that these same approaches to

the use and application of communication

technology were not operating as expected.

Instead, rather than finding that their deployed

gear worked swimmingly, what they found was that

things that had worked back home simply didn’t

work in Vietnam.

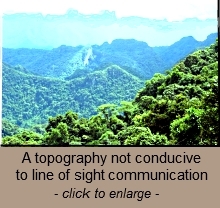

One of the reasons, as

they quickly learned, was that while the terrain

back home and in Europe was benign and conducive

to the kind of communication architectures and

equipment the Army employed at that time,

Vietnam was proving to be different. More to the

point, what they found was that whether because

of the unique tactical scenario the enemy

presented in Vietnam, or the climatic and

geographic conditions that existed, getting

reliable communication up and running was not

only proving difficult but often times

impossible. Overall, getting communication links

in place to support tactical combat field

operations was turning out to be a real problem

for the Signal Corps in the early days of 1966.

One of the reasons, as

they quickly learned, was that while the terrain

back home and in Europe was benign and conducive

to the kind of communication architectures and

equipment the Army employed at that time,

Vietnam was proving to be different. More to the

point, what they found was that whether because

of the unique tactical scenario the enemy

presented in Vietnam, or the climatic and

geographic conditions that existed, getting

reliable communication up and running was not

only proving difficult but often times

impossible. Overall, getting communication links

in place to support tactical combat field

operations was turning out to be a real problem

for the Signal Corps in the early days of 1966.

To make matters worse,

while many units, like the 25th Infantry

Division, had trained for jungle operations in

climates similar to that of Vietnam, and had

learned something or two in the process, the

combat similarities they internalized didn’t

carry over to the Signal support personnel that

trained with them. That is, while for the

infantry boys combat simulation in a hot climate

proved to be similar to what they found in

Vietnam, this same training regimen was proving

to be of little value to the Signaleers arriving

in Vietnam. The reason was that what the combat

boys were up against was heat, while the Signal

guys were up against

something entirely

different: a topographic environment far

different than either what they had trained in

or that which their equipment was designed for.

It’s one thing to learn to take a few salt

tablets and keep yourself hydrated, it’s another

to learn how to bounce a ridge line signal over

a bunch of hills and then aspirate it through a

jungle canopy until it hit the FM radios on the

other side.

something entirely

different: a topographic environment far

different than either what they had trained in

or that which their equipment was designed for.

It’s one thing to learn to take a few salt

tablets and keep yourself hydrated, it’s another

to learn how to bounce a ridge line signal over

a bunch of hills and then aspirate it through a

jungle canopy until it hit the FM radios on the

other side.

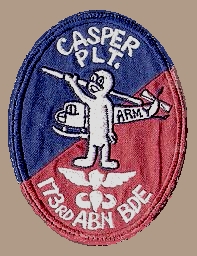

This

became evident when the first major combat

element to arrive in Vietnam, the 173rd Airborne

Brigade, discovered that it was having a devil

of a time communicating over extended distances

of any kind. In this case both local terrain

conditions and unit dispersal proved to be the

problem, for while the 173rd's troops were in

Vietnam their logistics base was in Okinawa. All

told, communication between the units HQ, their

logistics base in Okinawa, and their forward

bases in the field proved to be a bridge too far

for the signals equipment being relied on.

For

these guys, where normally voice communication

would be established around the use of the

standard single sideband radio equipment the

unit normally employed, in this new theater of

war this SOP approach was simply not working.

Paramount in this was the fact that the

distances involved were far beyond the designed

range for the assigned equipment, and even when

they weren’t the topographies involved defeated

the system’s ability to carry the signal over

the route needed. From day one then, the

Signaleers found they had to scramble to figure

out how to get voice communication up and

running.[2]

Part of the answer was

found in an expedient solution invented early in

1965, when some Signal guy somewhere mounted an

FM command and control console in a UH-1D

helicopter and took to the skies with it. This

improvised platform was then used as an airborne

relay to help get the message up and over the

obstacles involved, and the distances too, until

it reached the intended party. It proved to be

so effective that almost immediately the idea

was copied by other units throughout the

country.

Part of the answer was

found in an expedient solution invented early in

1965, when some Signal guy somewhere mounted an

FM command and control console in a UH-1D

helicopter and took to the skies with it. This

improvised platform was then used as an airborne

relay to help get the message up and over the

obstacles involved, and the distances too, until

it reached the intended party. It proved to be

so effective that almost immediately the idea

was copied by other units throughout the

country.

At the same time the

Signal Corps itself began designing a

communication system to fit in the Huey, so that

combat commanders like those just arriving could

take to the air and control their air assaults

in real time, rather than sit back in an office

somewhere in Nha Trang and try to second guess

the troops on the ground.

The first of these was

designated the AN/ASC6. It included a basic

console, two FM radios, one VHF radio, one UHF

radio, and one high frequency signal side band

radio. In essence, it tried to duplicate what

the earliest Signaleers had patched together as

an expedient to provide both airborne relay and

airborne command and control.

Historical Signal Corps documents claim that the AN/ASC6 was

brought to the field in 1965... if so, it must have been a

well kept secret as there are no contemporaneous accounts of

its use, while there are dozens of stories of kluged

airborne relay systems being built and launched by

eager, creative and driven E3 - E4 Signaleers. Instead, the

earliest accounts of it begin to pop up in early 1968, by

which time the AN/ASC10 was hitting the field, purportedly

to replace the mysterious and unaccounted for ANA/ASC6. As

for the difference between them, the AN/ASC10 provided an

internal intercom system for the command group onboard the

helicopter.

Historical Signal Corps documents claim that the AN/ASC6 was

brought to the field in 1965... if so, it must have been a

well kept secret as there are no contemporaneous accounts of

its use, while there are dozens of stories of kluged

airborne relay systems being built and launched by

eager, creative and driven E3 - E4 Signaleers. Instead, the

earliest accounts of it begin to pop up in early 1968, by

which time the AN/ASC10 was hitting the field, purportedly

to replace the mysterious and unaccounted for ANA/ASC6. As

for the difference between them, the AN/ASC10 provided an

internal intercom system for the command group onboard the

helicopter.

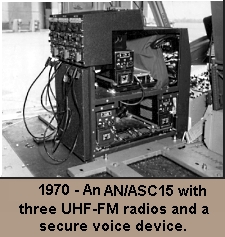

By 1968 every airborne

commander wanted his own command and control

chopper, outfitted with every radio he could get

his hands on. It was as though every LTC and above

had discovered the thrill of Ham radio. And of

course, the Signal Corps obliged, by introducing

the AN/ASC11, followed by the AN/ASC15. About

the time the war started to go flat again (1970–1971

and onward) hardly a commander of any stripe

didn't have his own little 'com center' following him around at all times.

But back in 1966 those days were still a long way off, and

the Signal guys on the ground were struggling to get basic

communications up and running.

But back in 1966 those days were still a long way off, and

the Signal guys on the ground were struggling to get basic

communications up and running.

While the kludged airborne communication relay was a step in

the right direction, and something that clearly worked, the

concept still depended on bandaged together commo equipment

that was proving to have inherent limitations. For the most

part, the limitations found stemmed from reliance on older,

WWII series FM radio sets… equipment that simply didn’t have

the horsepower needed to deal with the environment Vietnam

presented. Worse, as more and more units arrived in Vietnam

they too ran into the same problems. Within a short while it

became painfully obvious that with or without the airborne

relay concept, a more permanent solution was badly needed,

and its use needed to be turned into a standard operating

procedure quickly.

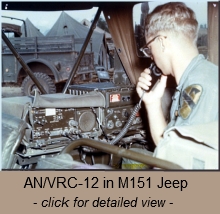

For

the 173rd Airborne Brigade part of the solution came in late

1965 when the Signal Corps replaced the older series of

radio systems the unit was using with the AN/VRC-12 family,

along with AN/PRC-25 radios. For radiotelegraphy (i.e. high

frequency radio teletypewriter service between the

battalions and brigade) two AN/VSC1 sets were made available

to each battalion, while back at brigade headquarters a

shelter-mounted AN/GRC-46 was provided to interface with

them.

Hot on the heels of the 173rd other

units began to arrive in Vietnam. Among the other units that

arrived during this period was a brigade of the 101st

Airborne Division, a brigade of the 1st Infantry Division,

and another from the 25th Infantry Division. These units too

saw their commo systems upgraded—and none too soon, as major

combat operations began almost the instant the troops from

these units hit the ground. In fact, by late 1966 six major

combat operations involving the soldiers of these brigades

were either underway or had already occurred, with five of

the six happening in the II Corps central threat area.[3]

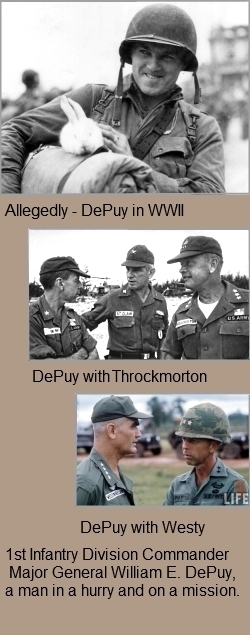

For

one of these campaigns the 1st Infantry Division (commanded

by Major General William E. DePuy) fielded an operation

called EL PASO II. It began on 2 June 1966, and depended for

its success on the solution to some weighty communication

problems… of both a logistical and operational nature.

From the get-go the 121st Signal Battalion had problems

deploying what was needed to support EL PASO II, as both the

men and the equipment it normally would have used were tied

up supporting the base camp complex at

Dĩ An.

Both men and material were dedicated to this large base

camp, and so it was necessary to find a way to extract the

121st from this duty so that it could focus its signal

duties on providing combat support for the 1st Infantry

Division, which was its normal organic role.

This was accomplished by reassigning the 595th Signal

Support Company to Dĩ An, attaching them to the 69th Signal

Battalion, and giving them responsibility for most of the

121st’s duties. An expedient, looking back now, one can see

that this quick fix was the beginning step in the never

ending game of “unit swap” that saw so many Signal Corps

units assigned, reassigned, and reassigned again throughout

the Vietnam War, until the TOE at the end of the war looked

nothing like it did at the beginning. Whether a mark of

typical American ingenuity or poor planning to begin with,

the flexibility the Signal Corps demonstrated as it moved

its units around the world to support operations in Vietnam,

as though they were pieces on a chess board, was a stroke of

genius. Come hell or high water, people and equipment were

going from where they were to where they were needed, the

TOE be damned.

This was accomplished by reassigning the 595th Signal

Support Company to Dĩ An, attaching them to the 69th Signal

Battalion, and giving them responsibility for most of the

121st’s duties. An expedient, looking back now, one can see

that this quick fix was the beginning step in the never

ending game of “unit swap” that saw so many Signal Corps

units assigned, reassigned, and reassigned again throughout

the Vietnam War, until the TOE at the end of the war looked

nothing like it did at the beginning. Whether a mark of

typical American ingenuity or poor planning to begin with,

the flexibility the Signal Corps demonstrated as it moved

its units around the world to support operations in Vietnam,

as though they were pieces on a chess board, was a stroke of

genius. Come hell or high water, people and equipment were

going from where they were to where they were needed, the

TOE be damned.

While the 595th helped free the equipment required for EL

PASO II, it didn't solve the problem of getting the

equipment to where it was needed, and making sure it could

be moved in real time as the troops moved. To solve this

problem the 121st copied what they had seen done by the 25th

Infantry Division. They modified the vans that carried the

VHF multi-channel AN/MRC-69 equipment by removing one stack

of AN/TRC-24 radio equipment and one stack of AN/TCC-7

carrier equipment (one-half the capability of the

AN/MRC-69).

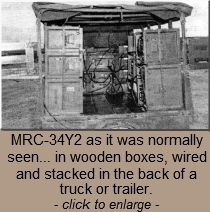

These

were then remounted in a 3/4-ton truck, or more usually

simply boxed in wooden crates that could be stacked together

on arrival at whatever forward base they were headed for,

wired back together, switched on and quickly operated while

the rest of the Signal squad built sand bag barriers around

this unattractive but all important pile of boxes. To make

the whole kludge look and sound like an authorized piece of

real Army equipment, the entire modified ensemble of commo

gear was given the name MRC-34Y2 and deployed. It proved

extremely successful in establishing VHF links in the field,

typically from a forward fire base back to a base camp. Best

of all, because the entire system weighed much less than the

AN/MRC-69 it was replacing, each individual wooden boxed

component could be hand carried by two men, slid inside the

belly of a UH-1, and transported along with the combat teams

as they moved from one forward base to another.

These

were then remounted in a 3/4-ton truck, or more usually

simply boxed in wooden crates that could be stacked together

on arrival at whatever forward base they were headed for,

wired back together, switched on and quickly operated while

the rest of the Signal squad built sand bag barriers around

this unattractive but all important pile of boxes. To make

the whole kludge look and sound like an authorized piece of

real Army equipment, the entire modified ensemble of commo

gear was given the name MRC-34Y2 and deployed. It proved

extremely successful in establishing VHF links in the field,

typically from a forward fire base back to a base camp. Best

of all, because the entire system weighed much less than the

AN/MRC-69 it was replacing, each individual wooden boxed

component could be hand carried by two men, slid inside the

belly of a UH-1, and transported along with the combat teams

as they moved from one forward base to another.

In the case of EL PASO II this proved invaluable as the

division and brigade command elements involved were spread

all over the tactical combat area, with ten distinct command

post locations operating at the same time. Many, being

expedient helicopter supported forward bases, were

inaccessible by any other means. Without the MRC-34Y2 being

Huey UH-1 helicopter-transportable, EL PASO II and the other

four combat operations that got underway in the summer of

1966 would have been in big trouble. Sure, bigger lifting

helicopters were available, but not in sufficient numbers to

support fluid combat operations where a forward operating

base might be changed every day of the week, and sometimes

twice on Sundays. Being able to rely on UH-1s made the job

of getting communication in place as the troops themselves

deployed doable. When the troops moved, their commo gear

followed them, in the same choppers that they rode in.

But that wasn’t the end of the problem. Unbeknownst to

everyone a new form of combat was in the process of being

invented, and this new form required that the Signal guys

that supported field operations had to invent new signal

solutions to cope with it.

Major

General DePuy turned out to be an aggressive combat leader.

Unlike General McClellan of Civil War fame, who couldn’t get

out of the way of his own shadow, or more precisely,

preferred not to, DePuy had no intention of letting grass

grow under his feet, or rice as the case may have been. His

plan was simple: move fast, hit hard. As a result he

initiated 1st Infantry Division tactics that rapidly

expanded the pace and scope of combat operations, more

quickly and intensely than any prior Vietnam Army commander

had. His troops moved as fast as the famous Generals Sherman

(again, of Civil War fame) and Patton (WWII), and possibly

faster, even without taking into account the fact that DePuy

rode on choppers while the best they had were horses and a

tank.

With DePuy it was not unusual to see a command post and a

few fire support bases appear one day, only to be moved the

next. DePuy’s approach correlated his troops physical

presence to the potential for action, putting his men in the

line of fire whenever he could, rather than waiting for the

line of fire to come to him. It may be an old infantry adage

that if you hear the sound of gunfire, head toward it, but

if it is, DePuy lived these words. He wanted to engage the

enemy and he expected his troops to move to do so whenever

the opportunity arose, even if that meant fighting while on

the move.

With this kind of an attitude what could the Signal boys do

but find new ways to not only keep up with him but prove

their mettle too by outpacing the ground pounders. This

caused them to have to come up with even more rapid

ways to deploy the communication assets at their disposal

and get them up and running quicker. In this case though the

problem wasn’t lack of equipment, it was the pace of

tactical combat change. In particular, the unique Vietnam

environment simply made communication at this pace anything

but reliable. The standard process deployment approach that

had been developed simply did not work. To fix the problem

the Signal boys turned to innovation again.

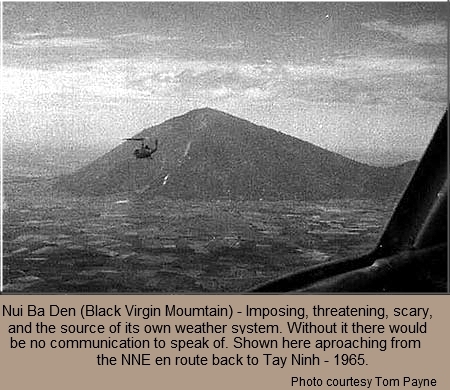

An

example of this can be seen at Nui Ba Den, one of the few

mountains of useful height in the 1st ID’s tactical area of

operation. It proved critical to maintaining a number of the

long multi-channel “shots” to the rapidly shifting forward

command post locations that filled the surrounding flat

land. But it wasn’t enough. After all, it was only one

mountain, where 20 were needed.

An

example of this can be seen at Nui Ba Den, one of the few

mountains of useful height in the 1st ID’s tactical area of

operation. It proved critical to maintaining a number of the

long multi-channel “shots” to the rapidly shifting forward

command post locations that filled the surrounding flat

land. But it wasn’t enough. After all, it was only one

mountain, where 20 were needed.

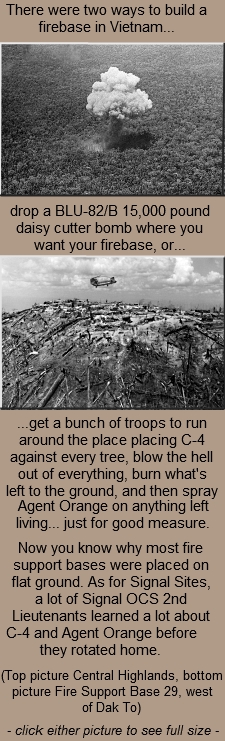

The answer of course was to erect signal towers. The only

problem was that back then the TOE for a Signal Battalion

didn’t include equipment for signal towers. Strangely, while

no such equipment existed or was authorized, signal towers

soon began to appear. Since few people knew that they

weren’t authorized or part of a Signal Battalion’s equipment

list, few people asked questions. For the most part

Captains, Majors, Colonels and the higher ranks that saw

them simply assumed that they were supposed to be where they

were, or they wouldn’t be there. No one asked how they got

there, who authorized them, or anything. And from the rank

of Lieutenant on down, no one told. When a tower was needed,

it just magically appeared. Another example of American

ingenuity at its best.

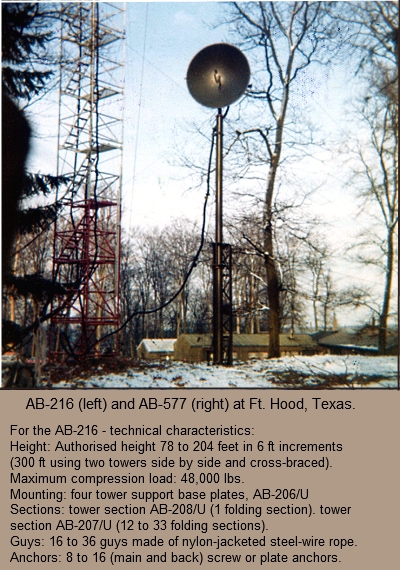

As to what they looked like, they were usually cobbled

together from the two standard issue systems that made up

the 45 foot AB-577 and the 65-foot AB-216. With a little

judicious use of guy wires these things could be erected up

to and over two hundred feet into the air.

How did the troops involved know this? Part of the answer

can be traced back to Army Signal OCS, at Fort Gordon, where

early 1966 Officer Candidates were shown how to erect

towers, guy them, and keep them up in the wind. Because of

this fortuitous training, when these same butter bars hit

the field in Vietnam and their EMs told them that the way to

solve the connection problem was to get the antennas up

higher than the surrounding terrain, they instantly thought

of the towers they had trained on back at OCS. The fact that

this solution involved equipment that was not authorized to

their units, or readily available, didn’t matter. What

mattered was getting the message through… and they knew that

could be done by simply putting an (unauthorized) tower

higher than anyone had before. Wet behind the ears as Second

Lieutenants they may have been, but intimidated they were

not. After all, they had themselves built these same towers

back on the fields of Signal OCS and so knew that the

equipment was strong, reliable, and not beyond their ability

to master.

And so it happened, Enlisted ingenuity and the excitement of

Junior Officer command led to signal towers popping up all

over the place in the II Corps zone, authorized or not. Find

a field command post or forward fire base in Central Vietnam

and the chances are you would also find a couple hundred

feet of tower sticking up into the sky.

And so it happened, Enlisted ingenuity and the excitement of

Junior Officer command led to signal towers popping up all

over the place in the II Corps zone, authorized or not. Find

a field command post or forward fire base in Central Vietnam

and the chances are you would also find a couple hundred

feet of tower sticking up into the sky.

Whatever the cause, whatever the reason, it worked. These

off-the-cuff towers kept the VHF and UHF systems on air,

providing to every major combat unit the voice of command

they needed.[4]

As to what all of this accomplished, it set the tempo and

tenor for how tactical Signaleers would face the war ahead.

By combining rapidly constructed towers of the kind first

learned about back on the training fields of Signal OCS with

ground and light air-transportable equipment layouts, wooden

boxed pieces of signal equipment kluged from much larger

systems, air borne relay stations, and upgraded VHF and UHF

equipment, field signal platoons were able to install,

operate and maintain backbone field expedient multi-channel

trunking and switching systems able to meet the needs of any

tactical combat field unit… of any size… any complexity… at

any number of forward bases… in support of any combat team

with a fire in their belly to find and fix the enemy, and

jump to the occasion by moving itself at the trigger of a

trip wire from where it was to some other God forsaken

location in Vietnam… and then get up and do it all over

again the next morning.

Yet while all in all the system worked and worked well, it

wasn’t perfect. As the combat units settled into their

routines the pace quickened even more, bringing the rate of

combat engagement up several notches higher than that which

had been set when they first arrived in country.

The case of the 1st ID gives an example. For it the links

the commo guys set up between the main command post at Dĩ An

and the brigade main command post at Phuoc Vinh worked well,

but still only provided basic communication. So too for

communication between the brigade command post and the

division's forward command post at Lai Khe, and similarly

for division support command, which was tied into brigade

headquarters at Dĩ An. All in all, basic communication… with

a jump capability thrown in to tie together the division and

brigade tactical command posts whenever they were deployed.

But beyond that, the system simply could not keep up with

the evolving needs of the combateers, especially as their

commanders grew to spend more and more time in the air. In a

nut shell, the combat commander’s growing penchant to spend

as much time in the air as they could, applying and employing

helicopter borne command and control rather than pacing back

and forth in an office back in the rear, put a stress on

field communications that the Signal Corps had not seen in

all the wars before.[5]

How did the Signal Corps fix this problem? You’ll have to

read Part II to find out that answer. In Part II

we’ll take a look at the communication problem helicopter

borne command and control created, and how the Signal Corps

went about solving it. Join us there to continue the story of

the Signal Corps’ efforts in the 1965 – 1967 period, when

the war began in earnest.

Footnotes

[1]

Sources and cross check for comments about non-notification

of government of South Vietnam:

— Neil Sheehan, Hendrick Smith, E.W. Kenworthy, and Fox Butterfield, eds.,

The Pentagon Papers (New York: Bantam Books, 1971)

— William Bundy’s

unpublished manuscript, chapter 19, as read and commented on

by Bui Diem, member of the delegation to the 1954 Geneva conference,

Chief of Staff to the Premier of South Vietnam, 1965, et al.

— U. Alexia Johnson,

The Right Hand of Power (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.:

Prentice-Hall, 1984)

- To return to your place in

the text click here:

[2] For a well written, brief history of the 173rd in

Vietnam, see this Wikipedia article:

- To return to your place in the text

click here:

[3] EL PASO II, HAWTHORNE, PAUL

REVERE, SILVER BAYONET, MASHER/WHITE WING [Click here

for

map of combat operations]

- To return to your place in

the text click here:

[4] At Dĩ An base camp the tower stood at 120 feet. At

Christmas the Signaleers traded around until they had enough Christmas

lights to wrap the guy wires. To make sure the symbolism wasn’t missed, they

topped it with a huge star. One written archive of the time stated that when

“the Big Red One communicators gathered about the tower, the commanding

general of the division commended them for their outstanding work as

communicators and, at the conclusion of his remarks, officially lit the

‘tree’.” Little did he know that the tower was not part of the TOE, was

unauthorized and built from scrounged parts and materials. As the ceremony

proceeded, starting with a few 1st Lieutenants and on down through the

enlisted ranks, smiles and chuckles spread throughout the assembly as the

idea gained momentum that they were being commended for what was essentially

an unauthorized activity and something that flaunted SOP. For most of the

higher Officer ranks however, at least for those that noticed the levity and

jostling of the crowd, the question was bantered about as to what the troops

found so humorous that they could hardly contain themselves.

- To return to your place in the text click here:

[5] Dĩ An is a town in Binh Duong province in

southeastern Vietnam, about 20 km north of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). It

is 1706 km by rail from Hanoi. As of the 2009 census the town had a

population of 73,859. The town covers 60 km².

- To return to your place in the text click here:

Additional Sources

Primary source material, data and statistics used in this

article taken from Vietnam Studies, Division Level Communication, 1962 -

1973, Lieutenant General Charles R. Myer.

Like this

synopsis of history? Let us know by

helping us with our scholarship fund efforts. A $30.00 donation

to our

Scholarship Fund

will help us get one step closer to helping another deserving High School

graduate attend college. Your donation is tax deductible and your

kindness will go father than you think in making

it possible for another young American to fulfill their dream of a college

education. Thank You!

This story originally published on our February 2013 Home Page.