Continued from the August 2012 Home Page. To go to an archived version of

that page click here:

August

2012 Home Page Archive. To return to this

month's actual Home Page click on the Signal Corps

orange Home Page menu item in

the upper left corner of this page.

continuing...

For

America’s Army, the ones who will be tasked with building

relations with the Burmese Army, this will present a

problem. Whether we accept it or not if America wants close

ties with Burma our Army is going to have to engage with the

Burmese Army just as strongly and closely as our State

Department does with Burma’s diplomats. And if that happens

the U.S. Army will be dragged into this internecine

conflict.

For

America’s Army, the ones who will be tasked with building

relations with the Burmese Army, this will present a

problem. Whether we accept it or not if America wants close

ties with Burma our Army is going to have to engage with the

Burmese Army just as strongly and closely as our State

Department does with Burma’s diplomats. And if that happens

the U.S. Army will be dragged into this internecine

conflict.

The question is, what will the U.S. Army do when their new Burmese

friends come to them for advice on how to handle the ethnic

tension that permeates the country? Perhaps more to the

point, what will they do if their Burmese Officer friends do

not come to them for advice and simply light out for the

countryside with a few regiments to slap the Atsi, Bwe or

Chin minorities back into place?

If the U.S. Army is not careful it could find itself not

only allied with but possibly responsible for the Burmese

Army reverting to its old ways.

On the good side, for the time being the military is taking

advice from the newly formed central government, with the

government actively trying to use diplomacy instead of

military force to keep the natives calm. This has brought a

few breakthroughs, as in January the government signed a

ceasefire with the rebel Kachin (a.k.a. Kayin and Karen)

ethnic group, one of the more aggressive and well armed of

the minorities.

On the bad side, in June communal violence broke out between

the Rakhine Buddhists and the Muslim Rohingya. More than

just being a religious matter, the Rohingya people not only

don’t like the Rakhine but also hate both the central

government and the military. The reason? Back in 1982 the

military leaders at that time collectively revoked the

Rohingya’s citizenship. Talk about a reason to want to be

separate from the nation the world tells you that you are a

part of.

One might ask the question then, if today was five years

into the future and the U.S. Army had already built solid

ties with the Burmese Army… such as hosting Burmese Officers

at U.S. facilities for exercises, education, training and

the like… what advice and help would we give to them in

trying to help them bring the Rohingya back into the fold?

Our answer would be one word: COIN. More to the point, we

would hope that by five years down the road from today the

U.S. Army would have already graduated a number of

COIN

qualified Burmese Officer leaders who would by then have

been well along the road towards implementing this “weapon

system” with the dissatisfied tribes, long before any of

them took to the jungles to mount an insurgency campaign.

This

then is what we meant when we began this article by speaking

of the need for U.S. Army Officers to understand the lay of

the land of the nations of Asia that the ‘rebalance

strategy’ is impelling us to engage with. Unless we know who

they are, what they are, and what problems they are

facing—and plan for ways to help our new friends resolve

those problems—we won’t be able to effectively bring these people into

our embrace… neither our military embrace, diplomatic

embrace, nor the embrace of our national values.

This

then is what we meant when we began this article by speaking

of the need for U.S. Army Officers to understand the lay of

the land of the nations of Asia that the ‘rebalance

strategy’ is impelling us to engage with. Unless we know who

they are, what they are, and what problems they are

facing—and plan for ways to help our new friends resolve

those problems—we won’t be able to effectively bring these people into

our embrace… neither our military embrace, diplomatic

embrace, nor the embrace of our national values.

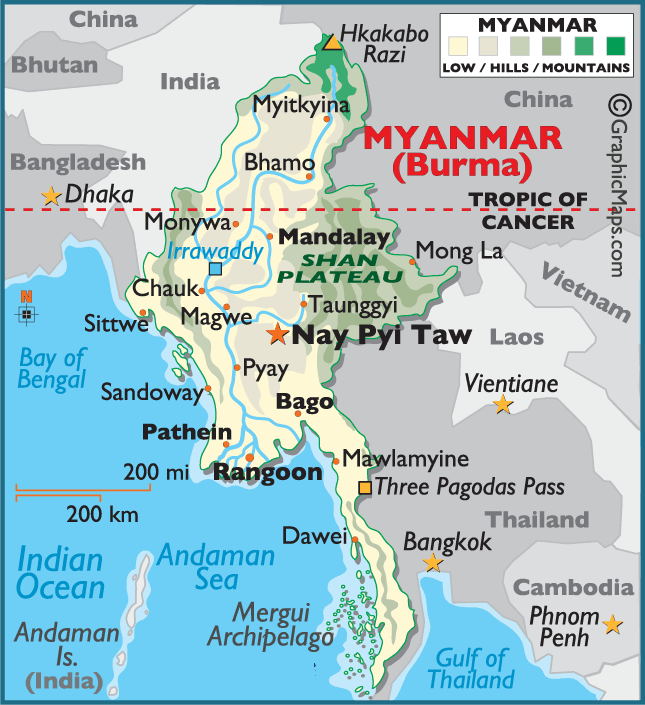

Ethnic tension aside, as it comes together to build

relations with the Burmese Army the U.S. Army’s role in

Burma won’t end there. We are not the only country to notice

that Burma is making moves suggesting it wants to be part of

the world again. In May Manmohan Singh, the Prime Minister

of India, paid the country’s first official visit to Burma

since 1987. While there he just happened to sign 12

agreements to strengthen trade and diplomatic ties,

including a couple that specifically provided for border

area development supported by an Indian line of credit.

So the question is, how good are our relations with India?

Is India’s sudden interest in Burma a problem for us or a

benefit? Students of India will remember that India has that

strange appendage that the British left them with, above and

to the right of Bangladesh. An appendage that is a part of

their country but seems not to be part of it at all. Looking

at it reminds one of that saying that Maine farmers utter

with their Downeast accent when you stop and ask them for

directions: welp… you caint get theah from heah.

Fortunately

for India, but perhaps not so fortunate for us, with new

relations with Burma India will finally be able to get there

more easily via Burma than via its own back yard, thus

avoiding the need to keep things on an even keel with either

Bangladesh or China. And considering that India and China

still on occasion raise their voices over their common

border, having an India that can flex its muscles when it

wants to might not prove well for America, especially if we

are both shoving our elbows in an attempt to be the first

country to work its way through Burma up to the border with

China.

Fortunately

for India, but perhaps not so fortunate for us, with new

relations with Burma India will finally be able to get there

more easily via Burma than via its own back yard, thus

avoiding the need to keep things on an even keel with either

Bangladesh or China. And considering that India and China

still on occasion raise their voices over their common

border, having an India that can flex its muscles when it

wants to might not prove well for America, especially if we

are both shoving our elbows in an attempt to be the first

country to work its way through Burma up to the border with

China.

Also, from India’s perspective, having the U.S. on its

eastern border as well as its western (via Afghanistan) may

not sit well with India’s military. For example, in addition

to the U.S. gaining a land presence on India’s eastern flank

via a new relationship with Burma, it will now have a chance

to extend its presence into what were previously considered

(by India) as its home waters. Specifically, without a

foothold in either Bangladesh or Burma the U.S. has been

unable to make its presence known in the Bay of Bengal.

Unlike the Arabian Sea, which the U.S. military has treated

as an active zone of presence for many years, the Bay of

Bengal has been something that India has considered as its

own backyard. If America moves into Burma and gains a

military presence there, this is bound to result in the U.S.

Navy extending its presence to the Bay of Bengal. Without

doubt this will not sit well with India.

One can see than that while there have been no points of

confrontation between the U.S. and India to date, that

doesn’t mean there won’t be any in the future. Remember, in

the past the U.S. and India rarely ran across each other.

Now we will both be vying to become Burma’s BFF. That is

bound to bring some tension.

Then there is China itself. As evidenced by the quick trip

that Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping took to Burma in

November of 2011, where he offered to boost military ties

with the country days ahead of U.S. Secretary of State

Hillary Clinton's historic visit to Burma, the U.S.' efforts

to begin building ties between our military and Burma's

seems to make Beijing very, very jittery. And while in

public China's leaders may say otherwise and act like it

could care less if America engages with the newly opened

Burma, deep down inside it is petrified of having the U.S.

box it in via one more country. And this one right on its

southern doorstep.

From America’s perspective engaging with Burma is critical

to our national defense. If there is one lesson that we

should have learned by now it is that our past decade of

“strategic neglect” as regards the rise of China’s military

has left us almost wholly unable to counter their new

assertiveness. The net result is that since we failed to

deal with China when we could have, now we are forced to

fall back on the threadbare concept of a “strategy of

containment.” In our view a strategy of containment is no

strategy at all. It’s simply a phrase that makes us feel

better when there is nothing else we can do to change the

outcome of an imbalance between our country and another,

something we allowed to happen on our watch. Containment is

little better than closing our eyes and hoping the problem

goes away.

So

how did we get here? For nearly two decades America's

leaders talked up the idea of engagement with China but

never backed up our talk with muscle when China gained the

upper hand via cunning, deceit and chicanery … not with

trade, not with monetary policy, not with tariffs, not with

exchange rates, not with price fixing, not with pirated

intellectual property, not with North Korea, not with

China’s stalling moves in the UN, and certainly not when our

militaries bumped heads (think: the 2001 Hainan Island

incident). So, since we don't seem to have the diplomatic

courage to stand up to them, absent our ability to occupy

another square on the chess board, what makes us think that

we will be able to contain China now?

So

how did we get here? For nearly two decades America's

leaders talked up the idea of engagement with China but

never backed up our talk with muscle when China gained the

upper hand via cunning, deceit and chicanery … not with

trade, not with monetary policy, not with tariffs, not with

exchange rates, not with price fixing, not with pirated

intellectual property, not with North Korea, not with

China’s stalling moves in the UN, and certainly not when our

militaries bumped heads (think: the 2001 Hainan Island

incident). So, since we don't seem to have the diplomatic

courage to stand up to them, absent our ability to occupy

another square on the chess board, what makes us think that

we will be able to contain China now?

The only thing that will work, and this is perhaps our last

chance, will be to build a strong and long term relationship

between the U.S. military and the Burmese military. To

occupy the square on the chess board that is marked Myanmar.

That will contain China.

As to why our China containment strategies of the past have

failed, it’s because we failed to recognize that the

security architecture we need to keep China in check

requires that we have a position on the eastern flank

of the Asia Pacific. For nigh on 45 years now, since

Vietnam, we have done nothing about staking one out, with

the result that China has grown in influence throughout the

region. And now that it has the economic muscle to stand

behind its expansionist goals, without such an eastern flank

focused architecture there is little America can do to stop

it. From this perspective, gaining a land and political base

with a friendly eastern flank country is a strategic

imperative.

For those who failed in geography China’s eastern flank

really means the eastern flank of Asia, not the eastern

flank of China. This area includes Vietnam, Laos, Burma,

India, and to a lesser extent Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal.

In this regard, it is true that it could be said that the

United States has a Strategic Partnership with India of

sorts, but there is no such linkage with Burma or

Bangladesh. And even in India’s case, the Strategic

Partnership is more of a diplomatic nature and less one of

trade or military ties. After all, you don't exactly see

India coming to our aid in Afghanistan... or putting a

little pressure on Pakistan to clean up its terrorist

infested house, do you?

Looking at this eastern flank, of all of the available

countries we could partner with to "contain" China, Vietnam

would probably be a better bet than Burma. But hey, we

already tried that, and it’s highly unlikely Vietnam is

going to let us set up a military base in North Vietnam

anytime soon. That leaves Burma, a country that has

overwhelming military significance for the US’ rebalancing

strategy, not to mention military significance via Burma's

geographic contiguity with China in its northern and

north-eastern provinces. The problem though is that over the

past 60 years China has made sizeable strategic,

military and political investments in Burma… surprise… as

part of its counter-containment strategy aimed at the United

States.

Where

does that leave us in the U.S. Army? Considering that even

with the political changes afoot in Burma the Burmese

military will run the country for decades to come (think:

Turkey), the only way to broaden ties between the U.S. and

Burma will be via military to military contacts… in other

words by having the U.S. Army take the lead in building

closer ties with the Burmese Army.

Where

does that leave us in the U.S. Army? Considering that even

with the political changes afoot in Burma the Burmese

military will run the country for decades to come (think:

Turkey), the only way to broaden ties between the U.S. and

Burma will be via military to military contacts… in other

words by having the U.S. Army take the lead in building

closer ties with the Burmese Army.

Why? Because military people are alike no matter what

uniform they wear: we think the same, we talk the same

language, and we view the world through the same

conservative but jaundiced glasses. Because of this the U.S.

Army will be able to do things to influence Burma’s behind

the scenes military rulers that the State Department

attachés would never be able to do. Like get them to toss

their friend China out of the barracks in favor of the new

guy on the scene: America.

Strategically, it is an American imperative that the U.S.

loosen the linkage between Burma and China. In our view only

the U.S. Army can do that.

As important, much of that strategic imperative comes from

military needs, and who better to deal with strategic

imperatives born out of military matters than the military

people who will have to fight to overturn those matters if

the cause that created them is not peacefully undone. A few

examples will suffice.

For

one, unless the U.S. military is able to gain a peaceful,

respectful, mutually beneficial foothold in Burma—alongside

of and sharing beers at night with our new friends in the

Burmese Army—it may one day find itself facing China’s

military sunning itself on the Indian Ocean. The reason is

that China’s current strategically cooperative relationship

with Burma gives it land access to the Bay of Bengal and the

Indian Ocean. So, since the U.S. military will be the ones

called to block China’s advance via this route during a time

of conflict, who better to figure out how to undo this

“opportunity” for China now than the U.S. military? Since we

are being sent over to Burma today to begin building better

relations between our two militaries, shouldn’t we get busy

figuring out how to get the Burmese to peacefully deny this

route to China rather than wait until we have to stop the

Chinese Army with the 1st ID?

For

one, unless the U.S. military is able to gain a peaceful,

respectful, mutually beneficial foothold in Burma—alongside

of and sharing beers at night with our new friends in the

Burmese Army—it may one day find itself facing China’s

military sunning itself on the Indian Ocean. The reason is

that China’s current strategically cooperative relationship

with Burma gives it land access to the Bay of Bengal and the

Indian Ocean. So, since the U.S. military will be the ones

called to block China’s advance via this route during a time

of conflict, who better to figure out how to undo this

“opportunity” for China now than the U.S. military? Since we

are being sent over to Burma today to begin building better

relations between our two militaries, shouldn’t we get busy

figuring out how to get the Burmese to peacefully deny this

route to China rather than wait until we have to stop the

Chinese Army with the 1st ID?

For another, one of China’s main goals in getting closer to

the Burmese military rulers is to enable construction of a

well thought out overland oil pipelines grid that will take

oil from the Burmese coast to South China. More than a means

to bring more oil to China’s sweatshops, this is a coveted

goal of the Chinese military, designed to outflank and avoid

dependence on the Straits of Malacca for oil supplies. Why?

Because the U.S. Navy can easily block the Straits and deny

critical oil to China’s military in a time of conflict.

Again, if the case has to be made between using U.S.

diplomats to persuade Burma’s military leaders to put a stop

to this project, or U.S. military personnel who are resident

in the country as part of a long term exchange program, then

this author would vote for the military. Why? Because

military people speak the same language, and it is easier

for a Burmese General to ask a U.S. Army General for new

toys to play with if he is to grant the U.S. General’s wish,

than a State Department official that a) does not know what

the new toy’s kinetic strength is, b) will have to go to the

Pentagon to get it approved anyway, and c) will (because of

his liberal mindset) fear giving any kind of new weapon

system to the Burmese military.

Summarizing then, it is easy to see that most of the reasons

for needing a containment strategy for China stem from

military matters to begin with. Considering that Burma is

ruled by military leaders, it is only natural that the U.S.

military, with the Army in particular, should carry a better

than fair share of this load. Whether it’s the need to deny

China a land bridge to the Bay of Bengal, stopping an oil

pipeline that benefits few more than China’s army, or

securing military oversight over the offshore oil-blocks

sprinkled throughout this region (think: the ‘energy

strangulation’ of China), all of these factors and more come

into the picture only because of strategic military

necessities. Who better then to manage America's resolution

of these strategic military necessities than America's

military? And, since management will entail working closely

and on a day to day basis with Burma's Army, who better

within the U.S. military than the U.S. Army?

Finally, if reading this causes you to pay attention to

future news items about how China views the U.S.’ intentions

in Burma, pay no attention to the claims China makes that

the U.S. and China have no reason to clash over Burma. The

truth is otherwise. China has invested substantially in this

country over the last three decades and they are not

prepared to lose. They would rather go to war than see the

U.S. Army have a base in Burma.

Have a comment on this article? Send it

to us. If you are a member of the Association we will

gladly publish it.

If you are not, well, it only costs

$30.00 a year to become a member and have your views heard...

and because

we are a fully compliant non-profit organization your payment is tax

deductable.