- This is Part III in a Three Part Series -

This article originally published on our Home Page in February 2012

[Please Note: Any opinions

expressed in this article are those of the author

and do not necessarily represent the U.S. Army

Signal Corps OCS Association]

This article is the third in a series

regarding the Signal Corps and its path of evolution

from WWII through Korea to Vietnam. The first two,

The Signal Corps During

World War II, and

The Signal Corps During The Korean

War, can be found on our

Brief Histories page.

There is a quick link to them

at the bottom of this page.

In each article we have tried

to take a 50,000 foot view of what the Signal Corps

did during these wars, and determine from such

observation how it affected the Corps’ evolution

from the simple mission it had when it first came to

prominence during the Civil War, to the complex

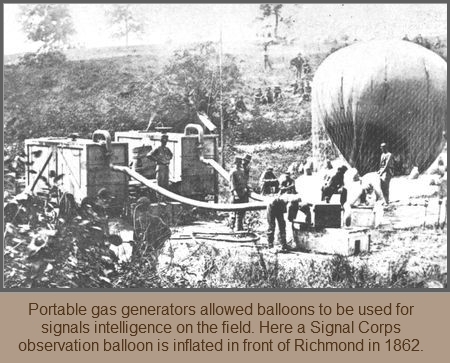

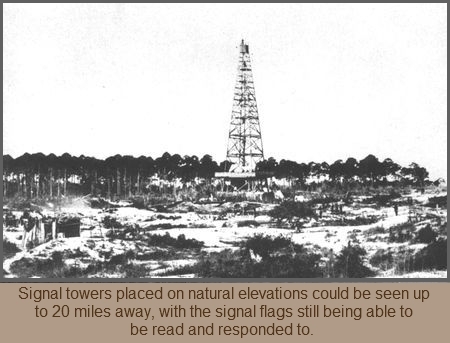

mission structure it holds today. If one looks back

on those early days and considers that at the time

of the Civil War the Signal Corps’ primary task was

simply to observe the enemy (usually from a hot air

balloon), report on its activities, and deliver

messages via pigeons or signal flags, one can see

that today its mission to do everything from manage

strategic DOA and DOD assets to being responsible for…

In each article we have tried

to take a 50,000 foot view of what the Signal Corps

did during these wars, and determine from such

observation how it affected the Corps’ evolution

from the simple mission it had when it first came to

prominence during the Civil War, to the complex

mission structure it holds today. If one looks back

on those early days and considers that at the time

of the Civil War the Signal Corps’ primary task was

simply to observe the enemy (usually from a hot air

balloon), report on its activities, and deliver

messages via pigeons or signal flags, one can see

that today its mission to do everything from manage

strategic DOA and DOD assets to being responsible for…

• Automation, communication, electronics and

network planning, design, engineering,

evaluation, management, installation, operation,

logistical support, and maintenance of signal

equipment and systems; to

• Advising

commanders, directors, and staff on command and

control signal requirements, capabilities, and

operations, including computer systems, data

management, signals intelligence, signals

monitoring, and network operation; to

• Developing requirements for the design and

implementation of local, regional and global

data, mobile, and fixed communications systems

and networks; as well as

• Establishing, preparing, coordinating and

directing programs, projects and activities

engaged in unit level supply, logistics,

maintenance, and life-cycle management of

worldwide signal materiel; to

• Integrating tactical, strategic and

sustaining base communication, information

processing, and management systems into a

seamless global information network able to

support knowledge dominance for the Army as well

as joint and coalition operations; to

•

Directing and controlling of the units and

activities involved with the application of

electrical, electronics, and systems engineering

and management principles in the design, test

acceptance, installation, operation, and

maintenance of signal systems, equipment,

databases, networks, and facilities; to more

esoteric activities such as

•

Directing and controlling of the units and

activities involved with the application of

electrical, electronics, and systems engineering

and management principles in the design, test

acceptance, installation, operation, and

maintenance of signal systems, equipment,

databases, networks, and facilities; to more

esoteric activities such as

• Operating photo and video service

undertakings that run the gamut from documenting

combat activities to archiving the same,

performing radio, data and other signal

intelligence functions, to

• Developing and implementing radio and

radar countermeasures, establishing airway

communications systems; and of course

• Participating in all manner of combat

activities from support of joint-assault signal

operations through to the most simple but

critical defense of individual signal sites…

we can see that much has changed

in the Signal Corps.

The question we have been trying

to answer through these three articles has been how

did these changes come about and why. The answer we

found is that the real time pressures of war,

followed (in most cases) by government mismanagement

of military budgets between wars, caused these

changes.

In

great part, the bulk of the changes in the Signal

Corps’s approach to its duties came about during

WWII, Korea and Vietnam... and the times between

them. It’s because of this that our focus over the

past two articles has been on the Signal Corps

during the first two of these wars. In this article

we finish our series by looking at how the Vietnam

War forced further change upon the Signal Corps.

Looking back over the prior two pieces, we can see

that one of the key lessons we learned in looking at

the Signal Corps during WWII and Korea is that

unlike most branches of service where the task is

singular, comprising little more than one of giving

combat in a manner that contributes to winning a

war, the Signal Corps has evolved during these

periods to fulfill two

roles. In military speak, it could be said that

while other branches of service focus narrowly and

almost exclusively on their task at the operational

level of war, the Signal Corps found that in order

to meet its ever evolving mission, it needed to

expand its operational concept to take in not only

the application of military art and science to areas

within the operational level of war, but also

external to it.

Looking back over the prior two pieces, we can see

that one of the key lessons we learned in looking at

the Signal Corps during WWII and Korea is that

unlike most branches of service where the task is

singular, comprising little more than one of giving

combat in a manner that contributes to winning a

war, the Signal Corps has evolved during these

periods to fulfill two

roles. In military speak, it could be said that

while other branches of service focus narrowly and

almost exclusively on their task at the operational

level of war, the Signal Corps found that in order

to meet its ever evolving mission, it needed to

expand its operational concept to take in not only

the application of military art and science to areas

within the operational level of war, but also

external to it.

In this

regard, the first role the Signal Corps carries out

obviously relates to being a partner war fighter,

along with all of the other branches of the U.S.

military. Considering that over the past 60 years

the Signal Corps has been first a part of the combat

arms, then not, and then later included again, being

a partner war fighter has not always been easy.

Whether formally a partner war fighter or not, in

this role the Signal Corps, like its sister

branches, puts its men on the line—engaging the

enemy where and when needed, as it goes about its

task of providing any and all support required to

deliver the communication capabilities essential to

the other branches sharing the combat field with it.

The second, as the reader can

intuit from the list above, relates to providing the

kind, type, and quantity of communication and signal

capabilities necessitated by the nature and

characteristics of the war, situation, or conflict

underway. And while the glory in what the Signal

Corps does may rest within the former role of a war

fighter, it is the work done within this latter

category that earns the Signal Corps its stripes.

Two simultaneous missions: that of a war

fighter, and that of the provider of any and all manner of

communication—or as we know it today, Information Technology

(IT), Information and Communication Technology (ICT),

Information Systems (IS), Information Management (IM),

Knowledge Management (KM), Technical Science Management and

Application (TSMA), and Data Management (DM)—as may

be required by the nature and characteristics of the

conflict in question.

Without these two tasks being successfully

performed by the Signal Corps, combatants from the other

branches would find themselves existing and fighting within

a vacuum... a vacuum void of information about the enemy,

his position, intentions, status, and pattern of

methodological behavior.

For if the truth be told, these latter five elements form

the determinants of war in the modern age, and it is the

Signal Corps that is first and foremost responsible for

assisting in their identification, documentation, and

communication to the rest of the military.

One can see then that as both the foundation

and the glue that makes possible an effective response to

the numerous war activities the U.S. military gets involved

in, by enumerating to its sister branches an enemy’s

position, intention, status, and pattern of methodological

behavior, the Signal Corps is the enabler that allows the

sister services to act with both precision and objective

intent. In other words, because of the information

communicated by the Signal Corps, its

sister services, such as the Infantry, are able to use this

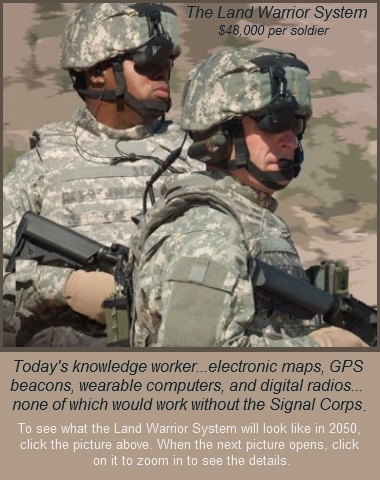

knowledge to their collective advantage. In today’s modern

world, it would be said that the Signal Corps enables the

Infantry to turn its troops into

knowledge workers.[1]

And yet while this seems self obvious to us today, the

reader should recognize that the calling to serve this

purpose is not only a far cry from the job the Signal Corps

originally set out to do when it was founded, it is as

equally far a cry from that which it did during the second

world war and Korea. The Signal Corps has evolved. As

pundits would say today, it’s not your father’s Signal Corps

anymore.

As we saw in the previous two articles, WWII

challenged the Signal Corps to develop several capabilities

that it did not previously have, while the Korean War helped

the Signal Corps to figure out how to better deliver these

capabilities. One of the more important of these

capabilities involved expanding the role of the Signal Corps

to support a method of war-fighting originally developed by

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, but not fully applied since then

until WWII. A basic tenet of how America fights wars even

today, Grant’s doctrine revolved around the emphasized,

overwhelming, and continued application of military force

directly

against the enemy army, as well as indirectly

against the enemy's civilian population (read: the

civilian-industrial sector), to prevent the civilian sector

from acquiring the resources (including the availability of

civilian manpower itself) needed to support the military.

With no insult meant, Colin Powell’s famous Powell Doctrine

of the application of overwhelming force in time of war is

simply a restatement of Grant’s original war strategy, and a

not very original one at that.[2]

In applying force against an enemy’s

Army, clearly, a key part of this is knowing where the enemy

is and what his intentions are. In depriving the military

and its supporting civilian population of their ability to

provide resources to the enemy, the important part is

identifying both what resources the military needs, as well

as who is providing them to the military.

In both of these instances, a quick

reflection will show that it is the Signal Corps that has,

time and again, stepped forward to help solve the riddle of

how to identify the who, what, where, when, and why embedded

in matters of war, and communicate this information to the

troops in the field. In the first instance, the Signal

Corps’ development of RADAR serves to make this point.

Whether it was the kind of RADAR that first detected Japanese

Zeros approaching Hawaii on December 7, 1941, or the kind of

X Band RADAR that was first used to locate mortars, the

objective was the same: identify the enemy’s intentions,

locate them, and distribute this information to those in the

field.

In the second case it was the Signal

Corps’ development of signals intelligence that led the way

towards identifying the tie in between military resources

and the civilian counterparts that provided them. Signals

Intelligence, combined with the Signal Corps’ development of

encrypted as well as burst radio communication, allowed U.S.

saboteurs to step in and deny these resources to the enemy’s

military.

World War II then served as a crucible in helping mold from

the tailings of the old-school military of World War I a

modern Signal Corps able to apply newer and rapidly evolving

forms of technology to the purpose at hand. What it failed

to do however was help the Signal Corps develop an

organizational structure able to anticipate and respond to

the sort of quickly changing battlefield conditions that

were looming (as WWII was brought to a close) just over the

horizon.

Korea did that.

As we saw in the last article, the

Korean War brought home to roost the necessity for the

Signal Corps to wrench itself from its stayed approach to

handling operational situations, instead creating a means to

transform itself on the fly… applying in each and every case

that it was presented with the kind of American leadership,

creativity, and problem solving skills that are required if

one is to succeed in a fluid situation. As the Signal Corps

learned then, key to doing this was being able to

distinguish where rapid transformational abilities were

needed and should be allowed, versus those situations where

transformational pressures should be resisted and things

forced to continue to be done “by the book.”

Remarkably, the Signal Corps succeeded

in this vetting conundrum. It succeeded by unknowingly

becoming the first military institution to define and apply

process management to its mission. A term that came into

vogue only in the early 1980s, the Signal Corps during the

Korean War was one of the first to define this approach to

task management, becoming its own internal proponent of the

use of what is today known by the terms TQM, Six Sigma, QMS,

process management, and a dozen others. With focus and

purpose but unmindful that it was charting new territory,

the Signal Corps wrote process management dictums into its

SOPs even as the Korean War unfolded.

As to why

this was necessary, battlefield conditions of the Korean War

presented the Signal Corps with the need to integrate

in real time

its ability to find, trap and analyze exocentric knowledge

of the enemy's intentions and activities... from all

available sources and services... in order to build ever

quicker, faster, cheaper, better endocentric means of

analyzing and sharing this information with the combat arms

most in need of it.

Process management, when used as

a means of solving real time war problems, is ideal for this

purpose as it helps strain out nonstandard data points in

the collection and analysis effort. For the Signal Corps

then, the Korean War proved to be another important period

of transition, in both how it selected, trained, organized,

and managed its personnel, as well as how it managed itself

in performing its core tasks of analyzing and communicating.

In all of this, developing multiple technological means to

address each communication need that appeared inadvertently

led to what was likely the first ever effective application

of process management techniques in a hot war environment.

By the end of the Korean War the Signal

Corps had found itself in a new place in military society.

By 1960 the Signal Corps was the Army's third largest

branch, comprising about seven percent of its strength. In

1961 the Army redesignated the Signal Corps as a combat

arm again, a privilege it lost at the end of the second world war,

while at the same time keeping its designation as a

technical service arm.

By the end of the Korean War the Signal

Corps had found itself in a new place in military society.

By 1960 the Signal Corps was the Army's third largest

branch, comprising about seven percent of its strength. In

1961 the Army redesignated the Signal Corps as a combat

arm again, a privilege it lost at the end of the second world war,

while at the same time keeping its designation as a

technical service arm.

Unfortunately, as with the end of WWII and every war that

preceded it, with the suspension of combat operations in

Korea America’s federal government set about the task of

looting the military one more time, in a mad rush to reorganize it,

ostensibly to “learn from the lessons of Korea.” Why the

U.S. government continues with this charade of cutting

military expenditures once a war has ended (under the

pretense of making the military more efficient or

effective), one can only imagine. Yet, like clockwork, as

soon as a war has ended, government leaders set about

wielding their ax to the military… as though the U.S. will

never again fight another war.

One can see it happening today. With President Obama

announcing in January 2012 his plans to reorganize the

post-Iraq, post-Afghanistan U.S. military, his efforts are

at best feckless and at worst one of the most irresponsible

things a president can do. Cutting the size of the military

under the guise of making it more suitable to large scale

naval engagements between nuclear powers,

during a time of increasing tension between the U.S. and any

number of countries, is in total contravention of the

very reason for a people to have a government in the first

place.[3]

In this Editor's view, Obama’s actions

today are no less imprudent and irresponsible than those of

the leaders who, after World War II, gutted America’s

military to the point that it was unable to fight in Korea

without mounting a draft and scavenging the whole of Japan

for every piece of armament that could be found.

Decorated with disingenuous statements about how his new

changes will make the U.S. Army better structured to fight

the future wars that Leon

Panetta says are coming, President Obama should

learn from what happened in Iraq when Rumsfeld’s lofty goal

of developing a new, more nimble, smaller footprint military

had to be shelved because… gosh, what a surprise… wars

require overwhelming force to win.[4]

This digressive rant aside, the military at the

conclusion of the Korean War, the Signal Corps included, was gutted one more

time, in another round of post-combat capability reductions… of a type that

had an impact on the upcoming war in

Vietnam. Fortunately, unlike when the

U.S. military’s global communication network ACAN (Army Command and

Administration Network) was rent asunder between the end of WWII and the

beginning of the Korean War, post-Korea the newly named and established

Defense Communications Agency decided to maintain the global communications

network then in place, and even expand this worldwide, long-haul system to

provide still greater, secure communications. Thus, for the first time in

the nation’s history the president, the secretary of defense, the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, government agencies, and the military services, not to

mention America’s diplomats abroad, had access to a fully integrated,

secure, global communication network at the time the Vietnam War got

underway.

Vietnam. Fortunately, unlike when the

U.S. military’s global communication network ACAN (Army Command and

Administration Network) was rent asunder between the end of WWII and the

beginning of the Korean War, post-Korea the newly named and established

Defense Communications Agency decided to maintain the global communications

network then in place, and even expand this worldwide, long-haul system to

provide still greater, secure communications. Thus, for the first time in

the nation’s history the president, the secretary of defense, the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, government agencies, and the military services, not to

mention America’s diplomats abroad, had access to a fully integrated,

secure, global communication network at the time the Vietnam War got

underway.

As to how this network got built, under orders from the

DCA the Signal Corps set about integrating what was left of the former ACAN

system with the new network elements put up during the Korean War, and any

other odd long haul network pieces that could be found laying around,

bringing them all together into an expanded global network. As a new network

it was titled the Strategic Army Communications Network (STARCOM). Yet while

this effort proceeded smoothly and the network came on line as required, a

new wrinkle in how the Signal Corps did its job was sneaking slowly into the

process… a wrinkle that would have a profound effect in a few years when the

Vietnam War got underway… and an even more profound effect by the time this

precedent percolated its way down to the War in Iraq.

What was that wrinkle? The answer was that it was

the partial contracting of the task of building STARCOM to America’s

industrial sector: the defense industry. While at the time and on the

surface this new approach of contracting military work to civilian companies

seemed risk averse and a smart way of getting around the effects of the

downsizing of the military at the end of the Korean War, behind the scenes

and underneath it all a dangerous precedent was being set that would live

with the Signal Corps forever. Worse, this new precedent and approach would

inexorably expand and extend itself across all of the branches of the

military, down to today.

Thus today, not only are many of the Signal Corps’

communication systems designed by civilian contractors, they are built and

run by them too. Similarly, and perhaps with far greater consequence when

it comes to protecting civilians, NGOs, and U.S. government agency members

in war zones, the Infantry itself has been co-opted into this program,

finding many of its traditional roles in combat zones supplanted by firms

like Blackwater, Greystone, and the other shadow armies that operate within

what is now known as the Privatized Military Industry. It boggles the mind:

America’s Army fighting side by side with shadow armies hired by the

government so that the size of the military can be kept small.

Thus today, not only are many of the Signal Corps’

communication systems designed by civilian contractors, they are built and

run by them too. Similarly, and perhaps with far greater consequence when

it comes to protecting civilians, NGOs, and U.S. government agency members

in war zones, the Infantry itself has been co-opted into this program,

finding many of its traditional roles in combat zones supplanted by firms

like Blackwater, Greystone, and the other shadow armies that operate within

what is now known as the Privatized Military Industry. It boggles the mind:

America’s Army fighting side by side with shadow armies hired by the

government so that the size of the military can be kept small.

Beginning with the government’s decision to

downsize the U.S. military after the Korean War, a cruel joke was played on

both the military and America’s citizens. Under the rubric of saving money,

downsizing, and realigning the Army to fight smaller more mobile wars (a

claim, as we stated above, that is still raised today whenever Congress or

the president sets about cutting the military’s budget), in the late 1950s

to early 1960s the government set about transferring much of the Signal

Corps’ role to civilian industry players.

Thank you Dwight David Eisenhower. Your fear of

the military–industrial complex was heard well. Unfortunately, the solution

to the problem you and the presidents who followed you put in place only

served to turn it from being a problem of budget matters being driven by the

military–industrial complex into one of budget matters being driven by the industrial–military

complex. The same bedfellows, they just swapped places in bed.[5]

For the Signal Corps, this new partnership with

industry proved a double edged sword. On the one hand, because of the long

standing relationships that existed between the Army’s research facilities

at Ft. Monmouth and civilian industry, the Signal Corps had a cordial,

synergistic working relationship with the civilian guys, one of the benefits

of which was nearly immediate access for development purposes to the very

latest in cutting edge technology and products. On the other, the inroads

civilian industry made into the actual running of Signal Corps facilities

put an enormous strain on the type, quality and amount of manpower available

to the Signal Corps itself. After all, if civilians could do the work, what

was the purpose of recruiting soldiers and Officers into the Signal Corps?

What was the purpose of having training schools to turn out troops qualified

to hold the numerous MOSs (reduced to just 17 as of today) that had been defined? Of what

need were Officers if the complement of enlisted men was being downsized?

Strangely, no one seemed to stop and think of how this would all play out if

more armed hostilities broke out. Would the civilians who were running

Signal Corps facilities be expected to ship out and take up residence in a

war zone if war broke out, to build, run and maintain the Signal Corps

facilities needed there? Nah, surely not.

Meanwhile, while the Signal

Corps was evolving once again… this time learning to embrace a new working

relationship with civilian contractors who were snaking their way ever

deeper into the Signal Corps’ operations and management structure... on the

other side of the world life in South East Asia was beginning to go belly

up. As we all know today, the French suffered a humiliating defeat at

Điện Biên Phủ, after which they

promptly withdrew from Indochina and left the U.S. to deal with the mess

they created.

Meanwhile, while the Signal

Corps was evolving once again… this time learning to embrace a new working

relationship with civilian contractors who were snaking their way ever

deeper into the Signal Corps’ operations and management structure... on the

other side of the world life in South East Asia was beginning to go belly

up. As we all know today, the French suffered a humiliating defeat at

Điện Biên Phủ, after which they

promptly withdrew from Indochina and left the U.S. to deal with the mess

they created.

The U.S., seemingly ever solicitous of the French,

decided to keep the "advisory group" (already in Vietnam) in place when the

French left, allegedly to help guide the South Vietnamese Army now that the

French were no longer available to do the job. In this act the Signal Corps

clearly enmeshed itself in the evolving drama; not just taking a role in a

side show foreign engagement, but inadvertently helping to move the show

over the next few years from the wings of the theater to center stage. The reason the

Signal Corps found itself going along for the ride, with one hand on the

steering wheel, was simple: the Vietnamese Army contained a Signal Corps,

and therein existed a ready-made excuse for the U.S. government to maintain

listening posts in Vietnam as well as send more advisors along.[6]

In the end then, at the onset of the Vietnam War

the Signal corps found itself ostensibly teaching operational and logistical

signal matters to the Vietnamese Signal Corps, while in reality it was using

its presence in-country to listen in on regional communications. As modern

day historians, what matters to us is not what the Signal Corps was doing,

but recognition of the fact that the U.S. Signal Corps was one of the first

elements, if not the very first of the U.S. military, to take up an

active role in the Vietnam War. In particular, in a series of steps between

1954 and 1965 the Signal Corps brought in more and more advisers, to the

extent that they were assigned even down to the divisional level and to each

of the Vietnamese Army's military regions.

By 1963 (at the time of Kennedy’s assassination)

the U.S. had more than 16,000 U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam, the

bulk of which were either assigned to or an intrinsic part of the Signal

Corps. Yet among all of them there were no staff level Signal Officers.

Instead, country oversight was handled by the Signal staff at the Pacific

Command in Hawaii. Interestingly, despite this management from afar approach, things

got done. One of those things included a very serious effort on the part of

in-country Signal Corps staff to send their South Vietnamese counterparts to

signals training at Forts Monmouth. Taking a leaf out of the Signal Corps’

training book, a similar effort was undertaken in 1961 when the U.S. sent

400 Special Operations Forces (Green Beret) to South Vietnam to begin

training local ARVN troops in how to conduct what was, for the first time,

called a counterinsurgency war against the Communist guerrillas in

South Vietnam. Historians should mark this point as the time from which the

term counterinsurgency entered the American lexicon. Today one could almost

say that Afghanistan, or perhaps Pakistan, is a synonym for

counterinsurgency.

Looking back now on how the Vietnam War got

started, and the role the Signal Corps played, it seems strange to admit

that the war itself had no beginning. Is that possible? Can America really

get itself into a war that cost it 58,272 KIA, 303,644 WIA, 1,687 MIA, and

866 POWs, but for which Congress and repeated presidents didn’t have the

time or consideration for its military to sit down and declare war on the

enemy? No formal beginning. No formal end. Is that really possible?

One almost begs to ask: what has our country come to when our elected

leaders spend so much effort dissembling the truth about the foreign policy

they are setting... so that it is palatable to the country at large... that

they don’t have the time to declare as a war an undertaking that America's

youth die in by the bucketful?

Looking back now on how the Vietnam War got

started, and the role the Signal Corps played, it seems strange to admit

that the war itself had no beginning. Is that possible? Can America really

get itself into a war that cost it 58,272 KIA, 303,644 WIA, 1,687 MIA, and

866 POWs, but for which Congress and repeated presidents didn’t have the

time or consideration for its military to sit down and declare war on the

enemy? No formal beginning. No formal end. Is that really possible?

One almost begs to ask: what has our country come to when our elected

leaders spend so much effort dissembling the truth about the foreign policy

they are setting... so that it is palatable to the country at large... that

they don’t have the time to declare as a war an undertaking that America's

youth die in by the bucketful?

Back in those early days, for those on the ground

in Vietnam, with or without a formal beginning, things moved inexorably

towards a hot war. Incrementally, in a series of steps between 1950 and

1965, America found itself engaging in combat with the North Vietnamese.

- - -

One would have thought that this slow march to war

would have given the U.S. military plenty of time to prepare. But that

wasn’t the case, although not through the military’s fault alone. To prepare

for war requires three key things: knowledge that it will happen, plans as

to how the war should be prosecuted, and the money to secure the resources

to prosecute the war as planned. Without a formal declaration of war from

Congress, the funds needed to expand the military to undertake and win this

oncoming war simply did not exist. For the Signal Corps, this meant that as

the French left the country and took along the American supplied signal

equipment that had been given to them, there were no longer any systems in

place with which to tie the country together… nor any money to acquire what

was needed. So again, as in the run up to the Korean war, the Signal Corps

found itself cannibalizing signal facilities around the world in an effort

to build a communication network that could support armed conflict. And

since Japan had already been stripped to support Korea, that left only

Europe as a warehouse from which to pilfer signal equipment to build what

was needed in South Vietnam.

For the South Vietnamese government in power, the

precarious situation it was in only became more obvious—even if it could

rein in the crony capitalism, elitism, and corruption that was endemic in

the country, without a telecom and radio infrastructure with which to reach

the populace, it was going to prove near impossible to rally the South

Vietnamese people to a cause of war with the north. The fact was, the

commercial communication networks built by the French lay in disrepair and

ruin after years of inattentiveness, and the South Vietnamese military,

having no communication network of its own to underwrite its own war

effort, was certainly in no position to help the civilian government tie

the country together. No civilian communication infrastructure, no military

communication network to back it up, no military communication network to

use for its own, and no training in the form of combined arms tactics

required to make effective use of a battlefield network in real time combat, all meant that South Vietnam found itself in a real mess as armed

conflict escalated in the early 60s.

The reader can understand then that with this

scenario presenting itself it was only natural that the “wrinkle” discussed

earlier would raise its ugly head again—this time as the only viable

solution to the problem at hand.

And thus it happened; to make available and stand

up an operational communication system to serve the civilian, military, and

government needs of South Vietnam, the Signal Corps turned to and hired

contractors to construct a regional in-country network. In simple English,

the military downsizing that Congress and the president

mandated on the U.S. Army at the end of the Korean War forced the Signal

Corps to enter this new war with civilian contractors doing the better part

of its job for them. And in short order this first step was followed with a

similar outsourcing of the Signal Corp’s mission to contractors that

designed, built, and in many cases operated parallel networks in Cambodia,

Laos, and Thailand.

The first of these efforts occurred in May 1960,

when Page Communications undertook to build what was called the Pacific

Scatter System,[7] a telecom and data network

designed to serve the Army by linking the Philippines with Hawaii. Following

a course of 7,800 miles, it leapt along a chain of islands and countries

stretching from the Philippines to Guam, Midway, and on to Hawaii. Linking

South Vietnam to the Philippines was accomplished via a portion of the

military’s Strategic Army Communications (STARCOM) network, which was

terminated at Phu Lam (Phu Lam translates as Rich Forest), outside of

Tan Son Nhut. To complete the track, Hawaii was linked to the U.S. at Davis,

California, via circuits that were originally part of the old ACAN network…

yet another ironic example of how a once important piece of the U.S.’s

global communication network was taken out of service because Washington

dictated that the military be cut back at the end of one war, only to find a

few years later that the systems taken down had to be hastily rebuilt to

serve again when the next war popped up.[8]

- - -

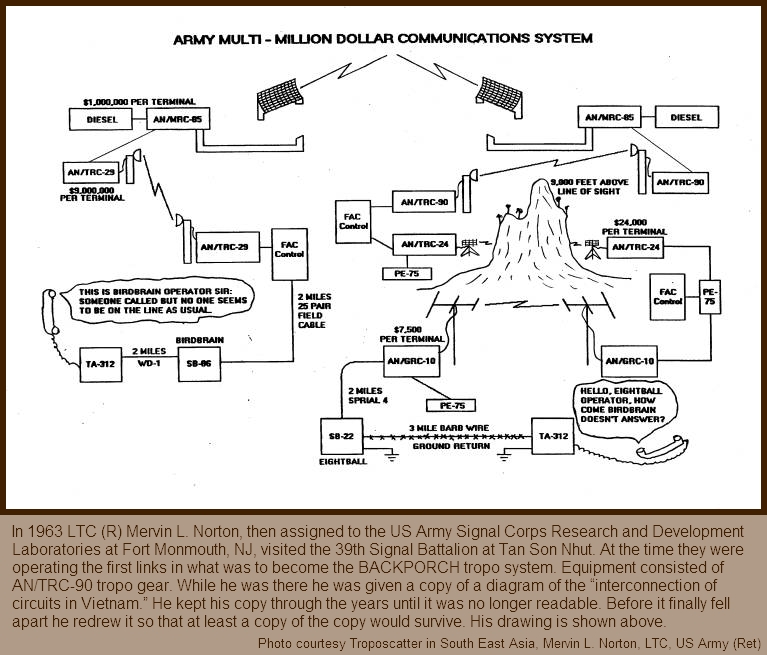

With the Pacific Scatter System in place, in 1962

Page Communications was awarded another contract (by the Secretary of the

Air Force), this time to install a network called BACKPORCH. BACKPORCH was

eventually to be a 72 channel, AN/MRC-85 Tropospheric Scatter system, with terminal

sites at Da Nang, Nha Trang, Phu Lam, Pleiku, Qui Nhon, and Ubon, Thailand.

In its early days however it started out with AN/TRC-90 tropo euipment.

Why did the Air Force contract for the system instead of the Signal Corps?

Again, the primary reason was that the Signal Corps' budget had been cut back so much

that it didn't have the funds

to build the networks needed

to handle combat operations on the ground. Instead, equipment had to be

scavenged from other places and other services.

Cost wise, for the Air Force, it was a good decision, as the

BACKPORCH contract was for only $12 million and that included Page

operating and maintaining the system for a year. For those Signal Officers

who served in Vietnam but may not remember BACKPORCH, while you may not

remember it well, you surely saw it, as BACKPORCH was the beast that caused

all of those huge 60 foot “billboard” antennas to be placed all over the

cities listed above, the mountain tops around them, and the rest of the

country too. Perhaps the most important part of Vietnam’s overall

battlefield, combat, area, and base camp communication net, BACKPORCH made

it possible for standard Army short range multichannel radios to be

connected literally from any active field combat area into the entire

country wide network, covering all of the I, II, III and IV Corps Tactical

Areas.

Unfortunately, while all of this was going on the

Philippines-to-Vietnam portion of the STARCOM network set up by Page was

proving to be a problem. STARCOM's radio circuits suffered from constantly

fading signals, proving unreliable in the steamy, stifling environment of

South Vietnam’s tropics. Needing something more dependable, the Signal Corps

requested approval to supplement STARCOM with an underwater military cable.

In 1962 the Joint Chiefs finally approved this request, with the

construction of the new WETWASH cable system… again contracted to Page

Communications, since the DOD had long since stripped the Signal Corps of

its cable laying ships... being started shortly thereafter.

WETWASH linked South Vietnam to Clark Airbase, at Luzon,

in the Philippines. However, as it would take time to complete WETWASH, an

alternative 60 channel tropo scatter bridging link was requested by the

Signal Corps, to try and connect South Vietnam to the rest of the world via

still another route. This bridging link was designed and built by Philco,

and linked Vietnam at Phu Lam to Bang Ping (near Bangkok), Thailand. At the

Thailand end it was integrated with additional radio links to take it from

Bang Ping to both Pakistan and Okinawa, and then on to the rest of the

world.

Sadly, the Philco tropospheric scatter bridge proved to

be as unreliable as Page’s STARCOM link, to the point that the Signal Corps

finally decided to take things into its own hands by replacing Philco’s work

with a new link designed and installed by the 1st Signal Brigade, instead of

yet another outside contractor. This link reconfigured the Philco approach

by relocating the Bangkok terminal to Green Hill in Thailand, and the Saigon

terminal to Vung Tau Hill. Not too strangely, it worked, perhaps because it was designed by junior level Signal Corps Officers with far less

training and far less compensation than the well paid engineers at Page. Either way, when the Signal Corps took matters into its

own hands, the work got done, and what was done worked. From these new

locations the circuits were then brought into both Bangkok and Saigon via

microwave links.[9]

In the end, while it took time for the lesson to be

learned, the U.S. military got the message that while outsourcing to

civilian contractors might be expeditious, if you wanted to get the job done

to the point that the communication links actually worked under rigorous

combat and environmental conditions, what the Signal Corps had to do was do

it itself. Unfortunately, and here again we are beating a dead horse, while

the Signal Corps seemed to have learned this lesson, Congress and the

president seemed not to, as shortly after the Vietnam War was over, budgets

cuts again tore into the Signal Corps’ ability to maintain and man the

global network it had so rigorously built.

By 1965 all of the kinks had been worked out of the

Vietnam-war-zone-to-the-rest-of-the-world communication system, with the

troops in the field finally being able to depend on multichannel radio relay

equipment to complete what were in fact intricate interconnections, tying

together all manner of VHF, UHF, microwave, tropospheric, ionospheric,

satellite, and undersea cables. Unlike in previous wars, the network put in

place allowed combat commanders on the ground to have instant access from

the field through standard field radios to anyone they might wish to talk

to, from FACs in the field, to Arty at fire support bases, to Westmoreland’s

HQ, any pilot sitting on any aircraft carrier in the entire Navy, all the

way up to the president himself. With an effective combat communication

network now in place, unit mobility greatly improved, allowing commanders to

finally let loose with their Hueys, using them to full advantage in taking

the fight to the Viet Cong and NVA. Perhaps best of all, having moved far

beyond the days of field commanders having to depend on strung wire to

communicate with, commanders could now move and shoot at any time they

wanted, without losing communications for a minute, even while they were en

route to their new positions.

Interestingly, a key part of the mobile capabilities the

Signal Corps delivered came about not because of the fancy long haul links

running over the tropo and other networks set up by the outside contractors,

but by a simple airborne FM relay system set up by Signal people in units

such as the 13th Signal Battalion. For example, in trying to meet

the needs of the 1st Cavalry Division, their client, the Signal guys in the

13th Signal Battalion came up with the idea of mounting radios in fixed-wing

aircraft and then circling those aircraft at 10,000 feet over the 1st Cav’s

daily battle area. By doing this the 13th was able to set up a method for

retransmitting messages between widely dispersed combat units on the ground.

Through this simple expediency the LOS limits and electro-magnetic

absorption effects of the triple canopy jungles on PRC-25s could

be overcome, effectively extending the PRC-25’s range from around 5 miles to

over 60. When the word got out as to what the 13th Signal Battalion had

done, Signal units throughout Vietnam found themselves beseeched with

similar requests by battalion and brigade commanders to help them set up

their own helicopter borne command centers, equipped with radio consoles and

no-nonsense solutions that would make a ham operator cry with envy.

Overall then, as 1965 unfolded commanders found that the number of problems affecting the Signal

Corps’ ability to stand up a solid communication network had been

dramatically reduced, if not completely overcome. Sure, there were still problems with not enough

circuits, but this was more a matter of a lack of available resources

stemming from the downsizing the Signal Corps took after the Korean War

than it was due to technical problems. Overall, traffic was flowing

smoothly, albeit a backlog was beginning to develop.

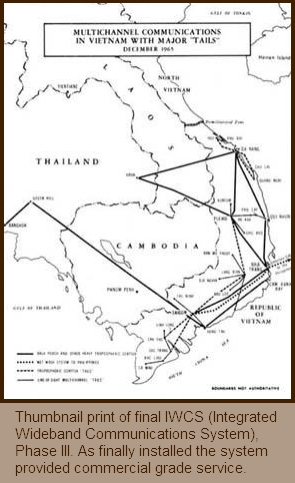

To make sure the backlog did not get out of hand, plans

were made to design and build a base theater network. The network would

involve a wide array of routing and transmission methods that would

reinforce the simple approaches used in cases like the retransmitting

aircraft mentioned above, with a more modern and well integrated battlefield

communication network. Known as the Integrated Wideband Communications

System (IWCS), the design was to blend automatic telephone, teletype, and

data systems with coastal undersea cables, and integrate all of these with

the BACKPORCH and WETWASH systems. The IWCS, designed to serve the Vietnam

battle space as its first priority, would then be integrated into the global

Defense Communication System.

To make sure the backlog did not get out of hand, plans

were made to design and build a base theater network. The network would

involve a wide array of routing and transmission methods that would

reinforce the simple approaches used in cases like the retransmitting

aircraft mentioned above, with a more modern and well integrated battlefield

communication network. Known as the Integrated Wideband Communications

System (IWCS), the design was to blend automatic telephone, teletype, and

data systems with coastal undersea cables, and integrate all of these with

the BACKPORCH and WETWASH systems. The IWCS, designed to serve the Vietnam

battle space as its first priority, would then be integrated into the global

Defense Communication System.

With IWCS in place, things for the Signal Corps became

much less dramatic as the war moved forward. By the time of Tet, everyone

knew their place, signal links were humming, and work progressed almost

without concern as Signal Corps troops went about their daily jobs. Even Tet

turned out to be merely a speed bump to the Signal Corps’ daily activities,

for while 10 of the IWCS signal sites were hit during Tet the damage they suffered

barely affected the “up time” of the network.

Yes, problems with personnel did exist… such as a

shortage of trained operators to run tropospheric scatter terminals.

However, in most cases solutions could be found. Of interest again is that

even in these cases where problems did exist—one more time everyone—they

existed because of the downsizing of the Signal Corps at the end of the

Korean War.

For example, while it was understandable that signal

schools could not produce qualified graduates fast enough, what wasn’t

understandable was why the Signal Corps could not reassign already qualified

personnel sprinkled around the world, from where they were to where they

were needed in Vietnam. The reason was that during the post-Korean War cuts,

the section of the Signal Corps that tracked personnel assignments in relation

to their MOS qualifications had been cut. Thus, since the records of

previously trained personnel no longer existed in a format where they could be

cross linked to current assignments, it was impossible to either recall

those people who had left the military to active duty, or find and reassign

them if they were still on active duty.

Adding to this difficulty, regulations at the time

prohibited the involuntary reassignment of military personnel overseas for

two years. And while this was eventually reduced to 9 months for specific

skills, the only viable solution to the problem was to make it worthwhile

for an enlisted man to “re-up” when his tour of duty was over. Thus, many a

Signal Corps EM found himself with a little extra cash in his pocket as the

DOD offered ever increasing pay and reenlistment bonuses to both recruit and

retain the skilled, combat hardened soldiers the Signal Corps needed.

- - -

In early 1966 General Westmoreland created what was

called the I and II Field Forces. These corps-sized headquarters were

assigned the task of overseeing operations in the II and III Corps Tactical

Zones [Editor’s Note: why the numbers don’t match, we don’t know… but they

don’t]. At the time, II and III Corps Tactical Zones were seeing the

heaviest fighting and were in the greatest need of additional oversight.

Each of these Field Forces was assigned a Signal

Officer, along with a Signal Battalion. To make certain that these two

Signal Battalions shared information among themselves and with the rest of

the Signal Corps’ combat area commanders, as well as coordinate and improve

their own command and control of signal operations based on shared knowledge

of what was happening in other tactical zones, in the spring of 1966 the

Signal Corps created the 1st Signal Brigade.

Once created, the 1st Signal Brigade grew like Topsy.

This new command was the first TOE brigade in the Signal

Corps’ history, holding within its arms all of the signal units in Vietnam

except those that were intrinsic and organic to tactical units. As a unit,

the 1st Signal Brigade consolidated all Signal units above the Field Force

level into one command, essentially merging both tactical and strategic

communication functions throughout the entire Vietnam combat area.

This new command was the first TOE brigade in the Signal

Corps’ history, holding within its arms all of the signal units in Vietnam

except those that were intrinsic and organic to tactical units. As a unit,

the 1st Signal Brigade consolidated all Signal units above the Field Force

level into one command, essentially merging both tactical and strategic

communication functions throughout the entire Vietnam combat area.

To make sure that each of the Tactical Zones were

properly managed, the 2nd Signal Group was made subordinate to the 1st

Signal Brigade and given command over Signal operations in the III and IV

Corps Tactical Zones. Offsetting this, the 21st Signal Group was given

authority over Signal operations in the I and II Corps Tactical Zones.

Finally, in early 1967 the 160th Signal Group was added as a commanding

element with responsibilities for Signal operations in the Saigon and Long

Binh areas, with the 29th Signal Group in Thailand also being added to the

1st Signal Brigade, with responsibility for the flow of communication

between the two countries.

By the end of 1967 the United States had committed

nearly 500,000 troops to the Vietnam War. The Army provided about two-thirds

of the total, including seven divisions and two separate brigades. The 1st

Signal Brigade itself was comprised of twenty-one battalions, organized into

five groups. Its strength peaked at 23,000 men in 1968, the majority of

which served in one or another of the roughly 200 key signal sites

spread throughout South Vietnam. Yet while they were posted to Signal Sites,

that didn’t mean they weren’t in the thick of the fighting. Signal Sites,

while strategically located for the purpose of providing communication, were

little more than forward bases stuck in the middle of enemy territory. By

the summer of 1968 enemy attacks on signal positions numbered an average of

eighty per month.

In addition to American forces, Australia, New Zealand,

South Korea and Thailand all contributed units, as of course did South

Vietnam, bringing the total manpower engaged to well over a million. Unlike

the situation during the earlier Korean War, however, the U.S. commander had

no command authority over any of these friendly troops. In researching this

article we attempted to see if a study had ever been done on whether the

American commander’s lack of command authority over the entire complement of

troops available in Vietnam had any impact on the outcome of the war. We

were unable to find any such study… but one wonders what the result would be

today if such had been the case.

Most readers know how the Vietnam War ended, so we won’t

pursue here either how it was conducted nor the interplay of politics in its

ending. If justice is to be done to these topics, space far larger than that

available on this website would be needed. Instead, we will keep our focus

on the Signal Corps.

Looking at just the Signal Corp side of things, as the

war wound down the size of the 1st Signal Brigade decreased in lock step

with the political mandates dictating the rate and type of withdrawal. By

1972 the 1st Signal Brigade’s strength stood at less than 2,500 men. On 7

November 1972 the brigade headquarters left Vietnam and transferred its

colors to Korea. The 39th Signal Battalion, the first Signal unit to arrive

in Vietnam, became the last to leave. Fittingly, as its final wartime

mission the battalion supported the international peacekeeping force that

monitored the troop withdrawal and prisoner exchange. The unit departed

Vietnam on 15 March 1973, almost eleven years to the day after its first

elements had arrived.[10]

By the summer of 1973 the United States had completed

the withdrawal of its combat troops.

Lessons Learned

In terms of lessons learned and changes suffered,

clearly the Signal Corps that fought the Vietnam War was unlike the Signal

Corps that

fought the Korean War, or certainly the war before that. The only thing all

of these had in common was that they all shared the same name. Except for

the most minimalist stating of its mission, everything about it, including

its mission, had changed. As an example, the

Chief Signal Officer had disappeared from the organizational chart and been

replaced by a Chief of Communications-Electronics. While a nice modern title

befitting of a civilian executive, the position held absolutely no

operational responsibilities.

Later, as war activities increased, this move to strip

the Signal Corps of operational command over its own people and assets

proved to be a disaster. In simple English, the abolition of the Chief

Signal Officer's position (in 1964) left the Signal Corps chain of command

in near total disarray. The lack of coordination that ensued forced General

Westmore-land (in July 1965) to disband the U.S. Army Support Command,

Vietnam, (former-ly the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam), and create the

U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV).

Later, as war activities increased, this move to strip

the Signal Corps of operational command over its own people and assets

proved to be a disaster. In simple English, the abolition of the Chief

Signal Officer's position (in 1964) left the Signal Corps chain of command

in near total disarray. The lack of coordination that ensued forced General

Westmore-land (in July 1965) to disband the U.S. Army Support Command,

Vietnam, (former-ly the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam), and create the

U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV).

USARV’s purpose was to try and undo the damage that had

been done by McNamara and his boys working with Congress to gut the

military, in order to save money. It wasn’t the money part that worried

Westmoreland, it was the lack of command control over the people deciding

the tactics and fighting the war.

Westmoreland, by creating USARV, was able

to once again take under the military’s wing operational control over all

military people in Vietnam (except for the advisers), and their assets. The

reader should note however that while Westy’s little trick helped things in

Vietnam, it did nothing to change how the military worked across the rest of

the world. Even so, from the Signal Corp’s viewpoint, thanks to Westmoreland,

the Signal Officer on the USARV staff was once again able to take

responsibility for and command over the Army's tactical signal operations

and personnel, with long-haul communications coming under the purview of the

Strategic Communications Command.

In addition to fighting to gain control over its own

tactics and people, the Signal Corps had to relearn in Vietnam what it was

like to fight a war that did not conform with what Army planners had thought

the next war would be like when the Korean War ended. Strangely, even though

the use of nuclear weapons was approached and retreated from time and again

in Korea, with nuclear weapons never being used, at the end of the war Army planners

were convinced that in the post-Korean War period the next conflict would be

a nuclear one. This of course meant one would be fighting across a nuclear

battlefield. And this of course meant that the Army needed to be reorganized

yet again, to accommodate what was thought would be highly fluid, front-line

centric, combat conditions in the midst of nuclear fallout.

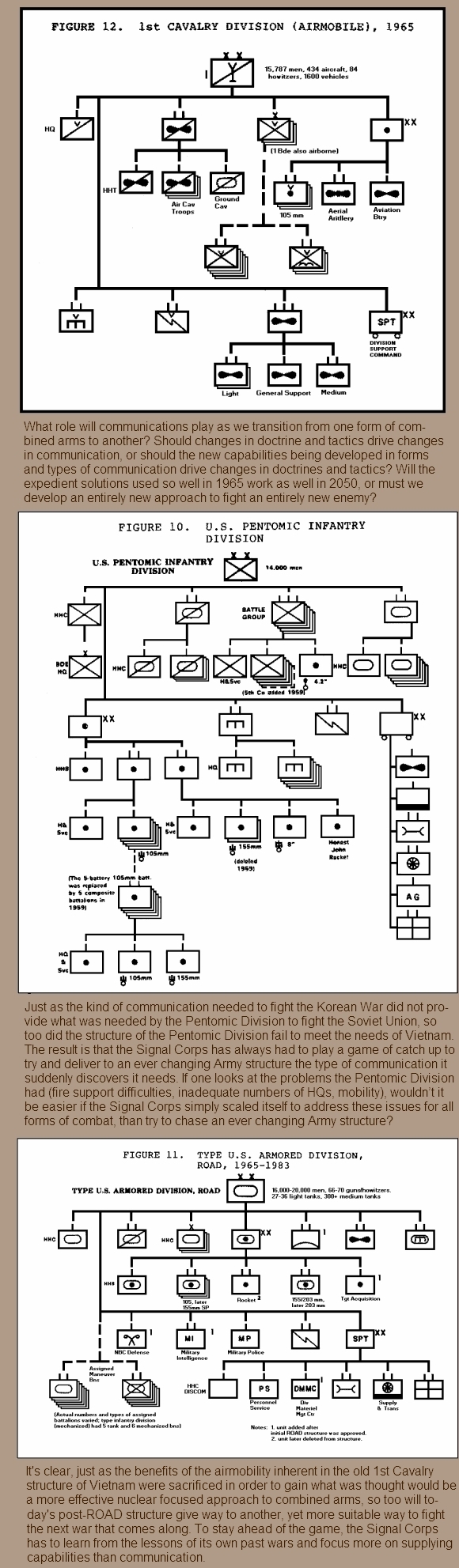

Accordingly, concepts for combat operations, like the

"Pentomic Division", ROCID, and ROAD were developed and put in place. These

forms of tactics were designed to support a fluid, aggressive, conforming

type of combat. To support this, the Army equipped itself with tech-nology

that matched the tactics. Thus, as the Vietnam War got underway the Army

found itself with equipment like the Davy Crockett rocket, an ingenious bit

of portable armament sporting an atomic warhead—clearly

something useful on the plains outside of Moscow, but totally useless in the

jungles outside of Dalat. Instead, it became clear that since the troops in

Vietnam faced guerrilla warfare in jungles and rice paddies, what was needed

were weapons suitable to this environment, as well as tactics that matched

both the environment and the enemy. In particular, since the enemy proved

slippery, what was needed was a full reorganization to allow the Army to

mount expeditions from fixed bases to both engage and fix the

enemy.

For the Signal Corps this meant quickly developing a

doctrine that supported rapid responses by the combat arms, via the use of

communication equipment that, in the field, was small, lightweight,

portable, and reliable, but back on base was supported by fixed-base

communication via multiple forms of transmission, usually depending on large

antennas and heavy equipment. Flexibility in deployment and mission support

became the first of many lessons that the Signal Corps took from Vietnam.

Adding to this, since a typical divisional signal

battalion in Vietnam ended up covering areas of 3,000 to 5,000 square miles, compared

to the 200 to 300 miles that was expected in a ROAD type of

conventional-cum-nuclear war, Signal units found themselves jostling to come

up with the equipment needed. In this case, the problem was not lack of

funds or poor planning, it was that the TOE allocation a Signal unit had was

based on a design intended to provide for a much smaller footprint

containing far fewer combat troops in need of support. When one looks back

today on Rumsfeld's plan to slim down the Army and make it much more mobile

and responsive to asymmetric warfare, or that of the Obama Administration

today, this problem is the first one that comes to mind. Slimming down the

complement of personnel is one thing, but are you then going to slim down

the amount and type of equipment available too? If so, what will you do when

you find yourself dealing with a 5,000 square mile combat area that, while

it does not need a lot of manpower to keep it operational from a technical

perspective, needs tons of equipment widely dispersed and aggressively

defended by lots of people in order to keep it up and running?

An example of this can be seen in the 518th Signal

Company, a unit this author was assigned to as X.O. towards the end of his

tour of duty in Vietnam. The 518th, a company formed to provide tropo and microwave

communication throughout the entire III and IV Corps Tactical Zones, was

supporting some 14 microwave sites, 4 tropo sites, and a ton of smaller VHF

and UHF sites when I was there. Manpower wise, it grew far beyond the normal

complement of 80–225 odd people that a typical Signal Company might normally

house. At the time of my service the 518th had more than 400 troops assigned

to it.

An example of this can be seen in the 518th Signal

Company, a unit this author was assigned to as X.O. towards the end of his

tour of duty in Vietnam. The 518th, a company formed to provide tropo and microwave

communication throughout the entire III and IV Corps Tactical Zones, was

supporting some 14 microwave sites, 4 tropo sites, and a ton of smaller VHF

and UHF sites when I was there. Manpower wise, it grew far beyond the normal

complement of 80–225 odd people that a typical Signal Company might normally

house. At the time of my service the 518th had more than 400 troops assigned

to it.

Lesson wise then, Vietnam taught the Signal Corps that not only did

it have to be flexible when it came to the type, design, and purpose of the

communication equipment it filled its coffers with, but it also had to learn

how to command a troop complement far larger and more greatly dispersed than

anything encountered in any previous war. In Vietnam, if a Company Commander

wanted to check on the status of his troops, as in the 518th where my men

were spread over an area the size of Connecticut, it involved a lot more

than merely walking out of my Nha Trang office and sauntering through the

barracks or mess hall before heading to the Duy Tan bar for the night.

Instead, it involved up to two months of travel to visit all of the signal

sites. Often times this forced me to allocate less than a day at each,

sitting and talking with no more than a handful of men for an hour or so

until the chopper pilot impatiently signaled me that he had to move on to

his next stop. Surely these men, sitting at a remote signal site

experiencing combat every 3 to 5 days, deserved far more than a visit from

their commander every 6 - 8 months, one that gave them just an hour or

two of face time at that.

That's what happens when Congress takes a dull axe to

the Army's budget, and Pentagon planners then make TOE decisions based not

on the wars that we fight, but the ones the civilian appointee heading the

DOD thinks may happen next. Better to over compensate in terms of types and

quantities of military communication and armament systems than to try and

outfit your military with some constantly changing concept of what the next war will

be like and who it will be against. Strategic planning is an unscientific

science. It doesn't always work. Rumsfeld himself, who was not a bad

Secretary of Defense in his own right, said that the problem with making

decisions based on strategic planning is that the process of strategic

planning is far from an exact science. He said that the very first rule for

strategic planning is to precisely define one's goals. In his

latest book Known and Unknown, A Memoir, he said "Setting clear

goals may sound obvious, but it is remarkable how rarely governments..." do

it. Instead they spend their time thinking of "options or courses of

action."

He

goes on say that if you want any chance of success in using strategic

planning as a base from which to make policy decisions, you need to

prioritize your goals. He makes the point that without knowing "which goals

are the most important, one ends up with little more than a wish list...".

Looking at the government's latest plans to cut the military's budget while

at the same time reorienting the military to fight Naval battles with China

and Iran, one has to wonder if this is not the very kind of wish list

thinking that Rumsfeld says comes out of poor strategic planning. After all,

what is the most important goal here? Is it to cut spending in the military,

or win the next war we get into. One could be forgiven for thinking that

these are two mutually exclusive options.

He

goes on say that if you want any chance of success in using strategic

planning as a base from which to make policy decisions, you need to

prioritize your goals. He makes the point that without knowing "which goals

are the most important, one ends up with little more than a wish list...".

Looking at the government's latest plans to cut the military's budget while

at the same time reorienting the military to fight Naval battles with China

and Iran, one has to wonder if this is not the very kind of wish list

thinking that Rumsfeld says comes out of poor strategic planning. After all,

what is the most important goal here? Is it to cut spending in the military,

or win the next war we get into. One could be forgiven for thinking that

these are two mutually exclusive options.

In the end, the Vietnam War proved to be a study in

contrasts, teaching the U.S. government one thing, the military another, and

the Signal Corps still another. As for the enemy, the lessons they learned

have been recorded and taught to every tin

pot dictator and despot ruler

on earth… giving each a way to poke its finger in our

eye at any time they want, without fear of a military defeat. From Iran to

Venezuela, North Korea, Pakistan, Syria, and even Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan

and others, many nations have decided that while America’s military might be

strong, a) its superior firepower can be matched in the field with

rudimentary arms backed by fanatical fighters, b) America’s national debt

and deficit will not allow it to fight long enough to win a prolonged war,

c) our politicians will cut and run at the first sign that our populace has

lost interest in the war, and d) you can count on our populace to lose

interest and cry for an end to any war in, oh, about 2 – 3 years.

As for our own government, especially as regards how it

treats its military, the U.S. government seems not to have learned any of

the important lessons stemming from either WWII, Korea, or Vietnam. In this

author’s view, they continue to make the same mistakes in trying to

micromanage the military as they have in each of these wars, especially once

a war ends, cost cutting battles begin, and Congressmen try to hive off ever

larger pieces of the military’s budget to support bridge construction in

their home district.

Politically, in relation to how our government addresses

those foreign countries that wish us ill, they seem again not to have

learned much. Compare if you will the current president’s comments in 2008

on Iran with those of Kissinger on Vietnam in 1972. In 2008 President Obama

stated in a speech in Portland, Oregon, that Iran doesn’t “pose a serious

threat to us” because, by his reckoning, “tiny countries” with small defense

budgets can’t do us harm. Kissinger matched this idiocy when in 1972 he

stated on his return from his famous Paris peace talks “peace is at hand.” I

suppose that if you consider having the U.S. Navy taunted by speedboats in

the Strait of Hormuz from a soon to be nuclear power not a serious threat,

or the death of 58,272 American soldiers in a war that our government turned

its back on for a last minute “peace” so that politics could go on as usual

before the next presidential race, then both of these people must be

right.

Politically, in relation to how our government addresses

those foreign countries that wish us ill, they seem again not to have

learned much. Compare if you will the current president’s comments in 2008

on Iran with those of Kissinger on Vietnam in 1972. In 2008 President Obama

stated in a speech in Portland, Oregon, that Iran doesn’t “pose a serious

threat to us” because, by his reckoning, “tiny countries” with small defense

budgets can’t do us harm. Kissinger matched this idiocy when in 1972 he

stated on his return from his famous Paris peace talks “peace is at hand.” I

suppose that if you consider having the U.S. Navy taunted by speedboats in

the Strait of Hormuz from a soon to be nuclear power not a serious threat,

or the death of 58,272 American soldiers in a war that our government turned

its back on for a last minute “peace” so that politics could go on as usual

before the next presidential race, then both of these people must be

right.

For the Signal Corps, there were lessons to be learned

from Vietnam. And for the most part, at least from this distance of

retirement, it appears that the Signal Corps has done its best to learn and

apply these lessons, in spite of the rearguard action it has had to fight all

these years, just to hold its own.

While we have talked of politics and process as areas

of lesson learning, another important lesson learned from Vietnam has to do

with the impact of technology on a modern Army's ability to fight against a

regressive society. Take the issue of the level, type and quality of

communication available to both sides.

In Korea America experienced for the first time the

impact of fighting against an enemy on horseback and mules, communicating

via flags and whistles. Yet strangely, horses and mules aside, the

difference in communication capabilities had little impact on how the war

was fought or its outcome. In Vietnam the same disparity in communication

capabilities existed, but the impact was far greater. Why?

Part of the answer lies in the fact that in Korea it was

a man to man fight, while in Vietnam the fight was via a proxy: the local

villagers. If you are fighting man to man all you have to do is beat the

other guy and the battle is over. If however the fight is really about the

hearts and minds of the local villagers, and the other guy is rallying the

local villagers every night after your pull in your pickets and lock your

front gates, you had better find a way to "communicate" that returns data

not about what the enemy is saying, but what the villagers are thinking. The lesson learned

then is that while the communication available on each side of a battle line

might show a

massive disparity, this doesn't mean that the enemy is at a disadvantage.

All the enemy has to do to make up for any weaknesses it suffers in lack

of technology or communication capacity is to simply change the form of

battle it engages in. Battling via proxy fighters is the quickest and

easiest way to do this, as is fighting a guerilla war. And if one thinks this lesson hasn’t been learned by

North Korea today… or even Iran, then one is sorely mistaken.

In primitive societies such as those of Vietnam, North

Korea, or Iran, enjoying effective means of secure combat area communication

is virtually unknown. On our side, while we may enjoy the most sophisticated

signaling systems ever seen on the battlefield, their utility is of little

value if they do not support a better means to gather information about the

enemy, his position, intentions, status, and pattern of methodological

behavior, and transfer that information in the form intelligence to the

troops on the ground. Advanced systems such as satellites, tropospheric

scatter, FM radios, and fiber optics are of little value if this goal is not

achieved in its entirety.

In primitive societies such as those of Vietnam, North

Korea, or Iran, enjoying effective means of secure combat area communication

is virtually unknown. On our side, while we may enjoy the most sophisticated

signaling systems ever seen on the battlefield, their utility is of little

value if they do not support a better means to gather information about the

enemy, his position, intentions, status, and pattern of methodological

behavior, and transfer that information in the form intelligence to the

troops on the ground. Advanced systems such as satellites, tropospheric

scatter, FM radios, and fiber optics are of little value if this goal is not

achieved in its entirety.

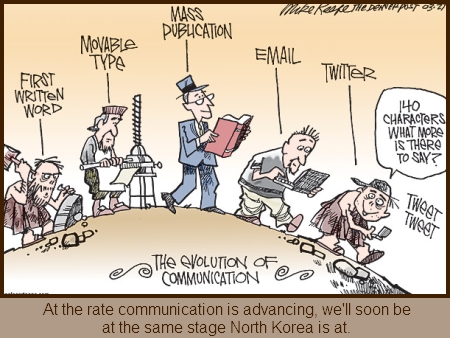

One of the lessons of Vietnam for the

Signal Corps then should be that it needs to both broaden the number and type of forms

of communication technology available to it, as well as expand its role in

the war game itself, to vet the data gathered and deliver it in the form of

actionable intelligence to the war fighters, in sub-real time responses. One can see the need for this latter point because, strangely, the

need to be able to do these things in ever shortening degrees of real time

activities is in direct proportion to the enemy’s increasingly sparing use

of any form of communication. That is, the more the enemy goes quiet, the

more imperative it is that Signal Corps systems and processes are able to

work at a faster speed. Harking back to the Air Force’s lessons from the

Korean War, one could say that the overwhelming technological superiority

the Signal Corps holds becomes of little value if it cannot close its

OODA

loop faster than the enemy retreats from the use of technology. In other

words, decision making in the 21st century will take place under conditions

of ambiguity and hyper-speed in information: in a word, complexity. The

Signal Corps must adapt its capabilities to support this new form of

communication.

In closing, while as the reader can see from some of the

comments in this article, a modicum of ill feeling and bitterness still

remains in those who fought in Vietnam… at least with regard to how the

Vietnam War was brought to a close. Nevertheless, there is little argument

that the U.S. Army Signal Corps performed its mission admirably. It got the

message through.

As stated

about the Vietnam War

in Getting the Message Through, A Branch

History of the U.S. Army, “in performing their mission, Signal Corps

communicators sustained relatively heavy casualties, especially among

radiotelephone operators accompanying combat operations. Their vital mission

coupled with their high visibility, [and] the telltale antennas protruding

from the radio sets, made them prime targets.” And while no amount of

rationalization can negate the price these boys paid, it must be said that

in support of their efforts their brother signalmen did their damndest to

put in place and deliver efficient and rapid communications, if only to help

reduce the battle fatalities of our fellow signalmen by speeding up the medical evacuation process.

Among the list of Signal Corps Officers we should pause

to think of for their gallantry in Vietnam is Capt. Joseph Maxwell ("Max")

Cleland, who received the Silver Star. Among those Signal Officers assigned

to closely held signal companies embedded within the Infantry and other

units, several soldiers serving as communicators earned recognition. One of

them, “Capt. Euripides Rubio, Jr., communications officer for the 1st

Battalion, 28th Infantry, posthumously won the award for his gallantry

during Operation ATTLEBORO in Tay Ninh Province in November 1966. During an

attack on 8 November, Rubio left the relative safety of his position to help

distribute ammunition and aid the wounded. When the commander of a rifle

company had to be evacuated, Rubio, already wounded himself, took over.