Three

months ago on our April Home Page we took our government to

task for not giving us Americans enough information before a

war begins to allow us to assess the value of an upcoming

war to our nation’s needs. What we were trying to express is

our viewpoint that as things stand now most Americans are

wholly unable to make an accurate assessment and understand

the implications of an upcoming war sufficiently to fully

understand what kind of commitment our country must make to

that war if we are to win it. What spurred us to look into

this area is the fact that the American public seems to

consistently tire of each war we get into long before it is

able to be brought to a proper end, with the result that our

government and military leaders find themselves rushing to

end a war and “get the boys home” before the public starts

taking to the streets with pitchforks. Obviously, this

sloppy method of ending the wars we fight contributes

greatly to another problem we face: messy endings that leave

the countries we fight in as basket cases stumbling along

for the next 50 years as wards of society, or worse, as a

continuing nemesis to our own country.

What we said the American people needed to know if

they were going to stand behind a new war effort for

“as long as it takes” was what the government and

military leaders who would manage the war thought

about how long the war would last, how much it would

cost in terms of our nation’s treasure, how long our

commitment as a nation must be for, what the final

stage of winding down the war would look like, how

long the final stage would last, what the final

stage's cost would be, and what the world would look

like when all of the stages of the war were over and

done with and the world was at peace again.

Key

among these is the latter point as it applies to

any hypothetical new country we might be thinking of

warring against. That is, what will

that

country look like when our happy warriors come home

and we are no longer spending any money to support

it? Will it be stable and prosperous, enjoying a new

form of participatory government, or will it be an

oozing, war torn abscess of a nation hanging on the

rump of the world for the next 50 years… as North

Korea is and it is increasingly looking like Iraq

and Afghanistan may be too?

As we said then, if we as Americans were to be so lucky as

to actually be briefed on these kinds of things before a new

war gets underway, and also lucky enough to actually have a

President and Congress that has enough respect for the

Constitution to declare a war instead of just segueing into

it with the same insouciance that they apply to forming a

budget, then we might be able to get into one of these wars,

win it, and leave behind a successful, free, peaceful,

prospering country, instead of the kind of mess we see the

world being dotted with today.

Moving from this point to one that

runs parallel to it, in this month’s article we are

concerned with how technology impacts these hot little wars.

That is, what impact does technology have on the outcome of

the kind of wars we are increasingly taking on today? If the

American public is ever to know what to expect when America

next goes to war, it needs to know more than just how many

soldiers and how much money it will cost. It also needs to

know how a war will shape up as it gets underway. And to

know the answer to that, one must know of the impact today’s

technology has on a war's effort, because in the end it is

technology that shapes warfare.

Why does the public have to know how

our technology... more specifically how today's emerging

technologies... affect warfare? Because the depth and

breadth of pain the American public feels in any new war

effort will be in direct proportion to the ability of the

war fighters, on both sides, to leverage the technology they

have access to to their benefit. Simply put: no pain, and

the American public will let the military fight a war

forever, until everyone is satisfied that it has been won

the way it should be; too much pain in too short a time, and

the American public will demand that the war be put to an

end quickly and everyone brought home, regardless of whether

we are winning or not. And just to be clear, in this case

pain does not just mean the loss of America’s sons and

daughters in combat. It also means the kind of damage to

America’s national pride and image that a poorly conducted

war effort can bring (think: Abu Ghraib).

Why does the public have to know how

our technology... more specifically how today's emerging

technologies... affect warfare? Because the depth and

breadth of pain the American public feels in any new war

effort will be in direct proportion to the ability of the

war fighters, on both sides, to leverage the technology they

have access to to their benefit. Simply put: no pain, and

the American public will let the military fight a war

forever, until everyone is satisfied that it has been won

the way it should be; too much pain in too short a time, and

the American public will demand that the war be put to an

end quickly and everyone brought home, regardless of whether

we are winning or not. And just to be clear, in this case

pain does not just mean the loss of America’s sons and

daughters in combat. It also means the kind of damage to

America’s national pride and image that a poorly conducted

war effort can bring (think: Abu Ghraib).

Continuing with our thinking: in our

view, more than any other force, the availability or lack of

availability of technology has a dramatic impact on how a

war is fought, who comes out on top, how long a war must go

on before someone does come out on top, and how effective

post-war governing leaders will be in helping their

country return to peace. One need only look at the impact of

drones on Afghanistan to see what we mean re. technology

shaping war.

When

Afghanistan first got underway effective drone technology

was in its infancy, with many military leaders seeing it

more as a defocusing video side game than a useful piece of

armament to have in their basket of tricks. Now, 11 years

later, drones have become more relevant to the war effort

than ISAF itself. The same might be said for Facebook,

YouTube, Twitter and the myriad other social network

platforms that let the enemy get their word out in ways that

Ho Chi Min could have only dreamed of. Think back to the

viral way in which the Abu Ghraib photos spread around the

world in less than an hour, or the burning of the Korans in

Afghanistan led to over 3 million tweets in 24 hours, and

you will see our point.

Technology has a great impact on warfare, even non kinetic

technology.

[1]

Technology, more than any other

outside force, shapes warfare. In trying to figure out how

effective America will be in fighting any war then, one must

take into effect how well we use technology … both kinetic

and non-kinetic… to fight a war, as well as how well our

enemy uses it.

Bear in mind here that when speaking

of technology we are not talking of the old traditional

forms of technology such as those used for communication

interception and the like. Those forms have been around

since the very first recorded war ever fought—between Sumer

(in modern Iraq) and Elam (a region that is now part of

Iran) in 2700 BC. Instead we are talking about emerging

technologies, of the kind mentioned earlier. These emerging

technologies… like those used in drones, or those used by

Bradley Manning to leak military secrets to WikiLeaks, are

what we are speaking of. Emerging technologies… the kind

that not only shape how a war is fought, but are also shaped

by it.

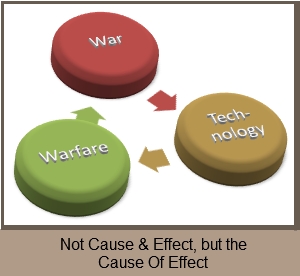

Note again the last part of the

previous sentence. Strange though it may seem, the unique

thing about technology is that while it has a dramatic

impact on a warfare, conversely it is war itself

that shapes technology. One more time: war itself shapes

technology, not warfare. Clarifying this point

then; among the three—technology, warfare and

war—technology shapes warfare but not war, while on the

other hand war shapes technology but not warfare.

If this is true, then we can also

say that military technology is not deterministic. In other

words, just because a particular military technology was

instrumental in winning a war in the past, you can’t assume

that the inevitable consequence of an improvement to this

antecedent form of technology will cause the state of

affairs today to result in another win. Military technology

in and of itself is not deterministic. Rather, it opens

doors as to what can be. Because of this, emerging

technologies that are based on successful antecedents will

not open any more doors for the managers

of war than a form of technology that has not yet proven

itself useful or successful. Regardless of a technology's

past history and evolution, there is no way to determine

whether it will intrinsically spawn a successful form of

usage when applied in a wartime environment. What does

determine the success of a technology is how many of the

doors that technology opens man decides to walk through.

Thus, the more doors a technology opens to possible means

and methods of use, the greater the availability

of and larger number of paths there will be to wartime success.

If this is true, then we can also

say that military technology is not deterministic. In other

words, just because a particular military technology was

instrumental in winning a war in the past, you can’t assume

that the inevitable consequence of an improvement to this

antecedent form of technology will cause the state of

affairs today to result in another win. Military technology

in and of itself is not deterministic. Rather, it opens

doors as to what can be. Because of this, emerging

technologies that are based on successful antecedents will

not open any more doors for the managers

of war than a form of technology that has not yet proven

itself useful or successful. Regardless of a technology's

past history and evolution, there is no way to determine

whether it will intrinsically spawn a successful form of

usage when applied in a wartime environment. What does

determine the success of a technology is how many of the

doors that technology opens man decides to walk through.

Thus, the more doors a technology opens to possible means

and methods of use, the greater the availability

of and larger number of paths there will be to wartime success.

The relevance of all of this to our

discussion of the impact of technology on war is that not

knowing where emerging technologies have their greatest

impact can be dangerous to a war leader; dangerous to the

point of making it possible to lose a war if one is not

careful.

One can see a bit of this happening

in the use of drones in Afghanistan. Clearly, military

leaders now know that a) the plan is that everyone be out of

Afghanistan and home by 2014, b) with only two years to go,

the last thing the American public will stomach is a large

loss of life at this stage of the war, so if the desire is

to wrap it up quickly you might as well scratch combat

operations off the list, c) in a couple of years there won’t

be anyone left in Afghanistan to fight this war with, and d)

in spite of all of this, and regardless of whether we are

there or not, the war will go on for at least another 7 – 10

years anyway, and likely result in something future

historians will classify as another “Vietnam style defeat”

for America.

With this in mind, how can anyone

blame today’s military leaders from turning to drones as

their surrogate fighting force? After all, pretty soon it'll

be all they have left.

This latter point aside, whether they are blamed

or not, unfortunately, drones—or any other form or

combination of emerging technologies for that matter—won’t

help our commanders win the war in Afghanistan. Depending on

technology to solve what couldn’t be solved with boots on

the ground creates in a leader a false chimera not worthy of

his carrying the title Combat Commander.

Why? Because technology shapes

warfare, not war, and especially not its outcome. War, on

the other hand, as we said above, shapes technology.

The important point here is to

distinguish between war and warfare, and the impact

technology has on both of these.

That technology shapes warfare not war is easier to see

today than it was back during WWII, and certainly much

easier than it was during WWI.

Like the air we breathe and the water we drink, it is

unfortunate but true that for as long as Homo erectus has

been around, so hasn’t war. It is timeless and universal.

The fact that our species has used it as a tool to impact

society’s development for over 1.6 million years, since we

first started walking upright, makes one wonder if all of

the cries for peace coming from the liberal left isn’t just

one big waste of time? Does anyone really believe that the

mere act of wanting a world at peace is going to bring one?

Does anyone really think that if one element of society

gives up war, all the others will too? Haven’t the wars

stemming from religious intolerance made the case that man

has found a way to usurp even the most beautiful part of

man’s thoughts—belief in a good and peaceful God—such that

rather than religion being a cause for good, it now has

become a cause for war? Let’s face it, war is here to stay.

If so, then what of technology’s impact on it?

Ahhhh… we got you. You see, that’s a trick question. It’s a

trick question because if one looks at the graphic below,

one will see that technology has no impact on war. Instead,

it’s impact is on warfare.

What’s

the difference, you ask? Consider this: our current

President is busy trying to reduce America’s stockpile of

nuclear weapons. He’s also busy shelving the research Reagan

started into ways and means of shooting down ICBMs and other

offense postured missiles (especially during their boost

stage) and satellites. If our premise here that war impacts

technology, and technology impacts warfare, and warfare

impacts war is right, then doing away with nuclear weapons

or missile defense shields isn’t going to do a darn thing

when it comes to stopping or preventing war. All it is going

to do is impact our ability to fight it when it inevitably

comes.

What’s

the difference, you ask? Consider this: our current

President is busy trying to reduce America’s stockpile of

nuclear weapons. He’s also busy shelving the research Reagan

started into ways and means of shooting down ICBMs and other

offense postured missiles (especially during their boost

stage) and satellites. If our premise here that war impacts

technology, and technology impacts warfare, and warfare

impacts war is right, then doing away with nuclear weapons

or missile defense shields isn’t going to do a darn thing

when it comes to stopping or preventing war. All it is going

to do is impact our ability to fight it when it inevitably

comes.

Look at the graphic and you can see that being without nukes

or missile defense systems won’t deter an aggressor from

attacking… to the contrary, it might even incent one to

attack sooner. But it most definitely will impact how we

fight any such war that an aggressor might start. A weak

military posture invites strong actions against us by those

who oppose us. And if we toss our best technology into the

scrap heap of history, all this will do is multiply the

strong response by those who oppose us by a factor of five

or more. The increase in the strength of their response will

be exponential folks, not linear.

To be clear, by warfare we mean the conduct of war. In other

words, the broil and scrimmage of arms in the field, or the

deployment and management of armed forces in the exercise of

conflict. Warfare entails what we learned of in OCS as

operations, whether or not it involves engaging opposing

forces directly, or via some other organized form of

violence, kinetic, or non-kinetic action.

War on the other hand is little more than a condition. It is

the condition of circumstance that a state or government

finds itself in. While warfare (i.e. the physical activity

conducted by armed forces in the context of war) can

determine the final condition of circumstance that a

government may be saddled with when a war is over, the fact

that a country or people are in a state of war cannot

determine the mode of warfare that is used to impact the

final result of the conflict. Only technology can do that.

So, in the end, if a country wants to have control over the

final state it finds itself in when a war ends, then it has

to develop a credible means to conduct warfare. And if the

desire is to be able to use warfare in a credible manner to

impact the end state of a war, then that same country needs

to master the use of technology to underwrite its mode of

warfare… emerging technology in particular.

By now our astute readers will ask, What about diplomacy?

Can’t it be used to win a war or affect its outcome? Why

only warfare?

Clearly,

the answer is yes, diplomacy can impact the final state of a

war. However, unlike von Clausewitz, we would not say that

“war is an expression of politics by another means,” instead

we would say that politics (i.e. diplomacy) is an expression

of war by another means. In other words, diplomacy, or what

von Clausewitz calls politics, is in reality just another

method of warfare. Our point then being that warfare is the

overarching entity that determines society’s advance, not

politics.

Clearly,

the answer is yes, diplomacy can impact the final state of a

war. However, unlike von Clausewitz, we would not say that

“war is an expression of politics by another means,” instead

we would say that politics (i.e. diplomacy) is an expression

of war by another means. In other words, diplomacy, or what

von Clausewitz calls politics, is in reality just another

method of warfare. Our point then being that warfare is the

overarching entity that determines society’s advance, not

politics.

We say this because in our view the methods of political

control over people that have come and gone through the ages

have had less of an impact on society’s advancement than

warfare has. Everything from dictatorships, monarchies,

empires, and strange things like the old Hanseatic League

through to internal revolutions, anarchy, democracy,

communism, socialism, Marxism, Leninism, Mao Tse Tung's

thought, the teachings of Che Guevera, and much, much more

has been tried. And one by one they have all fallen by the

wayside or failed at giving people what they want. The only

thing that has remained consistent throughout time has been

the use of warfare to gain for a society that which it could

not gain by political means. Unlike politics, warfare has

proven its enduring ability to either protect or restore to

a people the form of society that they wish to live in.

Don’t mistake what we are saying here. We are not saying

that war is good, only that if one looks again at the "Cause

Of Effect" graphic above one will easily see that diplomacy,

politics, and the state a country or society exists in are

all impacted by technology.

This moves us to our next point: understanding what the

impact of technology is on warfare.

Since wording is important in our making our case, let us

say with specificity what we mean by the impact of

technology on warfare. Here we mean that technology defines,

rules, restricts, and demarcates how a war is fought. It

presages how warfare will take place, and once warfare

begins it (i.e. technology) becomes the instrument of

warfare.

If forced to distill all of this into one word, the greatest

impact technology has on warfare is that it alters it.

Referring back to our discussion above about politics and

diplomacy, one can see that if diplomacy is just another

form of technology, then as it evolves it too can impact how

a war is fought. That is, thinking of a new form of

diplomacy as merely an emerging form of an existing

technology, one can see (and even hope) that perhaps it

might be able to take the rough edges off of the conduct of

a given war… perhaps even to the point of resolving the war

in an end state that the people of both sides can approve

of. But, if this new “diplomatic technology” proves unable

to win the war, then the combatants had better hope that

their “other technologies” are up to the task… or else one

side or the other will find itself in the position of the

Third Reich at the end of WWII.

All in all then, technology both provides and is the chief

source of military advancement, i.e. the advancement of

warfare. And yes, we include diplomacy and politics within

the term “military.” Technology impels changes in warfare

more than any other factor, but it does not determine

warfare. Underneath it all, warfare is impacted and

greatly enabled by technology, but without technology

warfare will continue to exist. The reason is that what we

commonly refer to as the “principles of war” exist

regardless of whether technology evolves or doesn’t… or for

that matter even exists, and in the end it’s the principles

of war that determine warfare. What do we mean by the

principles of war?

In our case the term principles of war refers to the body of

knowledge that a commander needs to know to conduct warfare.

Strategy and tactics are included here, as are those

elements that comprise a commander’s understanding of how to

wage warfare. Among these are included the concepts of

friction, the fog of war, chance, violence, intelligence,

use of terrain, the element of surprise, maneuver, maximum

advantage, planning, critical mass, economy of force,

intelligence and communication security, concentration of

force, overwhelming force, convergent attacks, command and

control, unity of command, and much, much more. From this we

can see that technology defines warfare, but it does not

determine how it is fought. It presides in warfare, but it

does not rule warfare.

So what does rule warfare and determine the outcome of war?

For that answer, we are afraid you will have to come back

next month when we continue our discussion with the Effect

of Technology on Human Agency. Clearly, from this little

hint you can see that in our view Human Agency, brought to

bear on warfare, determines both the sate of and outcome of

war. How well it does this is in great measure determined by

how well Human Agency utilizes the emerging technologies at

its disposal to modify and implement a more effective mode

of warfare

Next Month: Human Agency And Technology Create Winning Warfare

- - - Epilogue - - -

As Raphael demonstrated in 1509, Causal Power is intrinsic to “Prime Mover”

status. In the world we live in today, having Causal Power is an ontological

feature of being human. Restating this, one could say that in many cases

human beings hold Causal Power and therefore are able to exercise it in ways

able to change the existing world. One such way is by acting on technology

to become its Prime Mover. Much as early believers in 1509 thought God did

when setting the universe first in place and then in motion, people today

use Human Agency as the Prime Mover force to leverage technology to alter

the heavens. Not by filling them with stars, but with society-altering

armament.

Human Agency, acting on technology, allows the creation of new forms of

warfare, which have the capability of affecting and altering the end

condition of war.

Adding to this theory of critical realism is the opposing axiom that

regardless of the number of society altering arms one set of Prime Mover's

can place in the heavens, other Prime Movers will be able to leverage

technology to defeat their utility... if, that is, they understand that

technology shapes warfare, and they have used every mode of emerging

technology that they can get their hands on to open as many doors to Human

Agency as possible.

With this in mind, it makes one wonder: how much wisdom is there in reducing

the size of a nation's nuclear arsenal, or shuttering its missile defense

shield research, merely to make the rest of the world feel better?

Click to read the next two articles:

Article I

Article III

Have a comment on this article? Send it

to us. If you are a member of the Association we will

gladly publish it.

If you are not, well, it only costs

$30.00 a year to become a member and have your views heard...

and because

we are a fully compliant non-profit organization, your payment is tax

deductable.